Pacific Northwest LNG court battle: 'At jeopardy is our whole tribal system'

Interpreting Indigenous law in a western court system is like 'trying to put a circle in a square,' says the Gitwilgyoots Tribe, one of two governing systems for the Coast Tsimshian people.

A non-Indigenous federal judge will decide how one northern B.C. First Nation will govern its territory, after a major liquefied natural gas project caused deep divisions in the community.

While many First Nations challenge resource development projects in court, this case is different. It's magnified an internal dispute within the community over who has authority to speak for the land. The outcome could have a big impact on how consultation with First Nations happens — and who gets a seat at the table.

The case involves the Coast Tsimshian, near Prince Rupert. Two elected band councils there, the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla, support the $36-billion Pacific Northwest LNG (PNW LNG) project. They’ve signed benefit agreements giving their consent for development. But local hereditary leaders of the Gitwilgyoots Tribe, who have their own traditional system of governance, claim they weren't consulted and say it’s not the band’s decision to make. So, they’re in court trying to have the federal government’s approval of the project overturned. Late last week, the arguing sides gathered at the Vancouver federal courthouse.

Don Wesley, also known as Yahaan, filed the application on behalf of the tribe last October. Then in March, both the Lax Kw’alaams Band and PNW LNG filed a motion to have Wesley’s case dismissed. Last week, the band’s lawyers tried to justify why the case should be thrown out. The lawyers spent most of the two days in court trying to discredit Wesley as leader of the Gitwilgyoots, arguing that his tribe members are actually represented by the Lax Kw’alaams and Metlakatla.

“The question is really: Who holds Aboriginal title? Who speaks for the collective?” Cynthia Callison, a lawyer from the Tahltan Nation who specializes in constitutional law, tells me in a phone interview. “I’m surprised that the band is going against the hereditary chief system. It’s very strong.”

Justice Robert Barnes, the judge assigned to the case, must now decide who can represent the broader Coast Tsimshian people on this project: the bands or the tribe. He's expected to make a decision in several weeks, determining if Wesley’s case against Ottawa’s approval of the project can move forward.

Two systems in conflict

The Tsimshian, like many First Nations, have two governing systems. One is a hereditary governance system that existed before European contact. It includes nine ancient tribes, including the Gitwilgyoots, each with a Sm’oogyit, or head chief. A Sm’oogyit name, such as Yahaan, is passed down from generation to generation. Whoever holds the name at any given time has a cultural obligation to protect the traditional territory associated with it.

In the case of the name Yahaan, that obligation includes Lelu Island, which is the proposed location of the PNW LNG project. According to court documents filed by the Gitwilgyoots, Wesley’s responsibilities as a hereditary chief “are more in the nature of a multi-generational, fiduciary duty than subject to short-term political decision-making.”

But leaders of the elected band council system say it’s the bands’ job to protect the rights of Tsimshian people in modern times. Court documents filed by the Lax Kw’alaams point out that “the Gitwilgyoots Tribe has no staff, tax base or other source of income, or even a bank account.” The band argues that it manages economic needs, whereas the tribe oversees cultural responsibilities.

Administered under the Indian Act, bands receive funding from the federal government, and report to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. It’s a colonial system that the federal government imposed on First Nations. Over time, however, the band system has replaced the traditional system in many places throughout B.C., Callison explains.

“You have a bit of a push and pull. In some communities, the Indian band does represent all the people with respect to [Aboriginal] rights. I’d say in British Columbia, that’s probably two-thirds [of First Nations],” she says. Adding that the remaining third, like Tahltans, Haida and other people, saw way back when that it’s better to have governement systems that aren't strictly hereditary or Indian Act.

Awaiting judgement

Lawyers for both Tsimshian bands and PNW LNG cited affidavits from Gitwilgyoots members who don’t support Wesley’s actions. There’s also uncertainty around how many members are in the tribe (around 400 to 450), as well as an internal dispute over whether Wesley is actually its head chief.

Barnes repeated multiple times during the hearings that he can’t resolve internal tribal matters, showing how difficult it is to interpret Indigenous law in a western court system. He’s expected to announce his decision on Wesley’s standing in several weeks.

Unlike bands that hold elections to form a governing council, the chieftainship Wesley claims is hereditary. Rather than a one-vote-per-person system, the tribe makes decisions much like how a family would, the Gitwilgyoots lawyer explained. As a result, proving the legitimacy of tribal business is difficult because it’s hard to show that there was consensus.

Barnes said he recognizes that Tsimshian tribes are unique entities with leaders, but asked for evidence that proves Wesley can take a firm position on the PNW LNG project without the clear support of his tribe members.

