A solar revolution is bringing light and opportunity to the Bangladeshi countryside

Solar power micro-grids are reaching isolated corners of Bangladesh. But will it be enough to offset a future of dependence on dirty coal-fired electricity?

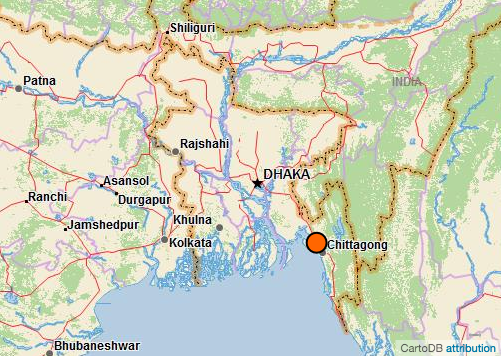

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

- Population: 156.6 million people

- Electrification rate: 59.00%

- Renewable energy consumption: 38.30%

- Access to non-solid fuel: 10.91%

Source: World Bank

KUMIRA GHAT, BANGLADESH — The channel that separates Guptachara Ghat of Sandwip, a small island in the Bay of Bengal, with Kumira Ghat of Chittagong on the mainland is 18 kilometres wide and swept by tidal currents. For some 350,000 island dwellers, the only way of getting in and out is by speed boat or trawler.

Speedboats cost US$3.83 per ride and take about 25 minutes, while trawlers are just one-third of the cost but take almost an hour and a half. On an overcast February morning, nearly two-thirds of the 300-plus people gathered at Kumira Ghat en route to Sandwip purchased tickets for speedboats.

Mahbubur Rahman, an assistant teacher at a government primary school in Sandwip was among them. He earns a meagre monthly income of Tk 16,480 (US$210.22), but was among those who preferred speed over saving money.

“Most of Sandwip’s people now prefer that,” Rahman, a man of short stature and betel leaf-torn teeth, told me later as we shared an engine rickshaw to Enam Nahar Market in Muchapur Union [in Sandwip] from Guptachara Ghat.

“Everything is relatively expensive here. We neither grow many crops, nor do we have many industries. Almost all things are needed to be imported from the mainland and the transportation costs raise the prices as a result,” he said, but clarified: “Money is not the big problem here anymore.”

That’s because the islanders have learned to live through trade, making them global fortune seekers. Almost every household has someone living abroad, including Rahman’s, whose sister lives in the United States and sends money regularly.

With this inflow of cash, the demands and aspirations of the people here have increased, said Rahman. Households now wish to upgrade their lifestyles with amenities like television sets and refrigerators. There’s just one problem.

“The national electricity grid has not reached here yet.”

Access to energy is spotty

For Sandwip’s residents, electricity has long been obtained from private diesel generators. If someone buys a 10 kilowatt diesel generator, he/she then supplies electricity to the others through makeshift wires. Such energy is expensive and unreliable; diesel generators can provide electricity for at most six to eight hours a day, and because of makeshift wires and heavy loads (due to demand), these connections were not reliable.

Another way of getting electricity has been through solar home systems (SHS), a success story in the off-the-grid areas of Bangladesh’s countryside. Like other rural parts of the country where the national electricity grid has not yet reached, SHS dominates the power landscape in Sandwip too.

Almost every household in Sandwip has SHS and, based on the availability of sunlight and the size of the batteries, households can access electricity for five to seven hours a day. “But that electricity is enough only for lighting a few bulbs, charging mobile phones and, at most, running a fan,” says Rahman. “As I said, with the inflows of remittances, people now want more.”

Our engine rickshaw stops in front of an unassuming two-storey building in the central part of Enam Nahar Market. Rahman points at the site of the country’s first commercial solar microgrid power plant.

“This has given us the chance to get more."

A Bangladeshi solar ramp up

Today Bangladesh has 3.8 million solar home systems installed — the most for any country on the planet. It’s the result of a ramp-up that started in 2008, when the Bangladesh government moved forward with a plan to promote and prioritize renewable energy sources, particularly solar.

The success of SHS has been a boon to solar microgrid power plants. As of this writing, there are currently seven plants operational in remote areas, with 11 under construction. The goal is to finance 50 such microgrid projects by 2017, with support from the World Bank and at least six other international agencies.

