In First Nations, freedom of the press is unclear

Treaties are no guarantee of freedom of the press — but there’s little media coverage of First Nations anyway.

Once every quarter, during each of the year’s four seasons, 39 elected representatives from the Nisga’a First Nation gather to discuss everything from health and education to lands and resources of their nation. These 39 people make up the Wilp Si’ayuukhl Nisga’a, the legislature of the Nisga’a people of northern B.C.

Located in Gitlaxt'aamiks, the legislative building is architecturally styled after a traditional Nisga’a longhouse. Inside, it is anything but traditional. In the chamber, the wood paneling and plush red carpet hint more of the B.C. legislative buildings in Victoria than a longhouse. But this is Nisga’a country, and Nisga’a are very much in charge.

The Nisga’a are governing themselves under the terms of Canada’s first modern-day treaty, a hybrid democracy that melds contemporary and traditional laws. This past summer, as representatives of the Wilp Si’ayuukhl Nisga’a were preparing to gather in the Nass Valley, Discourse Media made a simple but uncommon request: “Can media attend?”

The answer was yes. But the question seldom gets asked. Only a handful of reporters have visited the Nisga’a legislature since the Nisga’a treaty was enacted 16 years ago. Freedom of the press applies in Nisga’a territory — it’s just that there’s hardly ever any press to apply it to.

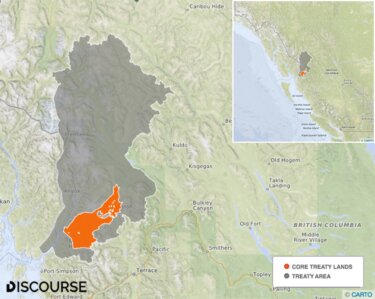

From Vancouver it’s about an hour’s flight to Terrace, B.C., and then another hour's drive north toward the snowcapped mountains of the Nass Ranges before arriving in Gitlaxt'aamiks, one of four Nisga’a villages and capital of the Nisga’a Nation. In the legislature, from a chair adorned with Nisga’a clan crests, the Speaker of the House guides elected representatives through their deliberations.

There are deep conversations about health care cutbacks, about the impact of property purchased adjacent to Nisga’a lands by foreign interests, about a renter eviction act. But unlike the B.C. legislature, where reporters constantly follow what’s happening, there is no press gallery documenting, dissecting and disseminating what transpires inside Wilp Si’ayuukhl Nisga’a. There is no one here to make sure the people who were elected by the public are accountable to them.

So why aren’t media following the Nisga’a legislature? There’s a combination of factors involved. First, there aren’t any trained local journalists. Outside the community, it’s not clear if journalists know they’re allowed to attend, even if they wanted to. Also, the economics of media companies and shifting patterns in their audiences are forcing outlets to close and others to downsize, leaving fewer reporters to cover more stories. For the Nisga’a — even now that they are governing themselves — their homeland, and the goings-on among the more than 7,000 people living in four small villages, are out of sight and out of mind to just about everyone.

“People aren’t aware of us. We’re so far removed from the large urban centres that have all the amenities and infrastructure required to provide that quality of life for people,” says Mitchell Stevens, former Nisga’a Lisims Government president.On Nov. 2, 2016, Eva Clayton beat Stevens to become president of the Nisga'a Lisims Government. Amenities, for example, like journalism.

The fallout

The lack of independent Nisga’a news coverage of critical issues was never more apparent than during the nation’s signing of a large energy access deal in 2014 — the Pacific NorthWest LNG project and the associated TransCanada Prince Rupert Gas Transmission project.

"We’re a young democracy and I’m convinced that launching Aboriginal Press will make the community stronger."

The Nisga’a government agreed to construction of approximately 85 kilometres of liquefied natural gas (LNG) pipeline on Nisga'a lands. Potential benefits to the Nisga’a include $6 million in cash, up to 300 jobs, property taxes, profit sharing and right-of-way payments. But 12 kilometres of the LNG pipeline would pass through Anhluut’ukwsim Laxmihl Angwinga’asanskwhl Nisga’a (Nisga’a Memorial Lava Bed Park), raising concerns about respecting the burial ground beneath it.

