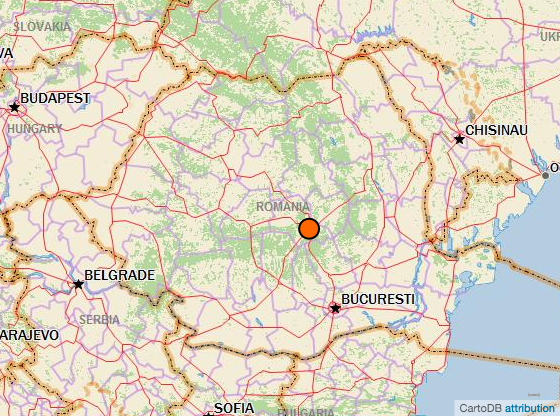

In Transylvania, energy poverty persists in the developed world

Romania has been a European Union member state since 2007, yet today 100,000 households continue to languish in the dark. A group of Romanian volunteers is fighting to change this.

Search all Discourse content.

Close

Follow our reporting and get involved. Sign up for our newsletter.

Close

Romania has been a European Union member state since 2007, yet today 100,000 households continue to languish in the dark. A group of Romanian volunteers is fighting to change this.

Power StruggleFelix Gaedtke | April 19, 2016

Romania has been a European Union member state since 2007, yet today 100,000 households continue to languish in the dark. A group of Romanian volunteers is fighting to change this.

Source: World Bank

HOLBAV, ROMANIA — “It sucks,” said 12-year-old Boboc Codrut Sergiu about his life on the outskirts of Holbav, a hilly village in Transylvania, central Romania. “There’s no electricity. It really sucks,” he repeated, sitting in the near darkness of his living room. The only ray of light came from a couple of battery-powered LED bulbs hung from a bunch of wires on the ceiling.

Under these dim lights, Sergiu and his six-year-old sibling Boboc Serafino Oliver played with a couple of red balloons that evening. They threw the balloons at each other, played catch with them and eventually got into a friendly fight, which ended with Oliver bursting one of the balloons.

“Sometimes when it’s really dark, when there’s no moon, we are afraid to step out. If we had electricity, we could turn on the light outside in the courtyard. But we got used to playing in the dark at home. We play hide and seek often. We hide in the sleeping room,” Sergiu said, pointing towards the adjacent room, which was pitch dark.

Sergiu and Oliver are two of thousands of Romanian children growing up in darkness. These houses, often located in remote mountain regions, lack connection to the existing national electricity grid. Most are located in poor communities.

The Bobocs are among the energy poor citizens of Romania. “I am in a rush to finish homework on most days,” Sergiu said with a sigh of resignation. “After I return from school, I change my clothes, I eat and it’s already late. If we had electricity, I wouldn’t be in a hurry when I write, so I wouldn’t write so ugly anymore. I would write slowly and much prettier.”

NowHere Media

In the evening Sergiu and Oliver’s father, Boboc Sorin, fed the stove with wood to keep warm. Sorin is a construction site worker, who was born and raised in that very house.

On their living room wall hung a framed painting of Jesus Christ and nearby was a kitsch poster with two brown horses galloping on lush green fields. The room had one window with a view down the valley. The house was crammed with furniture — a table, closet, bed, a couple of sitting stools and a wood stove for heating and cooking.

“I never had electricity in my life here,” he said earlier in the day. “When I was a child, it was the same, I was doing homework by an oil lamp. We would still find gas in those days, now you can’t find gas anymore. That’s the problem. Now I can’t buy gas anywhere.”

When he got married, Sorin moved to live with his wife in the village, which is connected to the electricity grid. He returned to the hills about three kilometres outside of Holbav some years later after they got divorced. Today, Sorin takes care of their children by himself.

“I had this battery from a scooter that stopped working. So I connected this small bulb to the battery. I am happy now I have light in the house. Once a week I go down to the village to my brother-in-law’s house to charge the battery. It charges in about three hours,” he said.

Sorin also owns a mobile phone and gets it charged at his brother-in-law’s house in the village, which is connected to the grid. His boys drop the phone at his brother-in-law’s home on their way to school every day and pick it up on their way back once it’s fully charged.

There are nearly 400 people in Holbav, a village in Brasov County, central Romania who don’t have access to electricity. A few of them have been provided with solar panels by a non-profit called Free Miorita.

Twelve-year-old Boboc Codrut Sergiu and his six-year-old brother Boboc Serafino Oliver play with balloons in the dark after sunset. “We are scared to step out of the house in the dark,” Sergiu says.

Some houses in Holbav are connected to the electricity grid. The electricity market in Romania is split between public and private players, with Electrica, the state owned company, being the largest provider.

Boboc Sorin’s sons Sergiu and Oliver drop his mobile phone at his brother-in-law’s home to have it charged on their way to school. On their way back, they pick up the fully charged phone.

Boboc Sorin was born and raised in Holbav. He says he has never had electricity in his home.

Boboc Sorin, a shepherd, partially solved the problem with the lack of light at his home with an innovative approach. “I had this battery from a scooter that stopped working. So I connected this small bulb to the battery. I am happy now I have light in the house. Once a week I go down to the village to my brother-in-law’s house to charge the battery. It charges in about three hours,” he said.