“SHS lightens up people’s households, but for triggering entrepreneurship and lifestyle changes, people need continuous power which SHS can’t provide,” says Asma Haque, chairperson and co-owner of the Purobi Green Energy Limited, which runs the Sandwip solar plant. “Solar minigrid power plants can do that. It can offer significant improvement in socio-economic conditions of the underserved population.”

The stakes for Bangladesh’s solar ramp-up will be high, and not just for Bangladesh. About 13 million rural households still live without access to power here.

If the country cannot significantly boost cleaner alternatives, its future energy path will be to burn up its meagre reserves of natural gas (estimated to run out by around 2030) and after that, to generate electricity using imported high-sulphur coal.

The Bangladesh government has already embarked on mega coal-fired power plants to achieve its ambitious plan of generating 40,000 megawatts of electricity by 2030. As per the plan, half of this electricity will be generated from coal.

But sunlight is plentiful in Bangladesh. Many here believe that instead of pursuing coal-fired power plants, the country should be escalating its use of solar power instead.

Inside a solar microgrid power plant

The resident engineer of the Sandwip plant is a lanky man in his fifties by the name of Mohammad Sakhwat Hossain Khan, who oversees the operation of some 564 solar panels covering about 0.3 acres. Collectively, they have a capacity of 100 kilowatts (the individual panels vary from 200 Watts peak (wp) to 150 wp).“Watts Peak” is the rating given for the total wattage output when the system is operating under perfect conditions. Your system won’t always operate at this level of performance as there are too many environmental variables to take into consideration. However, once in a while you’ll have that perfect day where everything will be calm, quiet and sunny, which will result in your system’s producing this amount of power.

Thanks to the gloomy weather, the amount of sunlight was very low on that day. “But we cannot stop our services because of that, as our consumers subscribe to almost all the 100 KW,” said Khan. “We have battery backup to continue on a day like this.”

WHAT STORIES ARE WE MISSING?

We welcome your ideas. Get in touch.

The microgrid of 100 KW solar photovoltaic (PV) panels is coupled to 80 KW diesel backup generators to continue electricity supply in those seasons when solar irradiation is low and the batteries are low on charge.

“As of now, we have provided a total of 291 electricity connections. Of those connections, 55 are given to households and organizations like schools, mosques and police stations, and the rest to different commercial establishments. We are charging a flat rate of Tk 32 per unit (per kilowatt hour; US 41 cents per unit),” Khan disclosed.

Khan and two of his assistants collect the monthly bills from the consumers. Bill collection is a hassle, as they have to visit every consumer and read the meter themselves. Pre-paid meters could have saved them that headache, but when the plant was established in September 2010, pre-paid meters were expensive and the owners did not find them financially viable for the plant.

HOW THE SOLAR MICROGRID PLANT WORKS

HOW THE SOLAR MICROGRID PLANT WORKS

Unlike SHS, which provides DC (direct current) and works for a fixed number of hours, solar microgrid plants provide AC (alternating current) through a transmission network and provide electricity 24/7.

Some 60 KW of the PV modules are connected to six grid-tied inverters, supplying directly to the 220V microgrid distribution line. The unused portion of the generated power is then stored in the batteries through 12 bi-directional inverters called ‘Sunny Islands,’ distributed in four clusters.

In addition, 40 KW are generated and stored directly in the same battery bank through DC battery chargers. The power plant has a total of 96 batteries in four battery banks which total 12,000 amp/hour at 48V. The battery bank is sufficient to cover the evening load of the market with average insulation.

A three-phase distribution line with a 220V AC bus line is connected to the bi-directional inverter-battery assembly through a multi-cluster interface for the microgrid. From the power station in the central part of Enam Nahar Market, three separate phases extend in different directions, with a balanced load from the consumer’s end. The plant procured its own 5km of distribution lines to supply electricity to the surrounding areas.

Inside a home powered by solar microgrid

Khan took me into a nearby house which subscribed to the connection from the plant. It was a two-storey building, under construction, owned by an expatriate Bangladeshi living in Abu Dhabi. His wife, Alyea Begum, lives there with their children.

Only three years ago, there was just a tin shack on the site, but as her husband started sending money from abroad, she thought of erecting a concrete building. The solar plant aided her in making that decision because it can power a water pump, a television set and a refrigerator in her house. The monthly bill from her house usually stands at around US$28.

Begum is happy with the electricity, but fines for late payment are a sore spot. “They impose fines when I get late in paying the bills. My husband sends money from abroad. It doesn’t always arrive on time.”

