Lip service or endgame: Trans Mountain Expansion Project gets Indigenous oversight committee

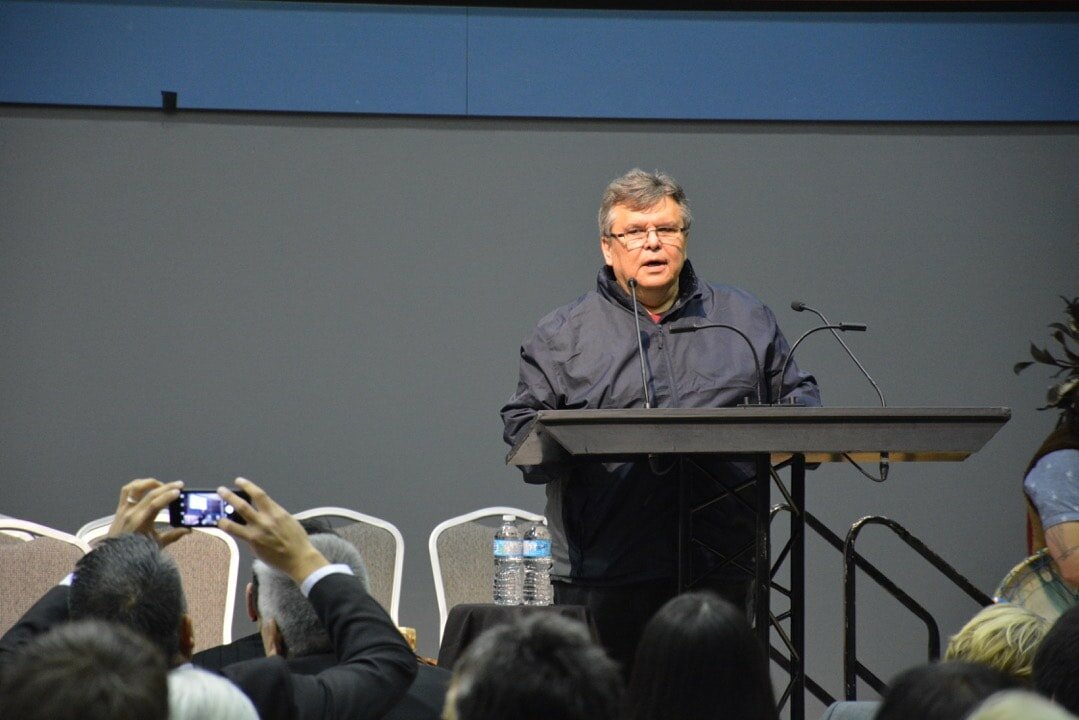

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip worries the new committee gives the perception that proper consultation with First Nations has happened when it hasn’t.

Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs Grand Chief Stewart Phillip isn’t worried about the newly formed Indigenous Monitoring and Advisory Committee for the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project, but he is concerned about its optics.

“I am concerned that companies could use the committee to say that consultation with First Nations has taken place,” Phillip tells me.

The committee, which launched last week, comprises 13 First Nations members from more than 100 First Nations and Metis communities, as well as federal representatives. Committee staff will work with federal regulators on environmental and safety monitoring issues and ensure Indigenous interests are protected as the pipeline passes through First Nations and Metis lands from Alberta to B.C.

Phillip has been an ardent vocal critic of the pipeline project, even participating in protests about it.

Proponents say that establishing an Indigenous oversight committee is prudent because, if the fight to stop the pipeline fails, construction could proceed without someone protecting the very interests being fought for to begin with. Opponents, however, say that, while the committee seems insignificant in the face of widespread protest over the pipeline proposal, it gives the perception that consultation with First Nations is taking place when it isn’t.

How the committee came to be

Cheam First Nation Chief Ernie Crey was at the National Energy Board hearing into the expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline, in Burnaby, last year. Cheam representatives made a submission to the hearing, and something triggered his instincts, which were honed from more than 50 years advocating for Indigenous issues.

The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion was approved by the federal Liberals last November. The plan will see 890,000 barrels of oil a day flow through Kinder Morgan’s 1,150-kilometre pipeline from Alberta to B.C., then to tankers on the West Coast, effectively tripling the existing pipeline’s capacity. Work on a Burnaby pipeline facility starts in August and more construction is set to take place in December.

Crey had a hunch — just a hunch, he says — that the National Energy Board would recommend approval of the expansion, and he was at a loss as to where First Nations along the pipeline route would be afterwards. “Everyone was preparing for a fight to the end with this, but no one was preparing for if that fight was lost,” Crey says. “I asked myself, ‘Where do First Nations want to be: on the outside of work sites looking in with no role to play and unable to represent our interests, or inside them working with regulators?’”

In the ensuing months, Crey networked with other First Nations along the pipeline route to ponder where they wanted to be positioned if it were to be built. At one of those meetings, he listened to University of Southern California professor Najmedin Meshkati talk about the importance of the independent safety oversight committee connected to the nuclear power facility at Diablo Canyon, California.

“First Nations in Canada operate in a different constitutional and legal environment than in the U.S.,” Crey says. “There’s a duty to consult in Canada, and I thought that an Indigenous oversight committee might be one vehicle where that could be accomplished.”

