In Zimbabwe, a struggle between climate change and energy poverty

Zimbabwe is a microcosm for the entire sub-Saharan African region, where climate change and El Niño-induced droughts are driving a crisis of energy poverty that is stunting public health, economic development, and the hopes of millions to rise out of pove

ZIMBABWE

- Population: 14.15 million people

- Electrification rate: 40.00%

- Renewable energy consumption: 75.60%

- Access to non-solid fuel: 29.65%

Source: World Bank

MUTARE, ZIMBABWE — Priscilla Mazanga coughs as she stares expressionlessly into a small crackling fire in her makeshift kitchen.

“I use firewood for cooking during power outages,” says the mother of three. “Cooking is now a nightmare.”

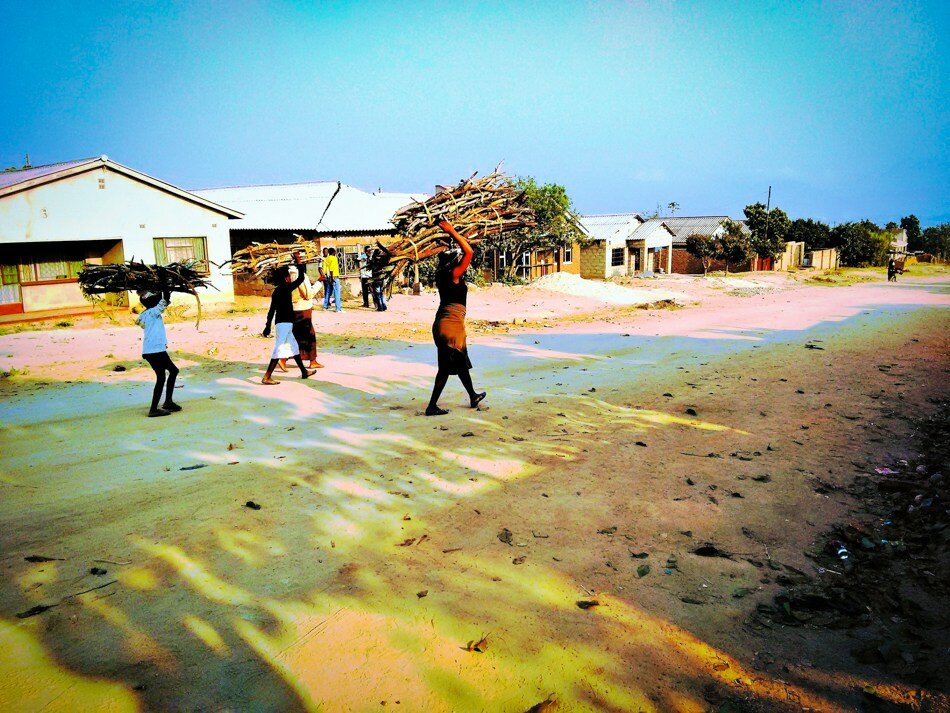

Mazanga, like many others in rural and urban Zimbabwe, now depends on wood for preparing meals during frequent electricity outages, which have become a fact of life here since ongoing droughts through 2014 and 2015 parched the rivers that supply most of the country’s electricity. At the height of electricity shortages last December, some areas of the country were without electricity for up to 20 hours a day.

Under such conditions, people turn to alternatives like firewood (or worse) to meet their daily energy needs. Mazanga, who ekes out a living selling small wares on the streets of Zimbabwe’s eastern border city of Mutare, admits she has resorted to using dirty plastic to make her cooking fires. “Life is really tough. I finish my work late in the night and when there is no electricity I have to make a fire and cook for my children.”

Fears are growing in Zimbabwe that the rising number of people resorting to primitive fuels will result in a spike of deaths related to bad household air. Exposure to indoor air pollution from cooking is the fourth leading risk factor for disease across the developing world, exceeding mortality associated with malaria and tuberculosis. According to the World Health Organization, in 2012, up to 4.3 million people across the developing world die each year from household air pollution — including from strokes, heart disease and more than half of all pneumonia deaths in children under five. Much of this death toll can be prevented with better access to clean energy.

In Zimbabwe, up until recently, much of that clean energy came from hydro power.

Inside an African hydro crisis

In 2011 hydro accounted for about 60 per cent of Zimbabwe’s total installed electrical capacityTotal installed electrical capacity is the maximum electric output that a system is designed to produce. According to the US Energy Information Administration, Zimbabwe had a total electricity installed capacity of 2.0 gigawatts in 2012., but there are dire challenges on the horizon. A drop in water levels at the Kariba Dam on the Zambezi River in north Zimbabwe (and many smaller hydro facilities across the country) has been attributed to the effects of climate change and El Niño, sparking a debate about the country’s dependence on hydroelectricity generation.

