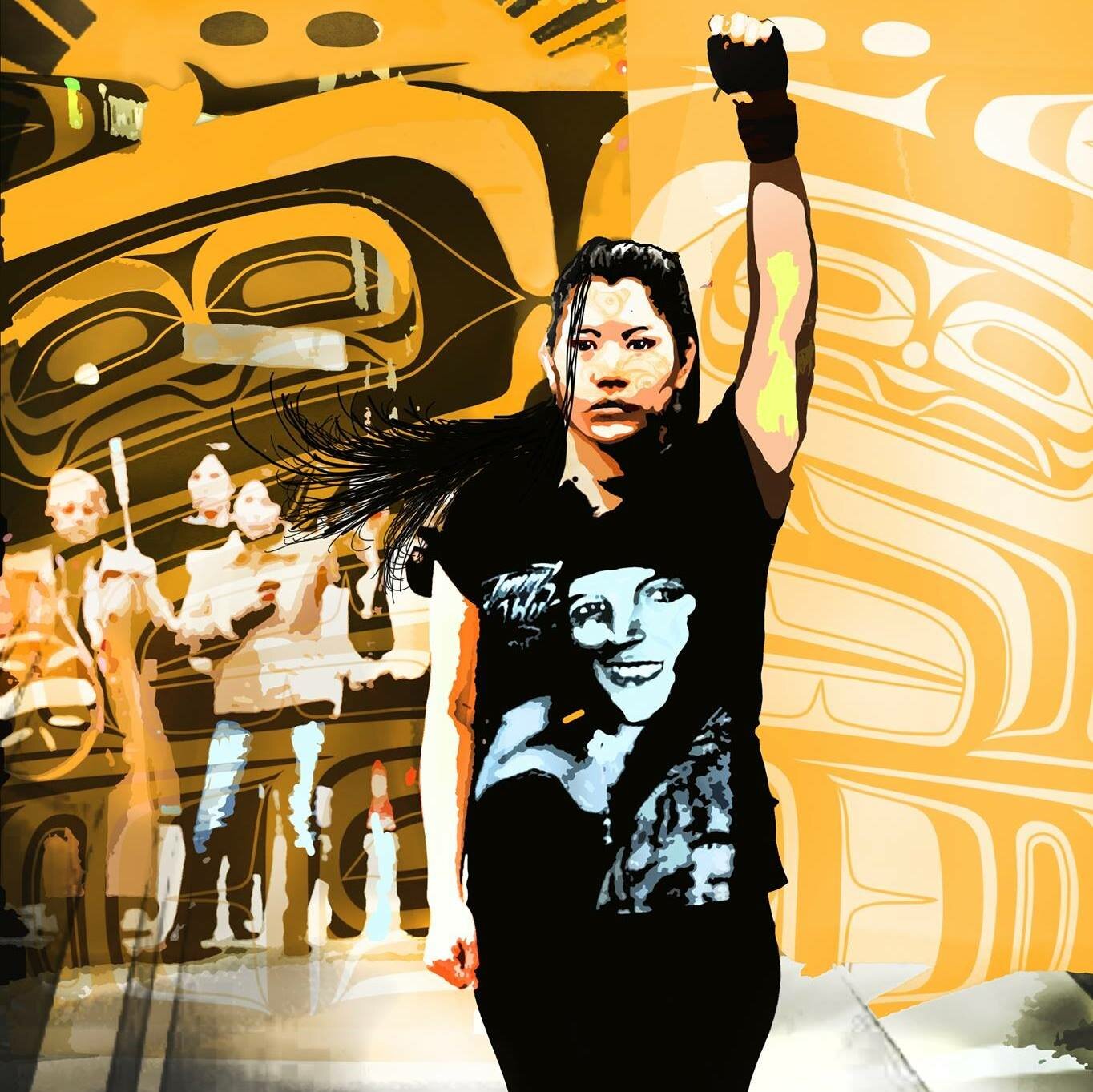

Indigenous activist Lorelei Williams on giving interviews: ‘I need to do a lot of self-care’

Williams, whose aunt and cousin went missing decades ago, has worked tirelessly to shed light on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

It’s been 40 years since Indigenous activist Lorelei Williams’ aunt, Belinda Williams, went missing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. And it’s been more than 20 since her cousin, Tanya Holyk, was reported missing (she was later identified as one of Robert Pickton’s victims).

