One man’s trash: Could garbage solve Nigeria’s energy crisis?

Why an innovative project to turn food waste into power has been abandoned, leaving millions of Nigerians in the dark.

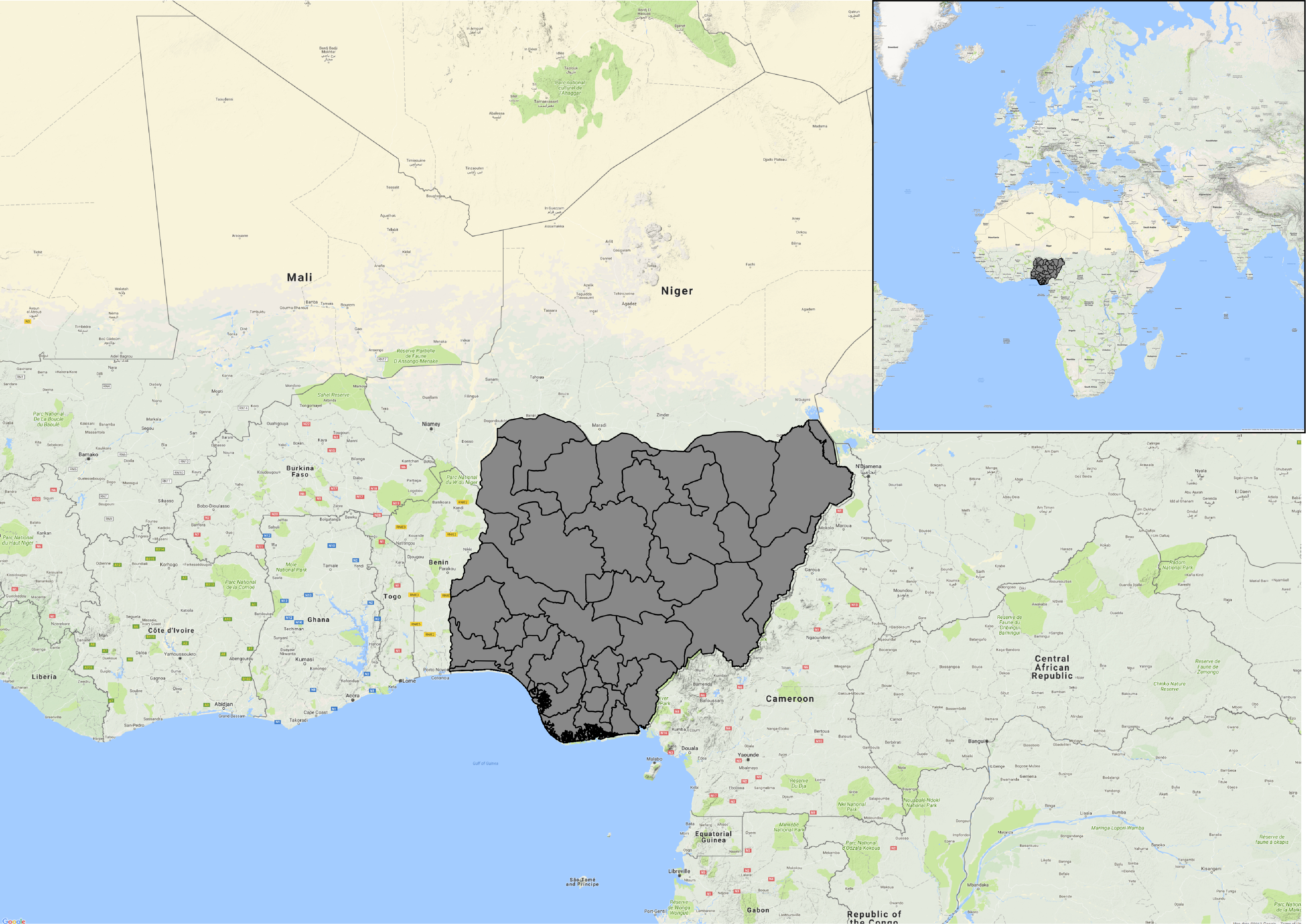

NIGERIA

- Population: 185,989,640 people

- Access to electricity: 57.7%

- Renewable energy consumption: 87.27%

Source: World Bank

Two kids run across the road shouting, “Thief! Thief!” as a big rat races away into a nearby hole for refuge. The rat was trying to snack on some well ripened banana for lunch.

It has rained here and the drains are clogged with waste. The water pools on the road and occupies potholes that dot the stretch of the thoroughfare leading to Lagos’s famous Ikosi fruit market.