Solar grid plant a “life changer”

We also visited Sandwip’s police station in Muchapur Union (one of 16 unions in Sandwip), located next to the plant. The station is one of the biggest consumers of the plant’s electricity with monthly bills hovering around Tk 12,000 to Tk 13,000 (US$153 to $165).

"In my union, people have no such plant. A solar plant like this would have transformed the lives of people there."

Mohammad Abdus Salam, commanding officer of the station, said the electricity in the building previously came from a diesel generator provided by the government. “We don’t use that anymore unless we need back-up. It is costly, unreliable and available only for six hours. The electricity from the plant is available all the time and there are no power cuts. We are very happy with that. Plants like these should be established elsewhere in Sandwip,” he said.

Mohammad Mizanur Rahman, the chairman of Maitbhanga union of Sandwip, who was sitting in Salam’s office at that time, echoed him. “In my union, people have no such plant. A solar plant like this would have transformed the lives of people there.”

The highest off-grid solar use in the world

There are still many areas in Bangladesh today where extending the national grid is very unlikely in the foreseeable future because they are hard to reach. People residing in these remote locations must often pay very high rates for unreliable electricity from diesel-powered generators. Siddique Zobair, Joint Secretary of the Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority, believes that, despite a continuing reliance on coal power in the country, solar microgrid plants remain the best solution to provide affordable electricity in those areas.

“A solar microgrid provides electricity throughout the day and it can be used for commercial and industrial purpose. That changes the whole livelihood scenario of an area.”

"A solar microgrid provides electricity throughout the day and it can be used for commercial and industrial purpose. That changes the whole livelihood scenario of an area."

Bangladesh is now installing over 70,000 SHS per month, with over 3.8 million in total, under the national solar home program executed by the state-owned Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL). This is one of the most successful off-grid SHS programs, with the highest installation rate in the whole world.

After carrying out a survey in 2009 to collect information about a solar microgrid’s potential, Purobi Green Energy Limited chose Enam Nahar Market in the Muchapur Union of Sandwip as the plant’s location because of high electricity demand and the relative affluence there.

The rural market showed the most potential for solar microgrid application. However, the survey identified that the clustered households, especially adjacent to the market could also be the plant’s subscribers.

“As an investor of a new sector, we played it safe,” said Haque. “This area was familiar to us. We knew that the market and other commercial establishments here in Enam Nahar Market needed electricity and they were willing to pay for that.”

Solar changing lives in Kutubdia

Encouraged by the success of Sandwip’s pilot project, other entrepreneurs and investors are pursuing solar microgrid power plants in other remote areas of the country.

Mostaq Ahmmed, an expert in microfinance and social business and owner of Green Housing and Energy Limited decided to establish a 100 KW plant in Kutubdia, another island in the Bay of Bengal with 95,000 inhabitants.

Like Sandwip, the island of Kutubdia is separated from the mainland — speed boats or trawlers are the only travel options. However, residents of Kutubdia are not as rich as those of Sandwip; the island is dominated by commercial salt pans, which provide a meager source of income.

Ahmmed believed that establishing a plant here would be economically viable. “People need electricity everywhere. They know that electricity creates entrepreneurship and opens up new doors and they are willing to pay for it,” Ahmmed said.

His company established a 100 KW solar microgrid power plant with a four kilometre transmission line by the side of a large salt pan near Dhurong Bazaar in Kutubdia in November 2014. The establishment cost was Tk 6.3 crore (US$803,639) and the electricity price was fixed at Tk 30 (US 38 cents) per kilowatt hour.

Because of increased demand from the locals, the plan is to construct another 100 KW plant on land near the current site, said Ahmmed. “Obviously, electricity connections to commercial establishments are more profitable as they buy more electricity, but 50 per cent of the new plant’s electricity will be given to the household since they want it badly.”

A connection to the plant has allowed Abdur Rahim, a salt businessman, to open a coffee shop at Dhurong Bazaar. He operates a coffee machine, refrigerator and microwave, paying around Tk 10,000 to 12,000 (US$128 to $154) for electricity each month. He doesn’t mind paying because the shop is profitable.

“It only becomes possible because of the plant. Now many people including village leaders and government officials residing on the island come to my shop from a distance for coffee and snacks. This is the only coffee shop on the island,” Rahim said with a hint of pride in his voice.