Sorin joked and smiled frequently. With every smile, his decayed front teeth showed. He kept a stubble, his hands were dry and overworked. His clothes — a hat, thick woollen jacket, pants and gumboots — were dusty from working on the farm.

“Nobody ever told us that they would bring electricity here. The mayor told my brother that it’s too expensive to bring electricity up to the houses on the hills,” he said, before stepping out to feed his cattle that day.

The electricity market in Romania is split between public and private players, with Electrica, the state-owned company, being the largest provider. Currently, electricity in Romania is harnessed from hydro, thermal, nuclear, wind, solar and biomass sources.

The mayor’s office in Holbav is a grey house with glass doors in the village centre. On the day we visited him, Oprea Lucian Vasile — a chubby man with a double chin and green eyes — sat on his leather chair behind a desk. He accidentally knocked the European Flag off his desk as he walked over to greet us. On the peach-coloured wall behind him hung a painting of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. On the opposite wall was a map of Romania.

“There are 1,305 people in the village and about 380 don’t have light here. About 70 per cent of the people who don’t have electricity live on one side of the hill and 30 per cent on the other side. We are currently running a program to electrify homes on the hill where the majority of homes are,” Vasile said, clicking his pen.

“The houses on the hills are far apart from each other,” he said, as he drew up a map of the homes on the hills on a sheet of paper. “The law requires us to do a viability test [to check return on investment] before we lay electricity cables up on the hills. If we do that test, I am sure it will fail.” The viability test is meant to ensure that an electricity provider finds it profitable to invest in installing transformers in sparsely populated regions.

“The last electrification project for 30 houses cost 150,000 euros (US$170,000), i.e. 5,000 euros (US$5,600) for one house,” Vasile said, as he frantically keyed in numbers on his calculator. The project was partly paid by Electrica, the state-owned electricity provider, and partly by the local village administration. This project took off before the law requiring mandatory viability testing. However, now with the new law in place, Vasile believes no company will want to expand the grid, given the very low return on investment. “And I do not believe that, with the money and budget we have at the local level, we can do that either,” he said, shrugging his shoulders.

According to the National Electrification Plan 2012-2015, the Romanian government was expected to invest 230,000 euros (US$260,000) in electrifying the 100,000 homes without power. That’s a mere 2.30 euros ($2.60) for every unelectrified household. Moreover, the mayor says he has yet to see any of that money allocated to his village.

Last year, a fire at a Bucharest nightclub killed 32 people and led to anti-corruption protests against the government. The events resulted in the resignation of former Prime Minister Victor Ponta and his government. Currently, Romania has a transitional government led by Prime Minister Dacian Ciolos.

The energy sector in Romania, like many others, is riddled with allegations of corruption. Daniel Befu, an investigative journalist, has been researching the subject for several years now. Over a Skype call from Timisoara county in northwest Romania, Befu said, “If we talk about general contracts in Romania, the bribe is between five and 25 per cent. In some industries, the bribe is even as high as 40 per cent. Money is taken at all levels. Usually whoever generates the project takes most of the money.”

Befu added that there are often close links between companies involved in the energy sector and politicians in power. “I can give you an example of the father-in-law of the former Prime Minister. He was very subtle and made a lot of efforts to make his businesses look clean.”

Befu was referring to the case of a micro hydro electric plant company called Elcata MHC SRL, which triggered an EU criminal probe (which is ongoing) into Romania’s potential breach of EU environmental regulations. The allegations included Romania allowing Elcata to set up hydro power plants in the Fagaras mountain range, which has been declared a protected area. One of the associates of the company is Ilie Sarbu, the father-in-law of former Prime Minister Victor Ponta and a former Vice President of the Senate.

“I can give you many such examples,” he said. “Three former Prime Ministers, Mihai Razvan Ungureanu, Victor Ponta and Nicolae Vacaroiu, have directly or indirectly had contracts with the biggest energy company in Romania, Petrom, an oil producer. So energy is a place where politicians traditionally like to delve in.”

Despite several requests, the Energy Ministry of Romania declined an interview.

Palace of the Parliament in Bucharest, Romania. According to government reports, nearly 100,000 households in Romania lack electricity.

While the capital city of Bucharest has enough electricity, remote communities living in the countryside are not connected to the national electricity grid.

Iulian Angheluta, founder of Free Miorita, at a cycling rally in Bucharest. Iulian’s non-profit organisation has provided solar panels to 35 homes and four schools.

Currently electricity in Romania is harnessed from hydro, thermal, nuclear, wind, solar and biomass sources.

Some houses in Holbav are connected to the electricity grid. The electricity market in Romania is split between public and private players, with Electrica, the state owned company, being the largest provider.

Back in Holbav, a black dog chained to a post barked ferociously at the door of Eugenia Fota’s house. A few chickens walked around the sunny courtyard bobbing their heads. Inside the house, the living room was cluttered by a dozen buckets on a shabby rug. Fota, with five children of her own, and her sister with four children, shared the small, two-room house.

