The struggle to provide power to all

Two billion people lack reliable access to electricity. One fifth of the world's schools, hospitals and homes are often in the dark. How can we provide everyone with access without hastening climate change?

In the fall of 2015, Andrew Mambondiyani stood on a residential street in Mutare, Zimbabwe’s fourth largest city, on the country’s eastern border. He had just spoken to resident Priscilla Mazanga. “Cooking is now a nightmare,” she told him. With no other access to energy, she cooked for her children over fire by burning discarded plastic.

Mambondiyani, a journalist for The Zimbabwean, was on assignment as part of Power Struggle, a collaboration of journalists from around the world. His task as a Power Struggle fellow? To document how people were grappling with one of the worst droughts in his country’s history and how the drought was affecting people’s access to energy.

For the past six months, Discourse Media, an independent journalism organization, collaborated with nine journalists from the Inter Press Service, SciDev, the Zimbabwean, the Independent (Bangladesh), Al Jazeera, Thomson Reuters Foundation, Republica English Daily (Nepal), the Tyee (Canada) and TVOntario. Together, these journalists investigated how energy poverty affects people in their regions, how efforts to provide universal energy access are impacted by global systemic issues such as climate change and what solutions exist. (Learn more about the project here.)

In Mutare, Mambondiyani learned that the drought led to the death of tens of thousands of cattle. In desperate attempts to grow much-needed food, officials diverted water from small hydro power stations to irrigation. In December, water levels at the Kariba Dam — the world’s largest dam and power supplier to most of Zimbabwe and parts of Zambia — depleted to such low levels that power outages hit the entire country. Some lasted up to 20 hours.

Within two months, President Mugabe would declare a state of disaster in rural areas.

Zimbabwe’s current struggle captured the issue that motivated Mambondiyani to join the Power Struggle collaboration: the tension between climate change and the need to provide basic energy to all. “You interview a person who is starving, but you don’t have anything to give them,” recalls Mambondiyani, after speaking with a man who hadn’t eaten a proper meal for almost four days. “I’m going to write this story, but at the end of the day, is something being done for these people?”

Mambondiyani decided to look for answers by attending COP 21, the 2015 United Nations Paris Climate Conference held in December.

Starvation in Africa is often the focus of international aid campaigns, but a lack of energy access is rarely presented as a crippling challenge, despite the fact that these issues are interconnected. At COP 21, the world’s leaders batted around ideas about both starvation and energy access by addressing a persisting tension between those who have power and those who do not: Who has the right to burn carbon?

The world’s wealthiest countries relied on fossil fuels as they rose to power, while the world’s poorest countries are bearing the brunt of climate change. 1.2 billion people worldwide — about the population of China — live without access to electricity for services like heat, lighting and powering basic appliances. Another one billion have only intermittent access. It’s these deep, persistent equity issues that prove a major challenge for delegates at these conferences.

In 2007, the average Canadian household was consuming 11,000 kWh per year, while the average Indian household consumed 450 kWh.

Mambondiyani knew about the ties between poverty, access to clean cooking fuel, reliable power and climate change. His experience at home taught him that access to a reliable power grid meant his country would be more resilient to natural disasters. He was also aware that climate change projections meant the frequency and intensity of droughts are projected to worsen.

Get Involved

We’d love to hear your story. How are you impacted by the issues we’re reporting on? What solutions do you see? Who is inspiring you? Get in touch.

So when Mambondiyani arrived in Paris, he was eager to see what solutions the world’s leaders would offer. But he quickly became skeptical. To him, it seemed that politicians were arguing over semantics; contractual language and legal jargon almost derailed the international agreement to limit carbon emissions.

“While they are haggling … people are dying of floods, people are dying of hunger,” Mambondiyani recalls. “Our policymakers, do they really know what is happening on the ground?”

What does it mean to have access to energy?

Major international governing bodies agree that electricity fundamentally transforms people’s lives. The United Nations declared 2012 the International Year of Sustainable Energy for All under the premise that energy access is tied to the most basic human needs like adequate health care, food and education and that it underpins the world’s ability to meet global development priorities. The World Bank contends that energy access is essential to reducing world-wide poverty. The International Energy Agency, a collective of 29 OECD countries, argues that energy services are crucial to human well-being.

