Will Canada become a big player in Africa's energy sector?

Reporter Richard Poplak checked out African Utility Week to explore Canada's connection on the continent.

If you’re interested in learning just how the world knits together, avoid reading think pieces and start attending big name conferences. Any conference will do, so long as there is a healthy mash-up of the public and private sectors in attendance: CEOs and ministers; actuarial scientists and policymakers; lobbyists and lobbyees.

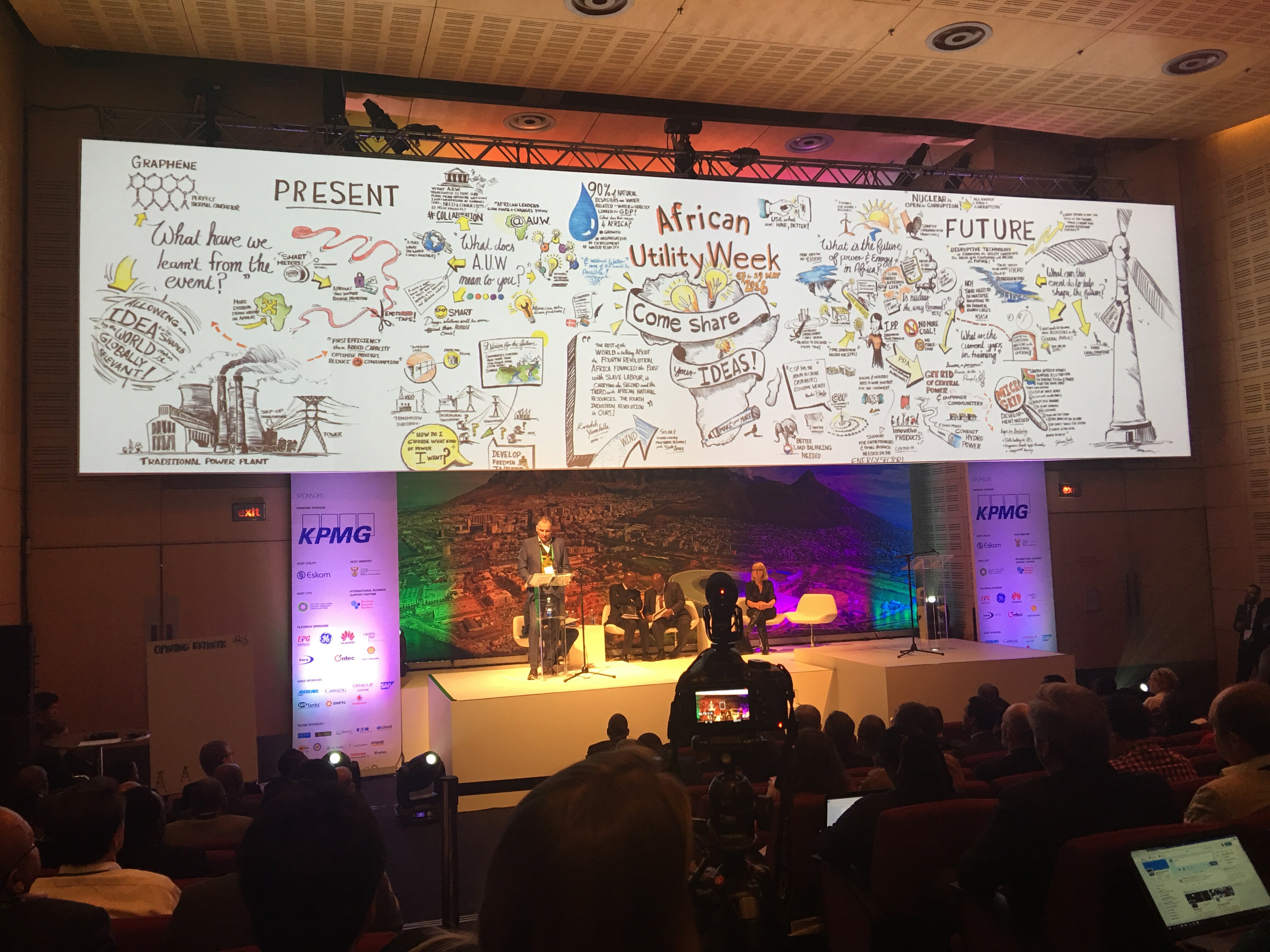

With this in mind, and considering that I’ve been investigating Canada’s role in energy access across sub-Saharan Africa, I decided to make my way to African Utility Week 2017. Earlier this month, the conference brought together 6,000 attendees with ties to the African electricity sector to the Cape Town International Convention Centre — a sun-dappled, if generic, behemoth located close to the city’s fabled waterfront. Basically, AUW assembles every big brand energy producing company worthy of the designation (General Electric, Shell, Tesla), along with aspirant smaller outfits, and representatives from dozens of countries, all interested in the burgeoning African power generation game. Canada was included in their number. Sort of.

