Can 21st-century journalism solve Canada’s 21st-century problems?

In a recent post for the Toronto Star, Ry Moran of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation asked, “What makes us Canadian?”

“From beer commercials to first-year political science classes, this question has echoed throughout much of our history. For many years, we carefully built the narrative that we are a peace-loving peoples — true, north, strong, and free. We are these things. I believe that. But we are also much, much more complicated than that,” he wrote.

“We are a country that has been denounced by senators, chief justices and former prime ministers as being genocidal in its treatment of Indigenous people. We are a country that ran residential schools for more than 150 years. Together, one year into the implementation of the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we are a country that is making promising gains, but still has much work to do in terms of righting past wrongs.”

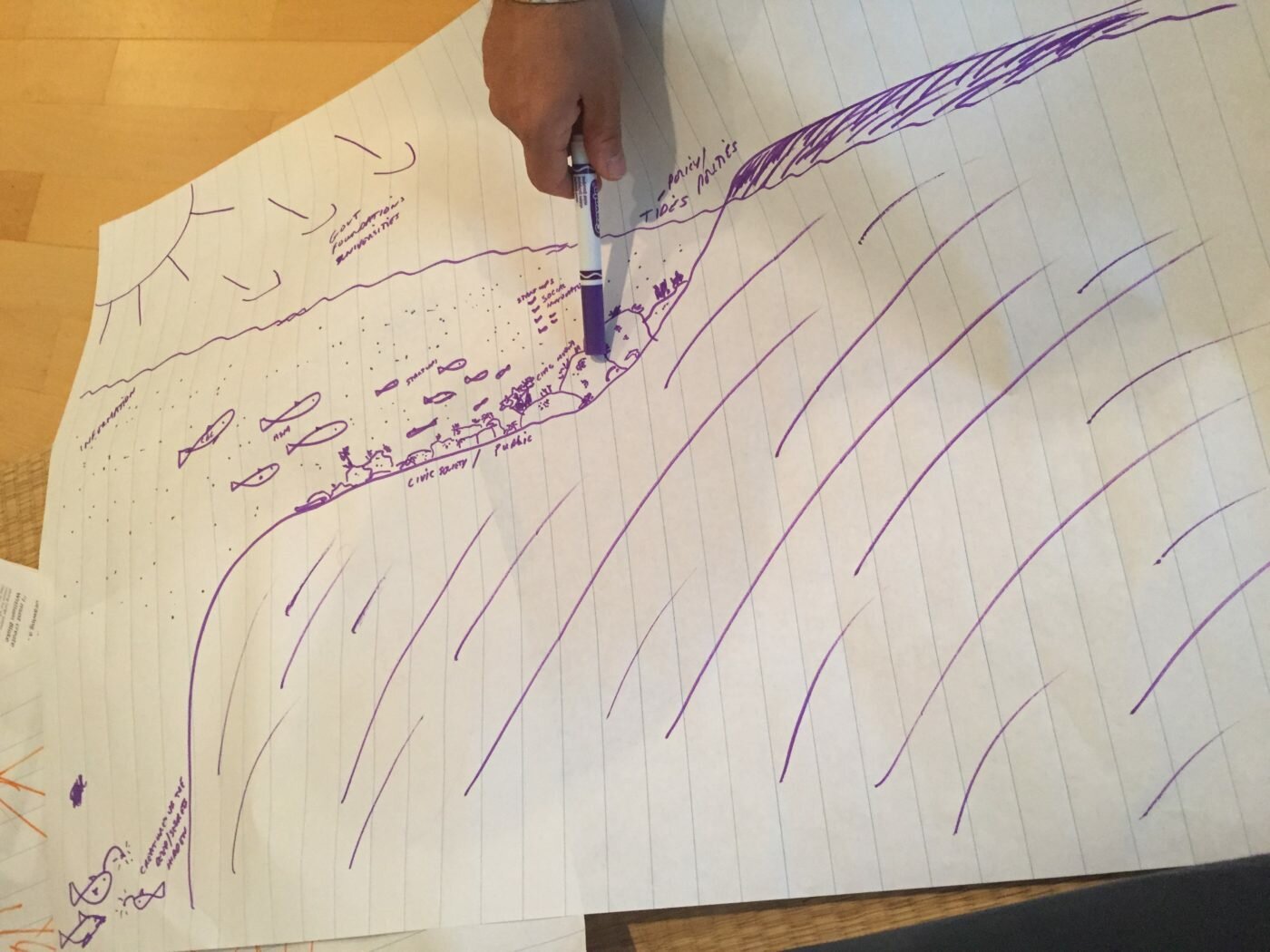

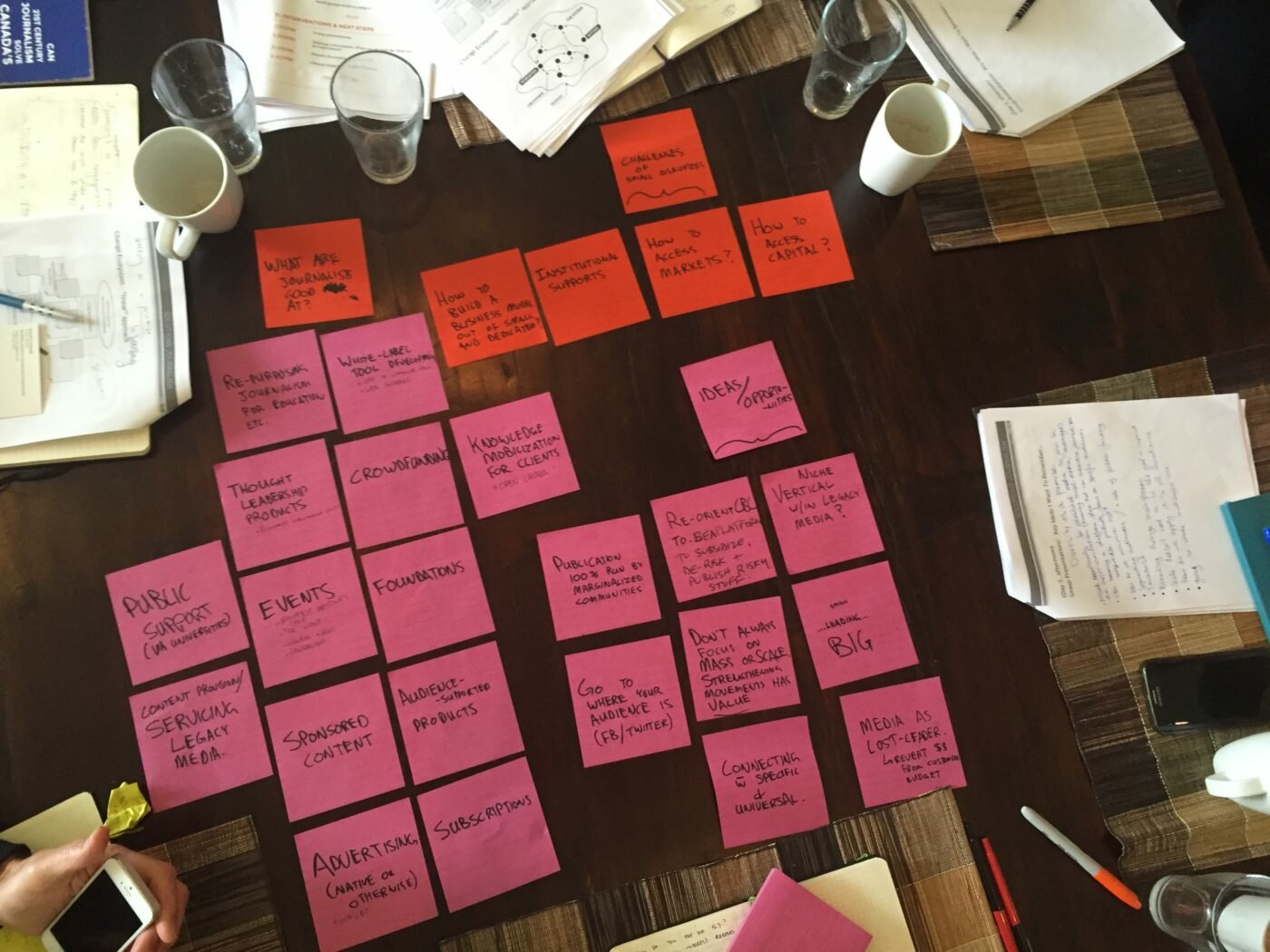

I read Moran’s piece while travelling home from a session at Wasan Island with a group of twenty-some participants involved in Canadian media in different ways, from small startups to legacy media organizations. Funded and organized by the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, I was privileged to be invited to incubate ideas around one (huge) question: “Can 21st-century journalism solve Canada’s 21st-century problems?”

As Canada aims to achieve reconciliation and build a national identity that includes all its people, we discussed how important it is to talk about the role the media plays in constructing our national narrative, and in telling the stories that inform the way we view ourselves as Canadians and in relation to those around us.

