How solar energy is helping brighten childbirth in rural Zimbabwe

Solar power installed at the Mazuru clinic in Zimbabwe is making childbirth safer and less expensive for women.

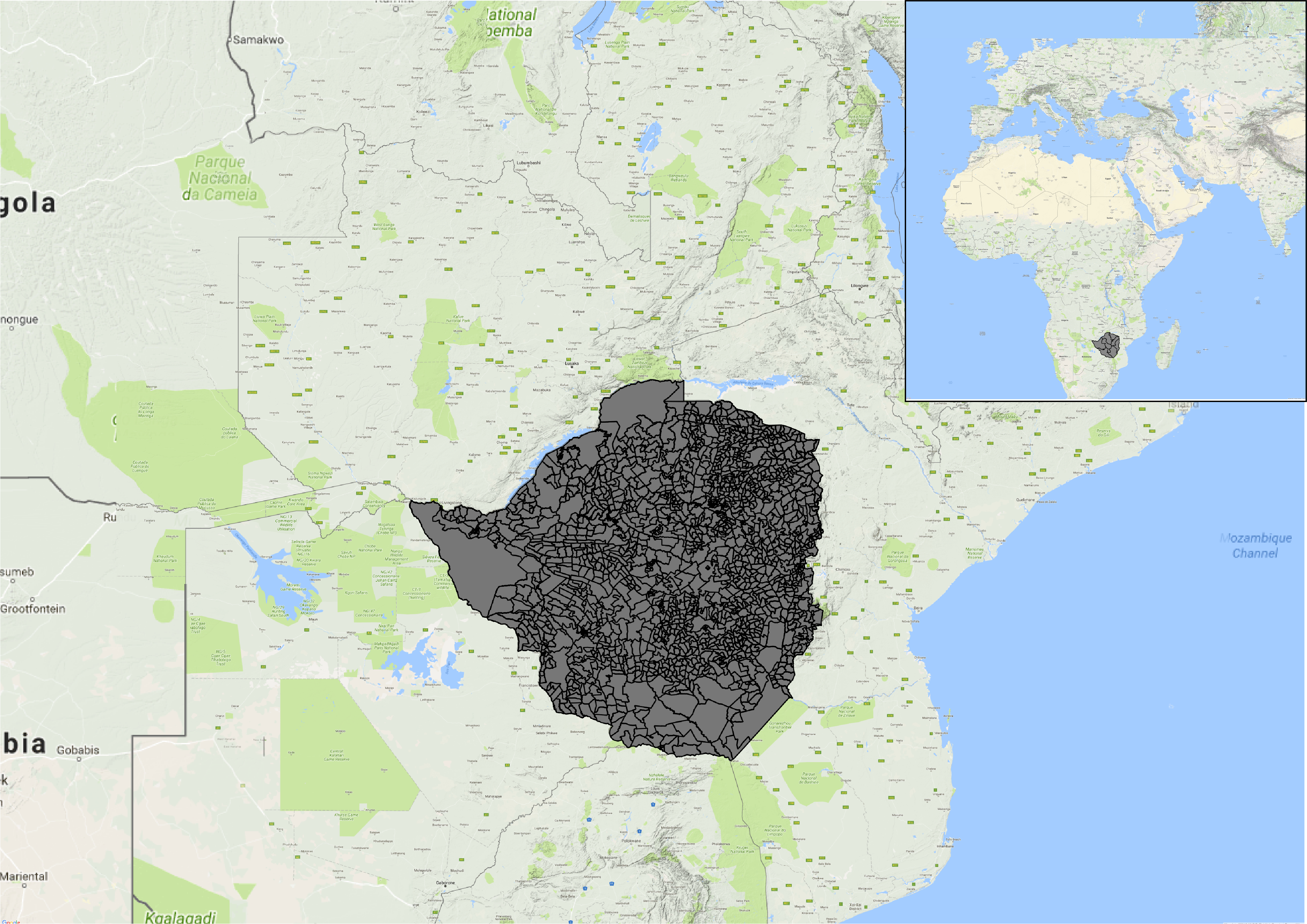

ZIMBABWE

- Population: 16,150,362 people

- Access to electricity: 32.3%

- Renewable energy consumption: 81.13%

Source: World Bank

Juliet Chasamuka, 34, was six months pregnant when I met her in the Gutu district of Masvingo, a rural community 300 kilometres south of Harare, Zimbabwe. The now mother of five has had many different experiences when giving birth.