CLIMATE CHANGE VS EL NINO

El Niño is a recurring natural phenomenon that’s triggered by warming surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, on an irregular basis, usually every two to seven years. As warming oceans are among the consequences of climate change, it’s likely we’ll see an increased frequency of extreme El Niño events. In this way, climate change is “loading the dice” for more extreme weather, including El Niño.

Experts have linked the 2015-16 drought in Zimbabwe and other countries in southern Africa to the El Niño weather phenomenon — which they say has been intensified by climate change. Zimbabwe’s drought during the 2014-15 farming season was not induced by El Niño, but solely by climate change.

By the end of January 2016, the Kariba dam was generating at roughly half its capacity (less than 400 megawatts instead of the installed capacity of 750 MW). This year alone, water levels have declined to 12 per cent of its full capacity.

That’s a serious problem because the country needs 2,200 MW at peak consumption to meet demand, but is currently only capable of generating about half of that (around 1,300 MW). By January this year, Zimbabwe was importing 300 MW from South Africa, which resulted in an improvement in electricity supply. But the Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority is now planning to increase electricity tariffs by 49 per cent from US 9.86 cents to 14.69 cents per kilowatt hour. (The power utility said the hike, still in the planning stages, will be necessary because Zimbabwe is forced to pay much higher prices for the imported electricity than it is charging to local consumers.)

Many other sub-Saharan African countries are facing similar dilemmas. “Most of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa depend on hydro power for their electricity needs,” wrote Ugandan energy expert Barnabas Nawangwe in a news release from The Competitiveness Institute. “The fall in levels of lakes and drying up of rivers has meant that the generation capacity has fallen drastically. Many countries have been forced to purchase and operate [fossil fuel] thermal generators, which has led to an escalation of electricity tariffs,” Nawangwe said.

Nawangwe warned that climate change has made an already bad situation for competitiveness of African businesses even worse.

Stark choices: irrigation or electricity?

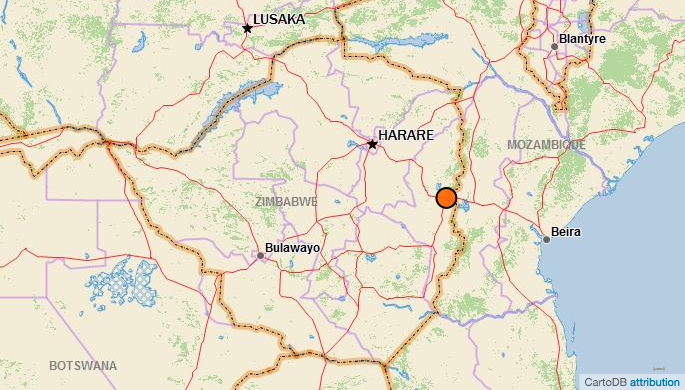

As the droughts bite deeper, privately-owned small hydro power plants in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands have been hard hit by water shortages. One such hydro power station is Chipendeke, located about 70 kilometres south of the eastern city of Mutare near the Mozambique border.The Chipendeke and the neighbouring Himalaya hydropower project are part of a sustainable energy initiative spearheaded by Hivos, Zimbabwe Regional Environment Organization, Practical Action and the Zimbabwe Energy Council.

On a late January visit to the 25 kilowatt capacity Chipendeke hydro station, up Himalaya Mountain in the Eastern Highlands, the water levels on the Chitora River (which supplies water to the hydro facility) were so low that electricity generation had been temporarily suspended. A small building that houses the plant’s power turbines was under lock and key; the generator was switched off.

Phillip Muwungani, a resident of the Chipendeke village, , confirmed that the hydro station had been shut down on Jan. 27 due to low river water levels. “We use the same water for irrigation and electricity power generation,” he said. “We are using the little water available to irrigate our crops.”

Another villager in the same area, Joseph Nakai, said the power outage had affected a local school, clinic and business centre. “We hope things will improve if we receive some rain. The clinic needs electricity to preserve medicines,” he said.

Elijah Ngwarati, who resides in the same area, said the future of hydro power in this area does not look bright. “The future is gloomy. We hope the rains will come soon.”

The stunting human impact of energy poverty

While energy demand continues to rise in Zimbabwe, the International Energy Agency estimates that 40 per cent of the population (this is a national average) has access to electricity, dropping to just 21 per cent in rural areas. This shortfall in energy has a debilitating effect on virtually all sectors of the economy.

“Energy for lighting is poor in households, schools and health institutions,” said Amy Wickham, a Climate Change Officer with UNICEF Zimbabwe. “Poor quality light affects studying period for children especially during the evening, contributing to poor academic performance. It has been reported that some children have been forced to burn old rubber slippers to get lighting,” she said.

Wickham said a lack of funds and limited available technology is limiting access to sustainable energy in remote rural areas. She added that a transition toward reliable energy for cooking is a complex issue, because cooking cannot be viewed in isolation from lack of access to basic health, education and information services.

