Saskatchewan police may soon be subject to FOIP laws

Collaborative investigation between Maclean’s and Discourse Media drew attention to lack of racial policing data

Saskatchewan’s police departments may soon be subject to Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIP) legislation, mirroring policies already in place across Canada (with the exception of Prince Edward Island). The proposed changes to FOIP legislation were contained in a set of government-amended recommendations, which passed first reading in provincial legislature on June 13.

“It was time that it happened,” Gordon Wyant, Saskatchewan’s minister of justice, told a scrum of reporters the same day. When asked if police departments were pushing back against the change, Wyant said: “Most of them realized that there was going to come a point in time where they were going to be caught by our legislation. So they had been expecting it.”

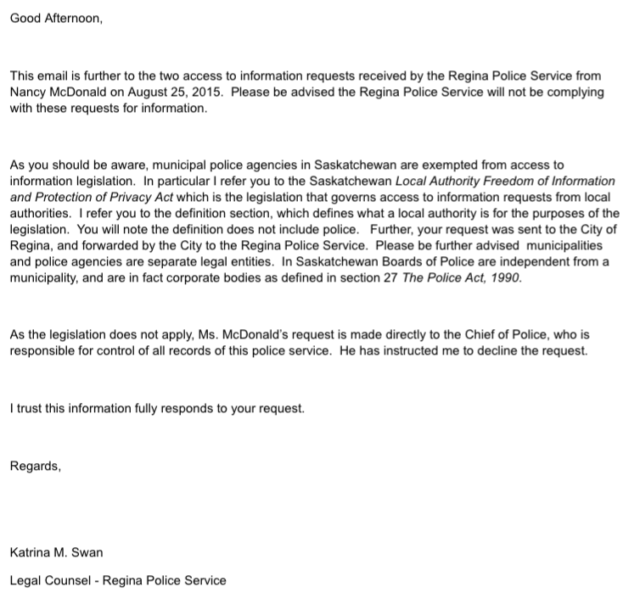

The change comes less than a year after a collaborative investigation between Maclean’s associate editor Nancy Macdonald and a team of reporters and data journalists at Discourse Media, which brought attention to a lack of racial data about policing. While conducting the months-long investigation, which revealed massive overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Canada’s prisons and provided evidence of racial profiling of Indigenous people by police, the Saskatchewan police refused to release racial data because they weren’t subject to FOIP legislation.

In light of the lack of publicly available data, Discourse Media conducted a survey to determine whether anecdotal reports of racial profiling were indicative of a systemic problem. The survey of over 850 students in Saskatoon, Regina and Winnipeg found that Indigenous students have greater odds of being stopped by police than non-Indigenous students, and staying away from illegal activity does not shield them from unwanted police attention.

Race affects perceptions of police

When asked for three words that describe police, Indigenous postsecondary students responded with words like "racist" and "scary" while others viewed police more positively.

What motivated the recommendations? Ron Kruzeniski, Saskatchewan’s information and privacy commissioner, proposed the recommendations to government last year. He’s pleased the amendments have now been tabled, since the legislation has not been updated in more than 20 years.

“When I first started preparing to take on this [role] two years ago, I thought police forces should be covered,” says Kruzeniski.

“An organization that receives tax dollars has immediately some obligations. And one obligation is access to records that they create, because it’s my taxpayer dollars that created those records.”

Will the legislation bring change to daily police practice? And what, specifically, will be tracked? Elizabeth Popowich, manager of public information and strategic communication for the Regina Police Service, says it’s not yet laid out, but will likely become more clear in the coming year.

“It may make some information more accessible to the public,” she says, adding that while the legislation has yet to become official, police already operate with transparency in mind.

“Even though we weren’t covered under FOIP legislation before, we’ve been aware of the rules and tried to pattern our public information after what’s already there,” says Popowich.

"Even though these small incremental changes within legislation are baby steps forward, I wouldn’t want people to get too comfortable, because police can still continue abusing their power on oppressed peoples."

When asked whether the new legislation could highlight racial profiling within the police force that previously went unsubstantiated, Popowich replied that police follow strict policy at all times. “We get a phone call and go to the incident. We don’t ask at the time of the call what a person’s ethnicity is.”

Popowich points away from the force: “We all, as a society, need to look at not just the justice system, but at the way our society as a whole deals with poverty and addictions and homelessness and mental health and education and employment — things that sooner or later manifest as crime.”

Andre Bear, a 21-year-old from Saskatoon, was featured in Macdonald’s Maclean’s story when his 18-year-old friend filmed the pair being stopped by police on their way home from baseball practice. When Bear asked the officer the reason they were stopped, he was told, “Shut up, passenger.”

“There’s so many times when I get racially profiled, and it’s terrifying to know that if I say the wrong thing to this white cop he can kill me, and there’s nothing that I or anyone else could ever do about it,” says Bear, who is stopped by police once every few months.

Bear, who is Saskatchewan’s regional representative for First Nations youth, says subjecting police to FOIP policy is a good thing. But he doesn’t want Indigenous people to correlate it with justice.

“I would like people to really instil in themselves … not to let down their guard. Because even though these small incremental changes within legislation are baby steps forward, I wouldn’t want people to get too comfortable, because police can still continue abusing their power on oppressed peoples,” says Bear.

“We can never give up, and we can’t give up on these officers because they’re people too. They’re just going with the same behaviours that society is perpetuating. We need a paradigm shift,” he says.

“Our country has been racist for so long.”