With this in mind, I’m coming away from Wasan Island with a deeper awareness that journalism has a responsibility to work towards reconciliation and social change in Canada. The problems faced by 21st-century Canada are complex and solutions themselves aren’t clear. At the same time, of course, the 21st-century journalism industry is facing complex challenges. And it’s so easy to get caught up in conversations around the crisis in the industry that we forget to ask how journalism can contribute to a better place.

But what if the two are connected? On Wasan, I was inspired by the idea that the instability of the media landscape might actually open up a space for innovation and problem-solving on a deeper level than was possible before.

Journalism, in its past and present forms, has really failed at telling the stories of all Canadians. Ian Gill, who will publish a new book about the Canadian media landscape, No News is Bad News: Canada’s Media Collapse – and What Comes Next, in September, made this point in a talk that opened the weekend. The Canadian journalism industry, he said, functions to support the colonial status quo. (Disclosure: Gill works for Discourse Media as a strategic advisor.)

“So much has gone unreported in Indigenous history,” said Gill. “There’s something disruptive about thinking about how to write with people whose truths have been inconvenient to the status quo,” Gill told us.

How can we do better?

So much work has to be done in order to create a media ecosystem that tells Canadian stories better, and many of these issues came up during our discussions. I left excited, though, because these challenges serve as opportunities to disrupt what we, as journalists, have established and assumed to be objective and adequate.