One of the largest of its kind in the Nigerian city, the market is a popular spot for trading fruits and vegetables like pineapples, bananas and plantains. But here, like most parts of the country, there is rarely a steady power supply — according to the World Bank, 75 million Nigerians don’t have access to electricity.

“The light issue is a big one here. When there is no light, we have no choice but to close early, especially when we are witnessing shorter days and longer nights,” says Ajose Abosede, a trader in the market.

Lagos, the largest city in Africa, has a population of more than 20 million people, occupies almost 1,000 square kilometres and generates more than 13,000 tonnes of garbage a day. Fifty per cent is organic waste, says Lanre Gbajulaye of the Lagos State Waste Management Authority (LAWMA).

A huge chunk of that waste comes from more than 30 markets — and therein lies surprising potential. Experts believe that Lagos can be energy sufficient if it can tap into the latent power of its organic garbage, but it’s taking longer than they hoped.

Wasted potential

Disturbed by the increasing menace of waste in the city, in 2013, Lagos state government partnered with Midori Environmental Solutions (MES), a Lagos-based environmental company. The idea was to explore the possibilities of converting waste from the Ikosi fruit market, the largest in the city, into electricity.

At the time, the project was meant to be an indicator of the state’s innovative drive for solving its major energy crisis. This seemingly proactive step was applauded by local and international observers. But, four years later, the project has been seemingly abandoned and residents are still struggling to access reliable power.

“The project turned out to be a fair deal,” says Aniche Phil-Ebosie, former project developer at MES, who managed the initiative. “Before we started… we noticed that the market generates over five tonnes of fruit waste daily. Most of it is rotten or squashed due to the bad storage systems and transportation. Of the total waste generated, 5 per cent goes to the biogas plant, 45 per cent is carted away by LAWMA to landfills, and 50 per cent goes off-site and [is] composted,” says Phil-Ebosie.

“Market women were happy to provide waste for the project instead of paying to have it collected by the Lagos State Waste Management Authority.”

Phil-Ebosie explains that MES got a license from AFRICOM Technology Transfer, a German company, to build a “low-technology” facility. To generate electricity, first food leftovers are rinsed and ground into a paste. The paste is then fed into a biodigester where bacteria break it down and release biogas in the process. Once filtered, the gas can be used as fuel for a natural gas-powered generator, which produces electricity.

Aniche Phil-Ebosie, former project developer for Midori Environmental Solutions, gives a tour of the biogas facility. (Video credit: Heinrich Boll Foundation)

The facility at the market produced enough biogas to provide light for up to 50 stalls and lock-up shops. It was especially critical at night and in the early hours of the morning when trucks come in to offload fruit brought into the market from different parts of the country.

Saliu Adenekan, a banana trader in the market, thought the project was a joke.

“As old as I am, I have not seen or heard of how waste is used to generate light. I know that there must have been a way that people abroad treat and use their waste, but I have no idea we can do [the] same here in Nigeria, to say nothing of it working in Ikosi,” says Adenekan, who claims to be at the bottom of the market’s complicated leadership structure.

Adenekan was excited when contractors moved in and the facility was finally launched. But Adenekan’s excitement vanished about 18 months into the project’s lifespan when the government asked the contractor to hand it over. LAWMA took over the initiative with the idea that it would be replicated in other markets across the state.

That turned out not to be the case. Three years on, it is back to square one. The facility has stopped working and Ikosi fruit market has returned to its former condition: a community of traders, waste and pests competing for space in darkness.

High stakes of erratic power supply

Nigeria’s three-pronged energy infrastructure consists of generation companies, distribution companies (DisCos) and the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN). The country operates on a grid system where electricity generated by the power plants is sent into the national grid, transmitted by the TCN and delivered to the DisCos.

But, despite having the largest gas reserves in Africa, Nigeria still struggles to supply its power plants with adequate gas to generate electricity. This situation is worsened by the DisCos’ financial mismanagement, to say nothing of the frequent vandalism of gas pipelines in the country’s oil-rich Niger Delta by local militants fighting for resource control.

“Most of the distribution companies are owned by corrupt and wealthy people who thought there is free money to be made in the power sector."

On March 31, 2016, at exactly 12:58 p.m., Nigeria’s power grid collapsed completely with not a single megawatt of electricity generated for three hours. This was unprecedented in the country.

Aliyu Wabba, president of the Nigeria Labour Congress, says the deplorable state of the country’s power sector has stifled Nigeria’s economy. Industries have not been thriving, which in turn inhibits employment opportunities for young Nigerians.

