One northern Canadian town's four-decade battle to ditch diesel

With five metres of rainfall each year, the First Nations village of Hartley Bay in northern British Columbia is one of the wettest places in Canada. So why is it so hard to turn their most plentiful resource into electricity?

Part 1

CANADA

- Population: 35.16 million people

- Electrification rate: 100%

- Renewable energy consumption: 20.60%

- Access to non-solid fuel: 100.00%

Source: World Bank

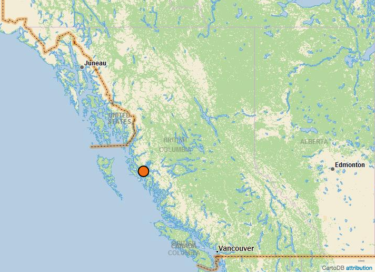

HARTLEY BAY, CANADA — Cameron Hill will never forget the cold October night in 1975 when a diesel generating plant breakdown cut all power to Hartley Bay’s homes and water treatment system. Completely isolated 140 kilometres south of Prince Rupert on British Columbia’s north coast, the village and home community of the Gitga'at First Nation [pronounced “Git-Gat”] was completely on its own.

“Six weeks later the power was still out,” says Hill, 47, now the school principal and a 20-year Gitga'at band councillor. More than anything else, he remembers watching his family’s winter supply of salmon, halibut, moose and berries defrost and spoil in their multiple freezers.

The great blackout was a defining moment for Hartley Bay. Within three years, a plan emerged to build a small hydro project to replace their unreliable, dirty and expensive diesel, which, like everything else they cannot source themselves, must be shipped four hours from Prince Rupert.

So it’s amazing, nearly four decades on, that the community vision for clean energy remains in limbo. It certainly hasn’t been for lack of effort: the Gitga'at have successfully navigated the complexities of multiple government bureaucracies, lined up millions in loans and grants, and were even awarded an energy purchase agreement in 2014. But it has not been enough. The hydro project is stalled, forcing Gitga'at leaders like Hill to face another generation burning the same dirty fuel.

“My mom and dad fought to have hydro,” says Hill, who remains one of the community’s biggest hydro champions. “Now my generation is fighting for it too.”

Stuck on dirty diesel

Hartley Bay is just one of an estimated 175 remote communities across Canada that must burn diesel fuel to generate electricity. Most are aboriginal hamlets where energy poverty is deeply intertwined with access to clean water, food security, and limited economic opportunity. Diesel is dirty, toxic, its price volatile, and many First Nations must bring it in by expensive and often seasonal truck, ocean-going ship, rail, or even by air. Spills are commonplace across the north.

But despite available technology and much talk about ramping up clean energy to avoid catastrophic climate change, aboriginal communities still face enormous barriers in escaping their energy dependence on fossil fuels.

Hartley Bay was one of the first remote BC coastal communities to get “electrified” by diesel in 1928, a project funded by the Gitga'at themselves. On a Tyee visit to the community in January 2016, elder and Hereditary Chief Ernie Hill Jr. (Cameron’s dad) recounted his mother’s experience at a 1928 feast to celebrate the first electric light. It was otherworldly technology to most, he said. Some marvelled at how oil could be fed through transmission wires that were so thin and one visitor to the community cut a light bulb from a wire, in hopes of taking the light home.

That was then. For the 180 Gitga'at who live in Hartley Bay today, life on diesel has become untenable: the cost of generation is on the rise, brownouts and power surges are common. Christmas day of 2012 saw most of the village men huddled around the generator — they were trying to fix the cooling system in time to get their turkeys in the oven.

Bills from BC Hydro, which operates and maintains the diesel plant and charges the locals for usage, remain a bone of contention. Despite the installation of smart meters in 2013, inexplicable discrepancies exist in power bills, neighbours complain. Meanwhile, over 500,000 litres of diesel must be shipped in by barge each year, putting local waters at risk. In 2008, a faulty gauge on a storage tank caused 10,000 litres to spill into the ocean.

