Government greenlights PNW LNG, but will the project be stopped?

Conditional approval sets the stage for a long legal fight over whether or not some First Nations groups were properly consulted and who can truly speak for the land.

The federal government’s approval of an $11-billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in northwestern B.C. could mean one of the largest infrastructure investments in Canadian history.

If the Pacific NorthWest LNG project moves ahead, it would mean a total capital investment of $36 billion and thousands of jobs. Many First Nations along the pipeline route have given their support in exchange for a share of those jobs, training and financial benefits. But some Indigenous groups, who say they were not properly consulted, are threatening legal action. This could bring the project to a halt — before it even starts.

In the hours leading up to the government’s announcement on Sept. 27, a group of First Nations calling themselves the Skeena Corridor Nations issued a release saying the project “does not meet the test” for respecting Indigenous rights and would be challenged in court.

They include the Gitanyow, Gitxsan, Wet’suwet’en, Lake Babine and Takla Lake nations, as well as the Allied Tribes of the Lax Kw’alaams, whose traditional territory includes Lelu Island, where the project will be located, near Prince Rupert.

During the announcement, Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna said, “From the very start, we engaged with the Indigenous communities that are right around the project. We provided funding [over $480,000] to enable them to participate in the project. We used traditional knowledge. There were concerns raised about the marine area and we took those concerns on board and we looked at ways that we could address them.”

But a hereditary chief of the Gitwilgyots, one of the allied tribes, suggests otherwise.

“Consultation has not taken place whatsoever,” said Don Wesley, S’mooygyet (head chief) Yahaan. “We’ll be filing a judicial review.”

Who needs to be consulted?

Petronas, the Malaysian-owned energy company with a majority stake in the Pacific NorthWest LNG project, has been engaging with local communities since 2012. They’ve conducted more than 3,000 meetings with First Nations and municipalities as well as 14 open house and information sessions. Petronas was not, however, mandated by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency to consult with Wesley or his tribe.

"The Tsimshian are a group of First Nations and some of them approve this and some don’t. It’s a messy situation."

The company instead consulted with five Tsimshian First Nation bands: the Metlakatla, Kitselas, Gitxaala, Kitsumkalum and Lax Kw’alaams. Four of these bands have signed term sheets that could lead to benefit agreements with the company, while Lax Kw’alaams band members recently voted in favor of continuing talks with Petronas, though concerns were raised about the polling process.

The bands in support are positioning themselves to receive potentially millions in financial payments as well as access to jobs and training opportunities for their members. Kitselas, for example, has a term sheet with Petronas, but also a project agreement with the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline project, owned by TransCanada, that would carry the gas approximately 900 kilometres from northeastern B.C. to the coast.

“Our agreement addresses the environmental and social safeguards we require in negotiations, as well as the delivery of economic, employment and educational benefits for our community. These core components mean substantial benefits for our community—now and in years to come,” said elected Chief Joe Bevan in a statement when the agreement was reached.

But Wesley says proper consultation needs to be done through the allied tribes, which represent the traditional hereditary governance system of the Tsimshian people.

“Elected band councils that have been negotiating with Petronas, the feds and the Clark administration only have jurisdiction on Indian Act reserves. Outside of that, it’s the tribe’s territory to govern,” he said.

"This isn't the end just because they approve it."

The conflict over who can actually speak for the territory has made it unclear as to who government and industry are supposed to consult with, says Gordon Christie, director of the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Legal Studies program. “There are a lot of complexities around this that really muddy the waters. The Tsimshian are a group of First Nations and some of them approve this and some don’t. It’s a messy situation.”

But that mess, says Christie, is to the advantage of the government.

“The best thing to happen would be a pause and some process for the people to decide amongst themselves who would be the people that talk to the Crown and industry. But the government benefits from having this fractured landscape. They want to press any of the people who are willing to say yes and say that they’re the ones who need to have consultation take place with.”

Discourse Media reached out to the Office of the Minister of Environment and Climate Change as well as Pacific NorthWest LNG. Neither made representatives available for comment before deadline.

Tribe members protest decision

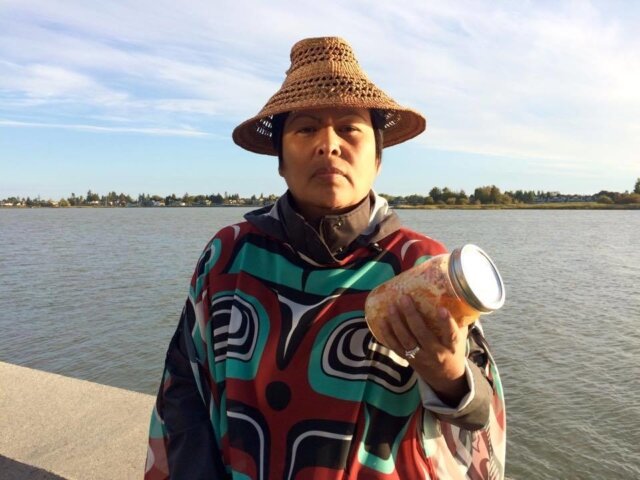

Members of Wesley’s Gitwilgyots tribe crashed the government’s announcement, bringing with them a jar of salmon to demonstrate what they feel is at stake at Lelu Island and the adjacent Flora Bank, the spawning grounds of the second largest salmon population in Canada.

“If they destroy our salmon, they destroy our people,” said Christine Smith-Martin. “It’s a sad, sad day for our community.”

While 190 legally binding conditions attached to Ottawa’s approval of the project are meant to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, environmental impacts on fish and fish habitat, and other concerns, Smith-Martin says Lelu Island could become the next Standing Rock if construction begins.

“That is the most sacred territory to our traditional Tsimshian people. We’re not going anywhere. We’re going to stay on that island,” she said.

“This isn’t the end just because they approve it.”

Upstream nations left out of consultation

Meanwhile, nations up the Skeena River are planning their own litigation. John Ridsdale is a hereditary chief of the Wet’suwet’en Nation. He says that even though they were not included in the environmental review process, because their traditional territory is not close to the terminal, their cultural practices are still at stake.

“Our salmon that go through the Skeena would be 100 per cent affected. We’re all salmon people. So we have a right to protect that,” he said.

He also wants those making the final investment decision to understand that the court case could take years to resolve. “Look at the record of the Wet’suwet’en. Last time we had a big court case it took 20 to 30 years and we won. So are they willing to sit on their money for that long?”

Petronas issued a statement on the day of the announcement saying they are pleased with Canada’s conditional approval. Along with their partners, they will now conduct a “total review” of the project before deciding on the next steps. A decision is not expected until 2017.

Litigation is expected in the coming weeks.