That’s why Lorelei has worked tirelessly to shed light on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) over the years, granting interviews to more media outlets than she can count. Outside of this work, Lorelei is the women’s coordinator for the Vancouver Aboriginal Community Policing Centre, where she helps police build more respectful relationships with Indigenous women and families of MMIWG. The single mom of two kids also leads Butterflies in Spirit, a dance troupe that aims to raise awareness about MMIWG.

This is about Lorelei — not her story, but rather what it’s like to tell it.

Q&A with Lorelei Williams

Emma Jones: If you had to guess, how many interviews would you say you’ve done?

Lorelei Williams: Oh my God, I have never been asked that question! I honestly have no idea. Hundreds, for sure.

You’ve become a representative of a community. What does it feel like to be the go-to person for interviews about MMIWG?

It can be overwhelming at moments. Whenever I do any media work, it’s emotionally draining.

But at the same time, I just feel like my story needs to be told. And as emotionally draining as it is, as hard as it is on me, I just feel like the media’s listening to me for some reason and I don’t know why. The feelings that I get are nothing compared to what our Indigenous women and girls have gone through. I always think of my cousin and my aunt whenever I just feel like giving up.

I’ve had opportunities to speak to media from across the country, but being the go-to person has its downfalls. I’m just lucky that I have a lot of support in the community with my elders and with people in the community. That’s how I got there, with the support of the community.

I used to attend these rallies all the time. I’d go by myself or with a friend, and I’d be there, cry and then leave. Nobody knew who I was. Sometimes I feel like I wish it was that way again. But at the same time, people are actually listening to me, and I honestly don’t know where this voice came from. It just came.

I know that there have been days when you’ve done many interviews in a row, sharing very personal stories again and again. What did those experiences feel like?

I think the first time it was all day long was Dec. 8, 2015, when the inquiry [into MMIWG] actually came out.

That just happens to be Tanya’s birthday — my cousin who was murdered by Robert Pickton. The first time, I went home, I collapsed on my couch and I just burst into tears. I had to pick up my kids. It was my friend who got me through that one; he talked me through it and he was there for me.

Then, [there were] three days [I did media work] when the terms of reference were leaked. I did it and I woke up the next morning, and my whole body hurt — like, it ached. I couldn’t really move.

I felt like a zombie, going from one interview to another. I remember going from one press conference to CBC for an interview. Going from one place to the next, I was talking to people on the phone. I was actually eating and walking and talking with media.

What doesn’t the media “get” about reporting on Indigenous women’s stories? What should they know about people like you, who provide interviews?

They label our Indigenous women and girls as sex workers, drug addicts, drunks. This puts it out there that our women aren’t valuable. It makes them less valued, and nobody will care about them.

The media actually makes a lot of mistakes — the ones who don’t care. You can tell who’s there for a story and who actually cares. And the media who don’t care, they’re the ones who are making the mistakes. They’re putting in the wrong names, or the wrong age or wrong something. Whereas, there’s a few that actually take the time to sit down with the family members and get it right.

How do you take care of yourself during those times? What is self-care for you?

I need to do a lot of self-care, and I try to.

I have elders that I can go to, and I do as many ceremonies as I can get my hands on. I work with a lot of different women’s groups, so through that, I’m able to take advantage of the ceremonies. I feel like that’s helped me a lot. I do a lot of meditation, prayers, getting my nails done, baths. I do a lot of smudging. Anything that has to do with ceremony is very important.

I have to do that a lot because my work is intense. It takes its toll on me — it really does. I’ve been told by a few elders that I’m burnt out.

My daughter is 12 and my son is 8. One of my friends — she calls me a teleporter, actually. She asked me what my superpower was, and I didn’t know, and she was like, ‘You’re a teleporter!’ I was like, ‘What do you mean? Why are you saying that?’ And she said it was because I make it to every event. I honestly don’t know how I do it.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.