While the imperative to get off diesel has been mostly economic over the years, awareness of the the greenhouse emissions their power plant pumps out — at least 2,000 tonnes a year — strikes close to home.

“Hydro makes business and environmental sense,” says Cameron Hill. “Especially coming from a people who still live off the land and don’t want to contribute to climate change.”

The hydro vision

Hydro also makes a lot of sense in a place where almost five metres of rain falls each year.

Hartley Bay is so wet that buildings must be constructed on wooden stilts driven deep into the swampy edges of the sea. To get anywhere in the village, you must navigate a system of wooden boardwalks built above the spongy muskeg. “Our Elders have said, ‘We must take advantage of what God gave us,’” recounted Cameron Hill. “And that's water.”

“Our Elders have said, ‘We must take advantage of what God gave us.' And that's water.”

Ernie Hill recalls that the federal Department of Indian Affairs briefly viewed getting Hartley Bay off diesel as a priority (this was during the oil “price shocks” of the early 1970s that saw price spikes and shortages). But after a pre-feasibility plan in 1978, the federal government ultimately balked at the CAD$1-million price tag as oil prices settled back down.

Successive chiefs and councils, however, never lost interest. The “run-of-lake” design currently envisioned would see a small dam built on a lake above the village to ensure there's always enough water to make power. A pipe would channel the water down to a powerhouse where it will turn generators before being released back into the Gabion river, which bisects the village and flows out to sea.

The vision guarantees energy security for the community: the diesel plant will be maintained and at the ready, but only as a back-up if the hydro plant goes down.

A health issue, too

Among the first things I noticed about the Cameron Hills’ spacious bungalow — other than lots of guns and a pirate flag flying out front — was that the wood stove is always on.

BC Hydro’s mantra of putting on a sweater and turning down the heat is not an option here: without steady heat, mould would devour the houses of Hartley Bay, and worse. The local clinic has historically reported high incidences of bronchial, nose, throat and ear problems such as Otitis media in children, that are thought to be linked to exposure to mould.

The Hills buy wood pellets, made from pine trees killed by the mountain pine beetle, by the tonne from a company in Prince Rupert. Others rely on heaters that burn diesel and heating oil, as expensive and prone to spill as the stuff used at the power plant. But keeping the mould away has its own dangers. Days before I arrived, a house in the village burned to the ground when a damaged plug-in space heater was left unattended.

And therein lies one barrier to getting Hartley Bay its hydro. Fixing and replacing housing on the reserve has to take priority over the new power plant, and there are only so many financial and human resources to handle so many projects. (At least 10 new houses are being built on the reserve this year alone, costing millions.)

And like many other First Nations, successive Gitga'at band councils have found themselves in perennial crisis management mode, dealing with capital demands as they come up. A Hepatitis A outbreak in Hartley Bay in 1997 necessitated a costly revamp of the community’s water treatment plant. A new sewage treatment plant looms on the horizon — another $1 million.

An unequal contest

With fewer than 200 people (another 450 Gitga'at live off-reserve), the community has also been forced to navigate a maze of government jurisdictions and funding bodies in pursuit of its clean energy vision.

That experience is widely shared in off-grid Canadian reserve hamlets, says Liane Inglis, who wrote her 2012 Simon Fraser University thesis on the barriers to clean energy development in remote BC communities.

First Nations like Hartley Bay must not only work within their own complex governments (including the often grey jurisdictional zone between elected band councils and hereditary chiefs), but are forced simultaneously to interact with the federal Aboriginal Affairs department, provincial ministries and BC Hydro. The effort can easily overwhelm capacity, she concluded.

WHY DO YOU CARE ABOUT ENERGY SOLUTIONS?

Tell us about the solutions you see. Be in touch

Hartley Bay moved forward where it could. Beginning in 2010, it participated in BC Hydro's Remote Community Electrification Program (the program was suspended in early 2015). That led to an agreement by which the Crown utility would buy all the hydro the project generates — and then sell it back to the reserve residents who consume it. Once the project’s debt is paid off, the revenues will flow to the First Nation.