“The economy continues to grow without jobs, bringing benefits to only a few. We demand an economy that provides jobs and other benefits,” says Wabba.

Landmark reforms in 2014 allowed private sector participation in the power sector, particularly in power generation and distribution, but there remain problems. Wabba believes the 2014 privatization drive was a major problem and needs to be revisited.

Wabba is not the only one who shares this view. Renowned economist and two-time finance minister Kalu Idika Kalu says privatization was not properly achieved, and this has made finance in the sector a major issue.

Kalu says certain crucial steps do not appear to have been considered, like ensuring that investors who bought DisCos were appropriately capitalized, or that they understood the technology of the enterprises they were to own. He believes Nigeria should have strengthened its governance structure before embarking on privatization. Experts also believe that corruption, poor leadership, bad implementation and non-adherence to policies by the government are major factors compounding the problems in the power sector.

Yemi Oke, associate professor of energy and electricity law at the University of Lagos, believes the problems in the power sector are multidimensional and largely man-made.

“Most of the distribution companies are owned by corrupt and wealthy people who thought there is free money to be made in the power sector. They borrowed money and bought the distribution companies only to say that they won’t incur the liabilities of the company,” Oke tells me during a chat in his office in Lagos.

According to Oke, the nation’s recent economic meltdown reveals that the private investors were not as technically and financially sound as they should have been before taking over the distribution companies. And when the price of oil tanked — and with it the value of the naira, Nigeria’s currency — the trouble only accumulated.

But Babatunde Raji Fashola, the minister of power, works and housing, has said that the country will not review the 2014 privatization of the power sector. This decision is intended to protect the image of Nigeria in the eyes of the international community, and present the country as a serious and stable investment destination.

Searching for solutions

As a short-term measure toward solving the electricity supply problems, the Nigerian government has opted to develop an incremental power strategy. With this strategy, observers say, the Nigerian government has shown more commitment in harnessing power from all available sources. This is where ideas like generating energy from garbage come in.

The government has resolved to generate 20 per cent of its total energy consumption from renewable resources by 2030. Nigeria has immense opportunities to generate electricity from sources such as solar, wind and biomass. The emphasis on renewable energy has already started yielding results, as the country has started witnessing huge investments in the generation of electricity from renewables.

In 2016, $2.5 billion US was committed to 14 renewable energy projects by private investors, with the intention of adding a combined 1,000 megawatts to the national grid. According to Oke, Lagos State can conveniently produce this amount of electricity from its huge amount of waste.

Oke says the government must ensure that its energy policies are clear if it wants to achieve appreciable success as soon as possible. And this is not always the case.

“For now, if you generate in excess of one megawatt, you have to sell it to the national grid even when your rural or local population doesn’t have power and there is no guarantee that the power you have generated will benefit you at the end,” Oke explained. In other words, local consumers suffer at the expense of feeding the national grid, and the energy is dispersed into the ether.

If the strategy of generating energy from multiple sources is to take shape, the Ikosi market shows both the upside and the downside.

Ajani Ojo is described as the “waste converter” by his colleagues who have come to realize the value in rubbish. “Waste is money,” Ojo quips, as he tours the dormant biogas plant in the market. He now makes a living from selling plantains and setting up low technology biogas facilities for people. He says he learned all he knows about converting waste to value from MES, the contractor who handled the Ikosi project.

Ojo wants government to resuscitate the project. “When the facility was working, waste scattered all over the market was reduced, especially around the banana section,” he says, pointing to an open field near the facility.

“Apart from that, we didn’t have to pay the waste collector money to take our waste. We gave it up for free to the facility to generate electricity for our use.”

Gbajulaye of the Lagos State Waste Management Authority says the current governor of Lagos, Akinwunmi Ambode, has started working on waste management under the Cleaner Lagos Initiative (CLI). As part of the new program, LAWMA will contract out waste disposal and become more of a regulator in the waste management sector. It’s a big job for a rapidly growing city to change the way that waste is collected and improve infrastructure like sanitation. Though the initiative is focused on making Lagos the greenest city in Africa by 2025, it doesn’t yet include generating power with city garbage.

But for Ojo, it is clear that the government should pursue this path wholeheartedly. He believes that there is a need for better appreciation and commitment to solving two problems using a simple technology.

“My eyes are now opened and government’s eyes should be wider.”

This content was produced with the support of the Access to Energy Journalism Fellowship and Discourse Media. The story was edited by Lindsay Sample and Richard Poplak, with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim and Daina Lawrence. The graphics were created by Caitlin Havlak. Discourse Media’s executive editor is Rachel Nixon.