In simpler terms, it’s not just having electricity that matters. It’s what people can do with that power. And the transformative changes that electricity can enable, range from the most basic day-to-day activities to systemic services like health care and education.

For almost three billion people, access to clean cooking fuels means they not only save hours collecting fuel, they also don’t have to inhale fumes from burning wood, charcoal or animal dung. The World Health Organization reports the resulting indoor air pollution accounts for half of all deaths of children under the age of five — more than for malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS combined.

For nearly half of all health facility workers in India, access to power means lights in emergency treatment rooms, refrigeration for storing vaccines and sterilizing medical supplies.

For high-school students in Guinea, access to electricity means they don’t have to crowd into parking lots at the G’bessi International Airport to huddle under the only source of reliable light.

But while global leaders recognize the connection between access to energy and basic human needs, they are simultaneously trying to change how energy is used in order to meet climate change goals. That’s why energy access is at the core of international development negotiations like COP 21 and gets to the heart of the equity issues Andrew Mamboniyani encountered throughout his reporting.

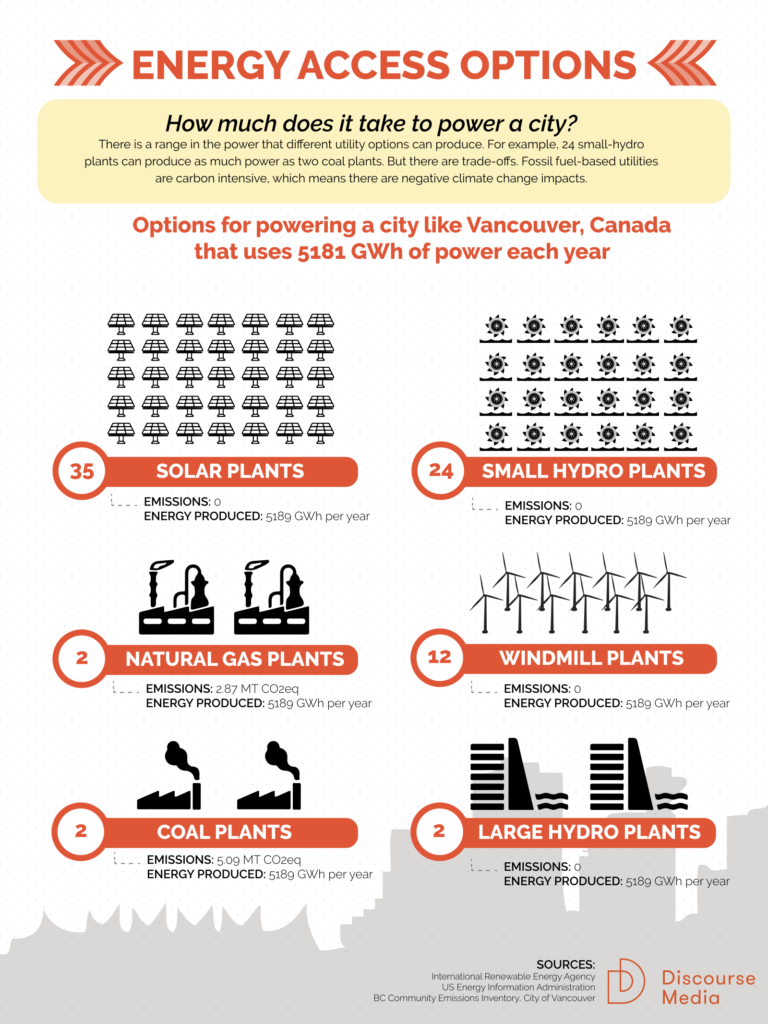

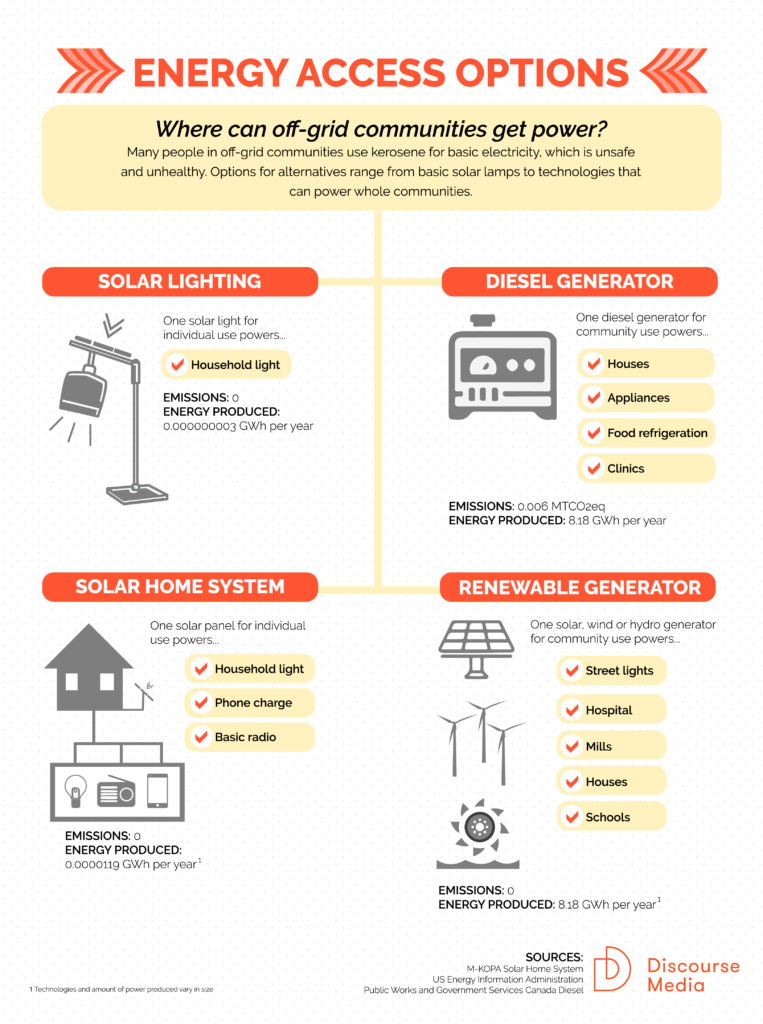

So, what potential solutions exist for energy access that also take climate change and other social and environmental issues into account?