For the hydro project to move forward, the Gitga'at needed a buyer for their energy, and through their EPA agreement, BC Hydro became that buyer. Before that could happen, however, the village’s aging transmission infrastructure needed a costly and time-intensive upgrade to meet BC Hydro standards.

Some might say that getting this far is an achievement in itself for Hartley Bay. The progress has a lot to do with an unlikely combination of events from outside the tight-knit community: the arrivals of a clean energy champion — and an agent from a pipeline company.

Part 2

Stuck On Diesel: The Lure and Challenge of Clean Power for Remote First Nations

By the time the Great Recession of 2008 hit, Hartley Bay’s decades-long struggle to shed its reliance on diesel was in a precarious place. The complexity of navigating multiple funders and governments with limited funds and human resources was becoming overwhelming.

Then Enbridge, operator of the world's longest crude oil and liquids transportation system, came to town.

Roger Harris, a former BC provincial politican and Enbridge’s point man for aboriginal relations, visited the isolated reserve, 140 kilometres south of Prince Rupert on British Columbia’s north coast, in February, 2009. He arrived knowing the community of fishermen, dependent on salmon and eco-tourism, was vehemently opposed to his company’s plan to build a pipeline from the Alberta oilsands to the north BC coast, turning the Gitga'at's stretch of pristine coastline into a high-traffic oil tanker route.

At a private meeting between Enbridge and Gitga'at leaders in February 2009, according to several band members, Harris argued that the Gitga'at rely on diesel for electricity, so why shouldn't people in foreign countries who need fuel for electricity be able to have that as well?

The Giga'at leadership was incensed. They had struggled for decades to build a clean hydro plant and transition off diesel. Harris’s words now fuelled their resolve.

A project champion emerges

As it happened, Hartley Bay’s energy file was by then in fresh hands. David Benton, a Vancouver lawyer and business school grad, arrived serendipitously, accompanying his partner at the time, who is Gitga'at, on a visit to their home. Smart, articulate and intense, Benton soon found his skills in demand, first as health manager, then as band manager, and eventually as the hydro project manager.

In 2012, the Gitga'at signed an energy purchase agreement in which BC Hydro guaranteed that it would buy the power the village generates. Benton and the band negotiated $10 million in grants (US$7.6 million) and an additional $12 million (US$9.1 million) in financing. It would take 25 years to pay off, but after that the project promised to generate net revenue for the Gitga'at nation.

The project’s design evolved as funding doors opened, but costs were escalating. Many stemmed from the Gitga'at’s insistence on self-reliance. A two-way fish ladder to protect local stocks and other mitigation measures would cost $1.5 million (US$1.1 million). A six km road and buried transmission lines would consume another $6 million (US$4.6 million). But memories of the great blackout of 1975 linger. If the plant ever went down for any reason, the community refused to be dependent on the outside world to get it fixed. But self reliance comes at a price: all in, the project cost today is estimated at $25 million (about US$19 million).

As of March 2015, Hartley Bay’s hydro plant remains in limbo, with no clear path forward.

Paying now or paying later

“It’s an expensive project,” says Christopher Henderson, the author of Aboriginal Power: Clean Energy & the Future of Canada’s First Peoples, of Hartley Bay’s dream.

Perhaps no one in Canada knows more about what it takes for remote First Nations to get off diesel. Henderson has consulted for Aboriginal Affairs and today advises or represents numerous First Nations trying to develop clean energy. But despite available technology and strong interest, he says, many barriers remain.

As he explains it, the different cost curves of diesel and clean energy stack the cards against change for many small and cash-strapped communities, even if it could mean long-run savings. Diesel generation requires only a modest up-front outlay of capital; 85 per cent of the cost is in ongoing fuel purchases. Clean energy projects like small hydro, by contrast, require big capital expenditures upfront. Positive economic returns over the longer term, such as net revenue for decades ahead, often do not influence the short-term decision.

“We have a say in how we want our future to look, so why wouldn’t we be green? Being green just fits who First Nations people are.”