The Nisga’a government voted to redraw the jointly-managed park boundaries to accommodate the pipeline. A provincial government report shows the province passed a bill agreeing to the amendment in 2015.

Leading up to the deal, Nisga’a officials issued information on their website and in community newsletters, and held a special assembly as well as information meetings, including one in Vancouver in November 2014. They answered questions from mainstream media, but those stories for the most part focused on the economics of the deal.

The absence of any public discourse — before or after the decision was made — bothered Gitlaxt'aamiks member Noah Guno. He’s not sure local news coverage would have changed the outcome, but at least all sides to the issues could have been reported, and Nisga’a leaders might have been questioned much sooner.

The lack of stories about such a significant decision bothered Guno, 39, so he put together a small business plan. In March of this year he launched Aboriginal Press, an independent micro news site covering stories about Indigenous people and issues in northern B.C. Aboriginal Press’s Facebook page has more than 1,200 members.

The married father of three is a graphic designer by trade with no journalism training. Nisga’a consume news, but there is no real media culture, he says. Guno is unsure what he is legally allowed to report on, but despite all the obstacles, he believes the benefits of creating independent media where none currently exist outweigh the challenges.

“We’re a young democracy and I’m convinced that by doing this it will only help make [the community] stronger.”

Is freedom of the press a right?

Guno isn’t the only one confused about the rules around reporting in First Nations. Discourse has spent months researching this issue — contacting multiple lawyers, community governments and experts to ask how freedom of the press applies to First Nations. The short answer: it’s complicated.

The concept of freedom of the press is included in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Section 2(b) states that all Canadians have the right to “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.”

"Citizens get information and ask questions on issues. They can’t get that information without freedom of the press."

“[Freedom of the press] is an important part of freedom of expression,” says media lawyer Brian Rogers.

Rogers teaches media law at Ryerson University. A practising lawyer, he specializes in libel, privacy, copyright, freedom of expression and Internet-related law. He represents newspapers, magazines, book publishers and broadcasters. Rogers says freedom of the press gives citizens the right to gather information, participate in public processes, disseminate news and then act on it through debate and discussion. “The press is a surrogate for this for every citizen in society,” Rogers says.

The charter applies to all people in Canada, including Indigenous people, but there’s a catch. If you keep reading the charter you’ll get to Section 25, which says that “certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any Aboriginal, treaty or other rights and freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.”

The charter can’t infringe on Aboriginal or treaty rights. In the case of the Nisga’a, their treaty is silent on freedom of the press, so the charter applies. Former Lisims president Mitchell Stevens doesn’t contest that, but it’s also true that the Nisga’a government’s openness to the press has never really been tested by critical coverage.

Meanwhile, First Nations lawyer Judith Sayers disagrees that freedom of the press is automatically guaranteed after a treaty is signed. Sayers has dealt with media extensively as the chief councillor and chief treaty negotiator of the Hupacasath First Nation on Vancouver Island for 14 years.

According to Sayers, now an adjunct professor at the University of Victoria, matters that relate only to a First Nation — including their revenue, money coming from corporations and agreeing to project benefit packages — are for band members to know, not journalists. “Journalists cannot cover band meetings. They are internal matters of the First Nation,” says Sayers.

Rogers notes that there are precedents for freedom of the press not necessarily equating to press access. “There are circumstances accepted by courts where cabinet requires a certain degree of confidentiality,” he says.

Sayers says one of the rights recognized by Section 35 of the charter is a First Nation’s right to determine who resides on their lands and who can come onto their lands. “A band council and members can say no to [the press],” she says. In other words, while treaties theoretically enshrine freedom of the press by default, treaty nations can refuse journalists who are not band members access to Aboriginal lands — an effective veto over freedom of the press.

Rogers believes Aboriginal people in a treaty nation “would want, need and rely upon freedom of expression just like anyone else in our society. All the same reasons that there is public access to other kinds of public bodies should apply when it comes to band council meetings.”

But in practice, that seems to not always be the case. Sayers says reporters can call tribal officials to inquire about meeting outcomes afterwards, and band members are free to speak to the media. In other words, the press isn’t completely cut off from covering band affairs. But is a band council legally allowed to say no to a journalist?