For her first two births, as is the norm at many poor health care centres in the remote areas of this largely agrarian country, Chasamuka was expected to bring her own candles, matches and kerosene lamps. Expectant mothers are sometimes even asked to bring water for cleaning and washing during their stay at a clinic.

Buying these resources was a problem, says Chasamuka. “My husband has never been employed,” she explains. “As a family, we depend on working in other people’s fields in return for either food, money or clothes. It was therefore difficult for me to buy the required supplies.”

For her next two children, she decided to give birth at home due to the expense. “I was assisted by a village midwife, and fortunately it went well,” she says. As is common here — almost 22 per cent of women in Zimbabwe give birth without skilled health care staff present — the midwife Chasamuka used did not have formal medical training.

The situation is made worse in rural areas like Chasamuka’s where energy access is a major problem. The most recent World Bank data shows that, in Zimbabwe, 83.4 per cent of people in urban areas have access to electricity, as compared to 9.8 per cent in rural areas. This is despite the fact that 68 per cent of the country’s 16.2 million inhabitants live in rural areas. In serious need of electricity, the Mazuru clinic turned to solar energy.

What it’s like without power

The Mazuru clinic serves approximately 15 pregnant mothers every month, and supports a population of 6,700 people. Like most of Zimbabwe’s rural health clinics, Mazuru’s maternity ward has been limited in the care that staff can provide. The infant mortality rate in the country is 60 deaths per 1,000 live births, while it’s estimated that 614 mothers die for every 100,000 live births (100 times that of the rate in Canada).

“If I was using the torch on my mobile phone, I had to hold it in my gloved hand while operating, sometimes with blood on the glove,” says Ratiel Chikuvire, 52, a head nurse at Mazuru clinic. “Sometimes I held the phone with my teeth, especially when I was repairing a torn cervix or suturing perineal lacerations, since I needed direct light to enable me to carry out the process.”

But in 2012, with support from Oxfam Zimbabwe, a solar water pump was installed at the Mazuru clinic. “We installed a solar pump, a 5,000 litre water tank, and this has made life easier for not only the clinic staff and patients, but for the surrounding communities,” says Conillius Muchecheti, formerly Oxfam Zimbabwe’s Coordinator for the Rural Sustainable Energy Development (RuSED) Project.

After the water pump was installed, they still needed electricity, so in 2013, the community purchased a “solar suitcase.” It holds three strong solar-powered lights, a blood pressure gauge, a fetal scope and mobile phone charging sockets, which means expectant mothers can now attend the health centre with fewer concerns.

“There are no user fees, and no need for candles and kerosene lamps,” Chikuvire explains, adding, “now we can do birth deliveries at night with no worries about lighting.”

Following the installation of solar power at the clinic, Chikuvire says there has been a 50 per cent increase in the number of women giving birth there. Chasamuka contributed to the increase; she chose to have her fifth child at the now powered clinic. Aside from the Mazuru clinic, the RuSED project equipped four other clinics in the Gutu district with solar pumps.

Zimbabwe’s health sector leans heavily on support from development partners. The country’s 2017 budget statement reveals that the health budget is at 6.88 per cent of the overall government expenditure with about 93 per cent of that going toward salaries. This is well below the 2001 Abuja Declaration commitment — at the time, leaders from African Union countries met and pledged to set a target of allocating at least 15 per cent of their annual budget to improve the health sector. On top of this, the national health strategy indicates that, in 2012, over 40 per cent of health sector funding came from overseas development assistance.