“This is not a technology issue,” says Henderson of the barriers to clean energy in remote places. “It’s a combination of community capacity and leadership, coupled with the right fiscal environments to recognize the true costs of diesel power.”

Henderson is trying to tackle the second problem by launching what he calls the 20-20 Catalysts program, which pairs Canadian First Nation communities seeking to get off diesel with mentors. He hopes it will create and nurture ‘project champions’ with the skills to push projects into being. (On the day I talked to Henderson, he was talking with David Benton about Hartley Bay.)

‘We’ve done it and we know how’

His highest profile mentor is probably Peter Kirby, an energy pioneer and citizen of Atlin BC’s Taku River Tlingit First Nation. He spent a decade navigating funding and bureaucracy on the way to completing a 2.1 MW hydro project for the community in 2009. Now he’s taken on the mentor’s role because, he says, “We’ve done it, and we know how to do it."

From the beginning, Kirby and other project leaders consulted their neighbours, a vast majority of whom supported the plan. They lined up an investor on very good terms (insurance company Canada Life), tapped money from EcoTrust’s First Nations Regeneration Fund and later enlisted help from the First Nations Finance Authority. They hired an innovative contractor who shaved hundreds of thousands from construction costs. And when it came to designing a corporate structure to develop the project, they created a limited liability company that operates at arm’s length from the local politics of the community.

Then there was the all-important confidence factor: “When we said something was going to happen, people [outside the community] knew it was going to happen,” Kirby says. “I can’t emphasize the importance of that enough.”

Today, Atlin’s diesel generators are maintained and ready, but usually silent. A plan is afoot to expand their hydro project to 5 MW (pending community approval) and sell the excess power for profit to the Yukon electrical grid, with the profits flowing back to the First Nation.

Wind, solar and geothermal too

While the Gitga'at have nearly five metres of annual rainfall, a site on the edge of Kluane Lake in the Yukon has an average wind speed of six metres per second, which is ideal for the three 95-kilowatt turbines that should stand on this site before the end of the year.

With advice from Kirby and the leadership of two-term chief Math'ieya Alatini, the Kluane First Nation of Burwash Landing, YT, is developing the project to minimize its diesel consumption. It’s also pursuing solar, geothermal and biomass energy sources.

The wind project will reduce the need for diesel generation by a third. Their oil consumption is already down because the community burns 100 cords of pine-beetle-salvage wood ‘biomass’ annually (it’s fed into a chipper and wood-fired boiler that currently heats over 12,000 square feet of indoor space in the community). Alatini says there’s enough beetle wood to keep the community warm for the next 20 winters.

Solar panels provide electricity to a municipal building, and plans are afoot to source geothermal energy from a faultline that underlies Kluane land. (Predesign work should be done this year to pipe warm water up from the earth to heat a greenhouse.) Alatini’s dream is to establish a closed-loop greenhouse food system that will grow tilapia and fertilize vegetables with the fish waste.

“We have a say in how we want our future to look, so why wouldn’t we be green?” she asks. “Being green just fits who First Nations people are.”

Hartley Bay: still in limbo

On March 4, BC Hydro started accepting applications for its latest “standing offer” program to help First Nations and other small, off-grid communities develop very small-scale (between 100-kilowatt and 1-megawatt) clean energy projects. The program is designed to streamline the complexity of the process. But it comes too late for Hartley Bay, which has already negotiated many of the hurdles it’s meant to sweep away.

At around the same time, Hartley Bay’s own leadership dealt David Benton some disheartening news. After nearly eight years of pushing hard for a hydro project close to the village, he learned that the community’s leaders are considering an alternative: a cheaper project that would involve running an undersea cable from the community to a nearby island.

The new plan would trigger a new federal environmental assessment screening, and extend years of red tape.

Benton was asked if he was still willing to be involved, a question that forced him to think long and hard.

“First and foremost, my relatives live here,” said Benton, whose recent adoption into the Gitga'at Raven Clan marks his acceptance as a member of the community. “I have experienced what no electricity is like here, so I said yes.”