This is the question journalists from around the world collaboratively investigated in Power Struggle. Together, their stories shed light on how different countries around the world are grappling with access to energy in a time of climate change and what it means for their future.

Elias Ntungwe Ngalame reports: How solar energy is helping Cameroon tackle poverty

Andrew Mambondiyani reports: In Zimbabwe, a struggle between climate change and energy poverty

Deepak Adhikari reports: Can Nepal defeat its deepening energy crisis?

Felix Gaedtke reports: In Transylvania, energy poverty persists in the developed world

Mike Ives reports: Why the South Pacific island Kiribati is making a big bet on solar

Fabíola Ortiz reports: Will a geothermal experiment in Costa Rica and Mexico overcome the industry’s dark past?

Faisal Mahmud reports: A solar revolution is bringing light and opportunity to the Bangladeshi countryside

Christopher Pollon reports: One northern Canadian town’s four-decade battle to ditch diesel

Eric Bombicino reports: Why a northern Canadian community’s hopes for the future rest on one power line

What themes and global issues emerged from these stories?

Nelly Bouevitch reports: Can we provide energy to all without hastening climate change?

The new business case for providing electricity to the world’s poorest

The stories featured here are just the first step.

Discourse Media plans to stick with the issue. We are purposefully participating in the conversation both online and offline. We are producing accessible data and research to help communities move forward. We are working to ensure our reporting ends up in the hands of those best positioned to create change and hold those in positions of power accountable for their promises.

This is where you come in. We want to hear how energy access affects your life. What stories have we missed? What solutions do you see? Who is inspiring you? Get in touch.