Yes, the Canada booth displayed doodads that were impressive in their innovative simplicity. A woman named Hélène Soyer, a French lawyer with Quebec-based company ProBiosphere, was pitching a product called Archaea: it’s a bag of archaebacteria the size of a tea bag designed to purify 5,000 litres of water. It can, she said, treat pharmaceutical, petrochemical, food and other gruesome forms of waste, and costs only 300 rand, or $30 per kilogram—extraordinarily cost effective, even in Africa. There was a solar power initiative, a new transformer that I’m told is smaller and more handy than its forebears, and a fishbowl of full breath mints.

But there were none of the red carpet roll-outs that delegates experience at, say, a major mining conference. Cape Town’s largest and most notable such event is the Mining Indaba held every February, second only to Toronto’s Prospector’s and Developer’s Association of Canada (PDAC) conference as the mining industry’s most important annual set-to. At Mining Indaba, the Canadian booth is an international marvel, and on opening night the embassy hosts a drinks and hors d'oeuvres event that is very well attended.

And this is how conferences teach us about the world: Canada still links power production to the development initiated by mining and other resource sector-related mega projects. Power conferences, it seems, are an afterthought best left to massive multinationals, aspirant juniors, and the state-owned utility companies that oversee—often poorly—the vast bulk of Africa’s energy production.

As the conference unfolded, there were the usual commitments to growing energy production in Africa, and to increasing “partnerships” between states and private enterprise. The Americans made a weak pitch for their slow-moving Obama-era private/public PowerAfrica initiative.

Canada, as my reporting will make clear, hopes to become a significant player in emerging market energy production. But in many respects, Ottawa’s outlook seems very different—and in some ways opposed—to that of the countries it hopes to partner with. In South Africa, as in many African nations, the “developmental state” is the ideological engine of the future. Think China: strong state-owned enterprises that serve as “iron rice bowls,” providing the masses with both jobs and vital infrastructure in order to build a glorious tomorrow.

South Africa’s state-owned energy company emphasizes the shortcomings of this approach. Eskom was established as the Electricity Supply Commission by the pre-apartheid government in 1923, and during the apartheid regime procured a nuclear power plant, but mostly focused on driving the economy with coal (South Africa is one of the world’s major coal producers, and pioneered the technology of deriving liquid fuel from coke). Now, Eskom generates approximately 95 per cent of the electricity used in South Africa, and approximately 45 per cent of the electricity used in Africa. As one of the seven biggest power producers in the world, there were attempts to privatize elements of the company in the late 90s, but those proved to be unsuccessful. From 2008 to 2015, South Africa suffered from rolling brown-outs that were termed by local media as “loadshedding,” and which cost the country tens of billions of dollars in productivity.

While Eskom has successfully wrangled load shedding into the past, the utility has been beset by massive and successive corruption scandals. The Gupta family, a cabal of Indian businessmen with close ties to President Jacob Zuma, are said to have benefited massively from illegally awarded coal supply contracts, to say nothing of the fact that Eskom secured for them close to $60 million in bridge financing in order purchase a coal mine called Optimum from the Swiss-based multinational Glencore. Brian Molefe, the current CEO, has close ties with the Guptas, and was forced to resign from the company last year after the extent of their relationship was revealed in a report compiled by the corruption ombudsman. And yet, on May 15, after the Eskom board was unable to agree with the energy minister regarding Molefe’s roughly $3 million severance package, he was back in the office.

South Africans all but hit the roof. It’s an absurd scenario, and perhaps the highlight of the AUW was Molefe’s first scheduled appearance since his return to Eskom. But he didn’t show up—a wise move by any standards.

How does the government of Canada facilitate partnerships between an entity as dysfunctional as Eskom, and local companies looking to expand in Africa? It’s a difficult question to answer. Perhaps the worst blot on Eskom’s record is its pursuit of a nuclear power network allegedly to be built and partly funded by the Russians, a nearly $100 billion project that energy analysts insist South Africa doesn’t need. The potential for corruption is staggering, and some believe it would be unwise for any Western company to get involved in a deal that might fall afoul of international regulations.

These, then, are some of the challenges, and the truisms, that this year’s AUW laid painfully bare. Like most big name conferences, it articulated much about how the world actually works. Sadly, not all of it was flattering.