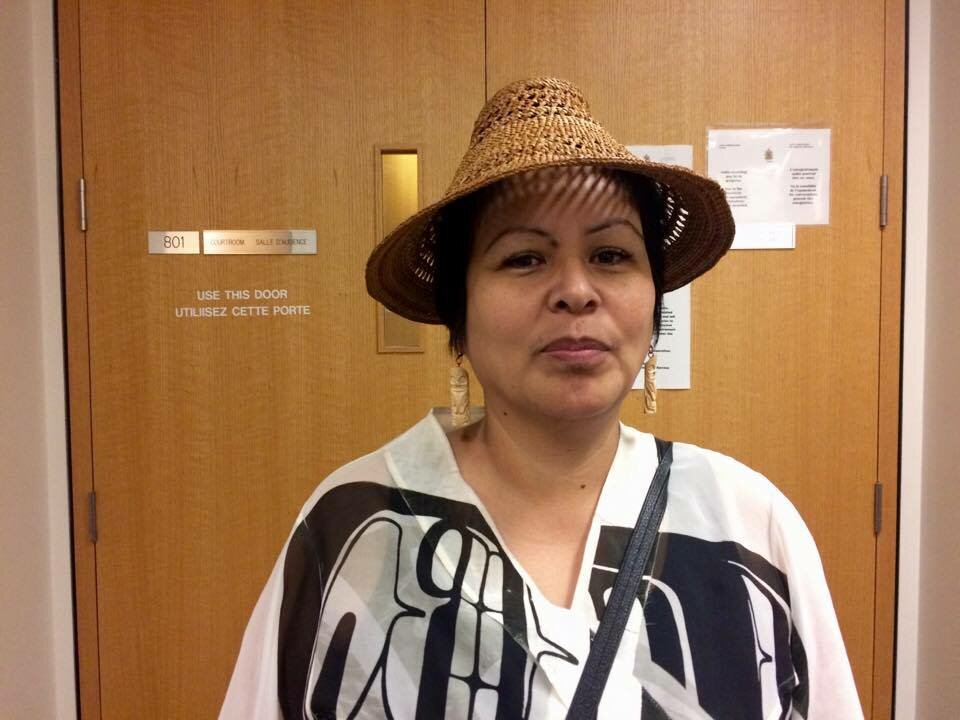

“They don’t have an understanding of the hereditary system, and they are looking at it through colonial eyes,” Gitwilgyoots member Christine Smith-Martin, who supports Wesley as head chief, tells me outside the courtroom during a break. “They’re kind of trying to put a circle in a square, and it’s just not fitting.”

Watching closely

Barnes’ decision could have broad implications for other First Nations launching similar court challenges against PNW LNG. “I’m very concerned that the bands are going to get more recognition than the hereditary structure,” says Richard Wright, spokesperson for the Luutkudziiwus, a hereditary group similar to the Gitwilgyoots that belongs to the Gitxsan Nation in B.C.’s northern interior.

“We’re very concerned that this may have a negative impact on our court case that is yet to come,” he adds. “I can see one of the arguments being brought towards us is: Who owns the collective rights for the Gitxsan?”

The Gitxsan were plaintiffs in the 1997 Delgamuukw decision that established a test to prove Aboriginal title over traditional territory. In Delgamuukw, Canada’s Supreme Court also recognized Aboriginal title as being a collective right, belonging to all members of a First Nation. But the issue of who is the proper rights-holder was not determined.

In the 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision, the most recent landmark judgement on Aboriginal title, Canada’s Supreme Court upheld the B.C. Court of Appeal’s conclusion that the Tsilhqot’in Nation as a collective is the proper rights-holder. But who speaks for the collective is decided within the collective itself.

Callison says the onus is on Wesley to prove he has his tribe’s support, and that the tribal system is how Tsimshian people want to be governed. “I’m assuming that this is a strong hereditary system where they still potlatch, [and] where the majority of the people still believe in their traditional system,” she tells me. “But I don’t know about the internal politics and why the band thinks that they have the right to approve resource development.”

Long road ahead

Should Barnes side with Wesley, the judicial review of the federal government’s approval of the PNW LNG project will begin. But even if Barnes sides with the bands, Wesley can still appeal.

“What I feel is at jeopardy is our whole tribal system,” Gitwilgyoots spokesperson Murray Smith tells me. “To try and minimize us and say we have no rights on your own traditional sacred lands — you can’t do that.”

Lax Kw’alaams Mayor John Helin was sitting silently in the courtroom during last week's hearings. He declined to comment.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that in the 1997 Delgamuukw decision, Canada’s Supreme Court recognized the tribal system as the proper rights-holder. In fact, the issue of who held the rights was not determined. This story also incorrectly stated that in the 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision, the Supreme Court recognized Indian Act bands. In fact, the courts recognized the Tsilhqot’in Nation as a collective as the proper rights-holder. (June 21, 2017)