Underreporting in Indigenous and rural communities is one major hole that needs to be addressed. Another is the lack of diversity within the media itself. A different gap exists in the way we measure the life of a story. Often, we report on an issue and drop it before we write about how it got fixed.

David Bornstein, co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network (SJN) and author of the New York Times’ “Fixes” column, presented concrete ways to incorporate solutions journalism into our reporting practices. “Problems scream and solutions whisper,” he said. He meant that solutions stories can require deeper investigative work. But reporting on them can bring deeper knowledge to the public discourse around an issue, knowledge the public is hungry for and that SJN studies show can prove to increase engagement.

I’m a millennial with a fresh new journalism degree, so I can’t even imagine what working within a “stable” media landscape might look like (if that ever did exist), and I’m certainly not mourning the death of a golden age of journalism.

I’m excited to be entering the conversation now, because everything about the media is being questioned. Since storytelling and technology have crossed paths, more and more people have been using more tools to tell more stories than ever before. But I’m learning that within this exciting and rapidly changing framework, it’s important not just to consider the mediums we use to tell stories, but to evolve what we write and whose truths we tell.

As I saw this weekend, there’s a growing group of storytellers building a different media landscape. They’re using innovative models to represent Canada’s diversity, speak truth to power, deconstruct status quos and strive for impact. I’m really inspired by the potential for solutions that these models hold, both for redefining the journalism industry and for social change.