The path forward?

Gloria Magombo, CEO at the Zimbabwe Energy Regulatory Authority, said the country needs at least US$9 billion to increase national power generation to a target amount of 5,000 MW by 2030.

It is now the government’s goal to produce 300 MW from renewable energy sources by 2018; with international help, the country hopes to push clean energy research and financing forward.

Projects to be complete by 2018 include the Hwange Thermal Power Station extension (coal powered), small thermal repowering projects (plants used when there is high electricity demand or during a power outage), Kariba South Power Station extension (hydro), the Gairezi hydroelectric plant and more solar power plants not yet started.

Within two years Zimbabwe hopes to generate about 20 per cent of its electricity from solar, although this is not without challenges.Within two years Zimbabwe hopes to generate about 20 per cent of its electricity from solar, although this is not without challenges. “The problem is that [solar] storage is very costly and has a limited life span at present,” said economist and elected official for Bulawayo South Eddie Cross. “Therefore we will still have to rely on coal for our base loadThe power required to satisfy the minimum demand and perhaps gas.”

Cross added that, despite droughts, hydro remains the least costly option. The Kariba dam produces power at US 1.5 cents a kilowatt hour, while coal costs eight to 12 cents and solar is 20 to 30 cents. “Providing we use hydro as a peak supplier and not as base load, we should be okay at 85 per cent of the water in the Zambezi River (Kariba Dam).”

A wider African energy crisis

Zimbabwe is not alone in facing an energy crisis driven by climate change-induced droughts.

Neighbouring Zambia and Tanzania have been particularly affected by what is a regional energy crisis. A recent article from South Africa’s Independent Online Business reported that the 2015 drought left the three countries generating far below their capacity because of low water levels in the catchment areas feeding hydro plants.

Tanzania was forced to shut down all of its hydroelectric generation in October 2015 due to fears that the generator turbines would be damaged by air entering the systems. The country has since launched a US$1.33-billion project to pipe natural gas to the city of Dar es Salaam to alleviate power shortages in the city.

Zambia is by far the most dependent on hydro, generating 90 per cent of its electricity from three hydroelectric power plants at Kariba (both Zimbabwe and Zambia use this dam for electricity), Kafue Gorge and Victoria Falls. (Tanzania receives about 60 per cent of their electricity supply from hydro.) In late January of this year, Zambia’s power utility ZESCO Limited was forced to cut electricity generation to a quarter of capacity at the Kariba hydropower plant due to low water levels. To date, the power crisis has also affected the mining industry operating in the country.

“We have a power deficit of 630 MW as of January 2016,” said ZESCO spokesperson Henry Kapata in a recent interview. “We expect this to reduce to below 160 [MW] by August 2016 as mitigation measures are put in place.”

These mitigation measures include adding power imports and establishing a 300 MW coal-fired plant due to start output in June. This adds to the reliance on coal for electricity, which as of this writing stands at about 40 per cent.

Climate change impact on electricity a global issue

Climate change impacts on rivers and streams may substantially reduce electricity production capacity globally, according to a recent studyWorldwide Electricity Production Vulnerable to Climate and Water Resource Change International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Austria and Wageningen University, Netherlands http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nclimate2903.html, and it’s not just hydro generation that could be threatened.

In a wake-up call to the world, the researchers called for a greater focus on climate change adaptation efforts in order to maintain future energy security. “Hydropower plants and thermoelectric power plants—whether nuclear, fossil-, and biomass-fueled plants converting heat to electricity—all rely on fresh water from rivers and streams,” wrote lead International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) researcher Michelle van Vliet. “These power-generating technologies strongly depend on water availability, and water temperature for cooling plays in addition a critical role for thermoelectric power generation.”

The researchers crunched data from 24,515 hydro and 1,427 thermoelectric plants around the world, and found that climate change impacts, and associated changes in water resources, could lead to reductions in electricity production capacity for more than 60 per cent of the power plants worldwide from 2040-69. According to the study, hydro power and thermoelectric power currently contribute to 98 per cent of electricity production worldwide.

“This is the first study of its kind to examine the linkages between climate change, water resources, and electricity production on a global scale. We clearly show that [thermoelectric] power plants are not only causing climate change, but they might also be affected in major ways by climate,” said IIASA Energy Program Director and study co-author Keywan Riahi.

The study identified southern Africa, the United States, southern South America, central and southern Europe, Southeast Asia and south Australia as particularly vulnerable regions because declines in mean annual stream flow are projected, combined with large increases in water temperature under changing climate.

“In order to sustain water and energy security in the next decades, the electricity focus will need to increase on climate change adaptation in addition to mitigation.”

WHAT STORIES ARE WE MISSING?

We welcome your ideas. Get in touch.