In 2016, the African Development Bank noted that, while women and men have different energy needs linked to their gender roles, women are affected more than their male counterparts by poor access to energy.

“It’s difficult for staff to work effectively with kerosene lamps, mobile phone torches or candles to carry out operations or suture tears,” says head nurse Chikuvire, adding that smoke from kerosene lamps and candles cloud up the maternity ward, causing newborn babies and their mothers to cough.

There are over 1,400 health clinics in Zimbabwe. The Rural Electrification Agency’s (REA) public relations and marketing executive, Johannes Nyamayedenga, says that while the organization has supported the electrification of 852 rural health facilities, some 202 are still awaiting electricity. Nyamayedenga says the agency is unable to provide energy in all the rural institutions because of funding shortages. “That means these women will continue to be impacted negatively,” he says.

The move towards solar

Zimbabwe was once considered the breadbasket of southern Africa, but due to drought and political turmoil, the economy stalled in the 1990s. A structural adjustment package imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund resulted in a period of deep cuts and officially mandated austerity. A government adopted program of radical land reform, which involved kicking white farmers off their fields, has led to international sanctions and created economic chaos.

“Zimbabwe is a country with huge renewable energy resource potential, yet their exploitation to address energy poverty is negligible due to prevailing economic challenges,” according to Sustainable Energy for All. They are likely referring to the political and economic chaos that has become normalized under President Robert Mugabe’s leadership.

What has all of this amounted to in practical terms? In 2017, the Africa-EU Renewable Energy Cooperation said electricity supply had dropped to less than half of what the country used between 2015 and 2016. The crisis was mostly the result of declining water levels at the Kariba hydropower plant and technical faults at the coal-fired Hwange power station.

In February 2016, Lake Kariba was operating at 11 per cent of its full capacity, the lowest in 20 years. Maintenance and repairs led to extensive “load shedding” — meaning rolling blackouts — causing regular power interruptions, lasting up to 18 hours, across Zimbabwe.

Despite government efforts to expand existing facilities, energy experts say there is a need to develop decentralized energy systems based on renewable energy sources, mainly in rural areas. When it comes to things like providing solar energy at health clinics, the REA’s Johannes Nyamayedenga says the funding the agency receives from the government isn’t enough. He urges rural communities to come up with ways to maintain and repair equipment that they have installed, instead of depending on the REA to fix everything.

Kudzi Chitiva, solar energy expert and director of the Zimbabwean company Natfort Energy Efficiency, says solar is notoriously expensive and requires constant maintenance. There is poor regulatory policy and little oversight, according to Chitiva. “An anything-goes mentality means that far too many substandard products are installed,” he says.

In the case of the Mazuru clinic, the solar pump was purchased with Oxfam’s support. The organization also helped the clinic set up a community energy fund (CEF), financed in part by selling solar lanterns. The fund is meant to ensure the long-term sustainability of the project and put communities in charge of decision making about their energy needs. The community then used the CEF to buy a $2,800 solar suitcase for the maternity unit. To support the CEF, community members contribute between 50 cents and a dollar every month.

Juliet Chasamuka insists that paying a dollar towards solar energy system repairs and maintenance is better than having to pay for the supplies needed to give birth without electricity. “If we don’t,” she says, “the burden falls heavily on us as women.”

Though Chasamuka and other women who live far away from the community still grapple with walking the long distance to the clinic, the challenge of bearing significant costs when giving birth is over — at least for now.

This content was produced with the support of the Access to Energy Journalism Fellowship and Discourse Media. The piece was edited by Lindsay Sample and Richard Poplak, with fact-checking and copy editing by Jonathan von Ofenheim and Daina Lawrence. The graphics were created by Caitlin Havlak and the videos were edited by Andrea Josic. Discourse Media’s executive editor is Rachel Nixon.