In June 2016, Crey and Lower Nicola First Nation Chief Aaron Sam joined 46 other First Nations and penned a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and former B.C. Premier Christy Clark. The letter outlined what the chiefs said was inadequate consultation over the pipeline and the need for an Indigenous oversight committee. They received a favourable reply shortly thereafter. The federal Liberals approved the pipeline expansion in November. A statement from Natural Resources Canada noted that “Establishing the IAMC was a key element in the Government’s decision to approve the project.”

Ottawa is underwriting the committee’s operation with more than $64.7 million over five years to contract engineers, biologists, hydrologists and wildlife specialists. The group will make recommendations to federal regulators such as the NEB, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Transport Canada, and ensure

First Nations interests are protected to the highest standard as the pipeline passes through First Nations and Metis territories. The committee will get to work right away as construction begins on the pipeline facility in Burnaby in mid-August. More construction is slated to start in December.

Crey says establishing the committee shouldn’t be viewed as acquiescing to government or companies. If anything, the bigger fight is maintaining the integrity of Indigenous interests during construction. “No, we’re not throwing in the towel. We’re in the ring fighting to protect our interests, and if anything, that means taking on a lot of responsibility to do it,” he says.

The committee may have been Crey’s idea, but the mandate to establish it came as a result of consultations over six months with First Nations and Metis communities along the pipeline route, he says.

The committee includes tribes that don’t support the pipeline expansion. The Tsleilwaututh First Nation is a member of the committee and has publicly opposed the project since the start. Tsleilwaututh officials didn’t return repeated calls to clarify their involvement with the committee. Councillor Charlene Aleck reported on the tribe’s Sacred Trust blog that the project may have some federal permits in place, “But it certainly does not have the consent of local First Nations or the permission of the people of BC who just voted overwhelmingly for parties who opposed the project.”

Crey wouldn’t speak for the Tsleilwaututh. But he pointed to a without-prejudice clause in the committee’s terms of reference that accommodates membership for First Nations who oppose the project so they could still have a voice.

Natural Resources Canada officials noted in a statement that some Indigenous communities support the pipeline expansion and some oppose it. Participating on the committee doesn’t mean that a community supports or does not oppose the project, the release reported.

B.C.’s now-governing provincial NDP is also against the project. Premier John Horgan said before the election that consultations with First Nations were among the tools he would employ to stop the pipeline. Committee officials copied the letter to Prime Minister outlining the oversight body to then B.C. premier Christy Clark last June. Horgan’s office didn’t respond to requests for an interview but said he would have more to say about the committee in the coming weeks.

Issues with the optics

The Indigenous oversight committee doesn’t come as a surprise to Phillip. Committee officials corresponded with the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs leading up to the launch, even asking them to join — they didn’t.

“We have every intention of following our mandate to carry on our active opposition to the pipeline expansion proposal,” Phillip says. “The creation of this so-called committee isn’t going to have any impact on that.”

Phillip takes issue with the optics of the committee. Governments and industry, he says, are notorious for creating such bodies that give the appearance of First Nations support for the pipeline when that’s not the case. Indeed, Kinder Morgan is facing multiple lawsuits over the pipeline, First Nations suits among them, and this dispels any notion of universal cooperation. “We wouldn’t be in court. We wouldn’t be supporting political campaigns if that were the case,” Phillip says.

"We’re starting now at the ground floor where we will have the most influence." The committee is a small development set against a larger backdrop of opposition to the pipeline expansion. Phillip says that a majority or British Columbians oppose the plan, although a Mustel poll reports 44 per cent of more than 500 people polled oppose the pipeline expansion. As well, the outcome of recent provincial election, which saw the BC Liberals lose power after 16 years, is a consequence, particularly in the Lower Mainland, and rebukes the pipeline plan, Philip added.

“I’m not the least bit concerned about the existence of this committee in terms of it turning the tide in the face of these broader issues,” he says.

The plan has incurred backlash from First Nations, environmental groups and from the now-governing BC NDP. As recently as June, UBCIC participated in a campaign that saw 20 Indigenous and environmental organizations call for 28 major banks not to underwrite the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. “Mark my words, Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project will never see the light of day,” Phillip noted in the letter to the banks.

Consultation or confusion

The committee adds another element to the mix of consultations with First Nations over resource development projects, which Canada’s legal and constitutional framework requires.

The federal Liberals promised reforms to the NEB after being elected, particularly the project approval process. An independent review panel recommended, for instance, that consultations with First Nations over pipeline projects be extended beyond the current 15 months.

But two recent Canadian supreme court judgements have also affected consultation with First Nations. In the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation v. Enbridge Pipelines Inc., the court ruled that the NEB adequately consulted with potentially impacted First Nations groups about Enbridge’s plan to reverse the flow of crude oil on its Line 9 Pipeline, which flows through Chippewa territory. The court further ruled that consultations with First Nations aren’t a veto over final crown decisions.

Conversely, the supreme court ruled that the NEB didn’t adequately consult with the Inuit in Clyde River about seismic testing. It didn’t hold oral hearings, didn’t provide the Inuit with intervenor funding and responded to their questions with a 3,900-word online, English document emailed to an area with poor Internet access.

In short, the consultation process is a muddle and along comes an Indigenous monitoring and advisory committee with the Transmountain pipeline expansion project. Does the committee further muddy the consultation waters? No, Crey says.

“We're working with what's in place now knowing that in the not too distant future the regulatory environment is going to change and the committee is there,” Crey says. “We’re starting now at the ground floor where we will have the most influence. We’re not waiting until later after it’s built.”