“I left my husband’s house because he used to beat the kids. He was violent, very, very violent. And that’s why I came back here, where my parents used to live. Now I take care of the children all by myself,” Fota said. The barking dog outside had calmed down.

Fota sat next to the only table in the room. A couple of battery-powered flashlights stood on it. “We never had electricity in the house here. When they put electricity on the other side of the hill, they told us they would do the same for everybody on the hill, but it didn’t happen,” said Fota as a black cat with white patches crawled into the room and squeezed itself under the bed.

“It is very bad… we can’t have a radio, we can’t have a washing machine. Let alone fridge or anything else.”

We’d love to hear your story. How are you impacted by the issues we’re reporting on? What solutions do you see? Who is inspiring you? Get in touch.

Despite these problems, Fota said there was one big change to her life last year. “There were two boys who came one day and said they wanted to help us. The next day six boys came and installed the solar panel.” On a sunny day, the solar panel on her roof produces enough power to charge a couple of mobile phones and run some energy-saving bulbs. “Since then, there is a bulb that we can turn on. At least you can see a bit, not like with the lantern,” she said, pointing toward a strip of LED lights taped to the ceiling.

Four children, curious but shy, queued up next to the door and peeked into the living room as their mother spoke to us. “When we didn’t have the lights, we had to buy lanterns nearly every week because we have very small children and they go out and break it sometimes. The kids had to take turns to do their homework next to an oil lamp, especially in winter or if they came back from school late,” she said. “Now with the LED light, they can do their homework all at the same time. And I don’t have to walk around with the oil lamp inside the house after it’s dark.”

The men who came to install the solar panels on Fota’s roof were volunteers from the NGO Free Miorita, which has been running a program called Light for Romania since 2011 to provide solar panels to those without electricity in Romania.

On a Saturday morning, Free Miorita founder Iulian Angheluta and his colleague Ionut Vlad met us at a garage in a residential quarter of Bucharest. “This is my personal garage, but I also store the solar panels and batteries for the Light For Romania project,” Angheluta said.

Despite its being a cold day, Angheluta wore shorts and hiking boots. He pulled out a camping table, a few camping chairs from the garage and folded them out to make room for sitting.

Angheluta recalled the time when the seed for the Light For Romania project was sowed. Back in 2008, during Christmas holidays, he went on a cycling trip with some friends to Hunedoara county in northwest Romania. “We went there to hand out some Christmas gifts, clothes, food etc. It was winter and I discovered that people in this village don’t have electricity,” he said, brushing back his lank hair.

It was a coincidence that Angheluta discovered a lack of electricity in rural Romania, but he soon resolved to do something about it. The following year, he returned to learn more about the village, which is called Ursici. “I found out that the authorities had put out a plan to extend the grid. And year after year, they did nothing. So the plan remained just on paper. In 2013, I then set up a campaign to light up that village. We raised the money and installed panels the same year,” he said.

Angheluta and his team soon realized that there were many villages like Ursici in Romania. Three years after the project’s inception, they have raised 50,000 euros (US$56,000) in donations from corporate and individual contributors. With the money, they have provided solar panels to 35 homes and four schools in rural Romania.

“There are still families that don’t have enough food or water or health care. There are many pieces missing in this picture,” Angheluta said. “So we are aware that by giving them light, we are just going one step ahead.”

Angheluta’s team of volunteers faces many hurdles on a practical level. Vlad, who implements the project on the village level, jumped into the conversation. “It is hardest to gather information about how many homes lack electricity — how many people live in them, how many of them have children etc. The authorities are not so responsive to our questions. For example, it took us about three months to get a list of all households in Holbav — the village you visited,” he said. (To date, the group has installed seven solar panels in Holbav.)

Currently the law in Romania doesn’t allow the use of public money on private properties. That means projects that involve setting up distributed or decentralized energy systems like solar panels on individual homes cannot be paid for by government funding. “The only way for the government to provide electricity is through the grid, even when it’s much more expensive,” Vlad pointed out.

The reality that the Romanian government cannot and is not taking any initiatives to promote distributed energy systems upsets Angheluta. “There’s no law or framework that encourages the government to think locally, like putting up solar panels or other renewable sources, instead of setting up a grid that is powered by a nuclear power plant or thermal energy,” he said. “They aren’t thinking ecologically or socially. They are only thinking from a business perspective.”

Even though solar panels have their limitations with providing power — especially during winter when it doesn’t get very sunny — Angheluta believes this is the way forward.

“The ideal scenario would be for the government to be involved with us. Even to light up 1,000 homes will take us years. And there are 100,000 homes in Romania without electricity.”

Discourse Media is an independent journalism company dedicated to in-depth reporting on complex issues. We are building a home for new approaches to storytelling that look beyond conflict-driven daily news cycles.

GET INVOLVED

We’d love to hear your stories. How are you impacted by the issues we’re reporting on? What solutions do you see? Who is inspiring you? Get in touch.

WORK WITH US

Learn about our products and services.

© 2016 Discourse Media Inc. Privacy Policy Terms of Use