It’s hard to say for sure, and it seems likely to remain a grey area because no one has challenged it. The issue just isn’t a priority with governments, First Nations or media, Rogers says. He believes there’s only one way to find out what would happen if a reporter tried to attend and document a meeting that a band considered closed. If the council turned a reporter away, the matter could end up being tested in court.

“Clearly there would have to be a court case that a judge would help clarify,” Rogers says. “That’s one way. Not the best way, but that’s one way.” All society benefits when public scrutiny is brought to bear on public officials in public institutions, Rogers says. “Citizens get information and ask questions on issues. They can’t get that information without freedom of the press,” he says. “You raise this because this is missing and there hasn’t been sufficient scrutiny.”

All roads lead to Facebook

With all the confusion around freedom of the press, combined with a lack of coverage, Nisga’a people aren’t waiting for a case to go before the courts.

In Vancouver, Ginger Gosnell-Myers watched the LNG issue closely. A Lower Mainland-based Nisga’a citizen from Gitlaxt'aamiks, Gosnell-Myers has lived away from home since her teens.

But she maintains close ties to her ancestral home, adding that issues in the Nass still affect the more than 5,000 Nisga’a who live away from home. Getting information from home about issues such as LNG was a challenge, she says.

“Our ability to know about these plans and to organize as a people to protest was only possible because of social media,” Gosnell-Myers said. “We will not stand idly by while they [the Nisga’a Lisims Government] hold secret meetings for secret deals that trade our protected lands for whatever it was they happened to gain from it.”

Gosnell-Myers took issue with what she felt was a lack of transparency by the Nisga’a Lisims Government, so she did something about it. She started a Facebook group in 2013 called Nisga’a Democracy and Governance. The group’s members can post questions, air their concerns and share thoughts about Nisga’a government issues. Before the group was established, information sharing was informal. Something more was needed. “I felt that Nisga’a have always been a vocal and politically savvy population, but that we did not have a mechanism or space to share or say what was needed,” she says.

When she started her Facebook page, the Nisga’a treaty was more than a decade old, but democratic participation wasn’t keeping pace, Gosnell-Myers says. Community engagement and communications lagged, and there weren’t meaningful options for citizens to participate in governance beyond voting every four years. The Facebook group acts as an equalizer. “Social media gives us the tools to rectify that and create space and discussion amongst ourselves, and to continue the Nisga’a tradition of fighting for our voices to be heard,” she says.

The Nisga’a government isn’t the only new First Nation democracy facing questions about independent media covering its affairs.

More such hybrid democracies are set to be created across the province. The Tsawwassen and Maa-nulth First Nations have negotiated their own treaties through the B.C. Treaty Commission and have their own legislatures. The commission’s website shows there are 59 other B.C. First Nations at various stages of treaty negotiations.

As new treaties are signed and nations move to full self-government, freedom of the press — at least on paper — will be part of their new democracies.

"I felt that Nisga’a have always been a vocal and politically savvy population, but that we did not have a mechanism or space to share or say what was needed."

Meanwhile, while the Nisga’a Democracy and Governance Facebook group doesn’t practise journalism, at more than 1,400 members the group’s size shows an appetite for information and accountability — something people aren’t going to wait for conventional journalism to provide.

“Until the Nisga’a Lisims Government can design ways for the people to be engaged and updated and informed on important matters, groups like Nisga’a Democracy and Governance will fill that gap,” Gosnell-Myers said.

While Noah Guno seemed positioned to fill that gap, circumstances have changed. Guno was elected to the Gitlaxt'aamiks Village Government council on Nov. 2, 2016. At 272 votes, Guno received the highest number of votes of the seven winning candidates.

Guno says he found it too hard to continue making a living as a reporter. Being a village councillor frees his time up to pursue better-paying work, but also to say something as a public official about things he saw while he was a reporter.

Guno says he’s thought through the issue of conflict of interest with his role as owner-reporter of Aboriginal Press and his position of village councillor. He’ll still own the press and will work on growing the business side of it, but he has relinquished all editorial responsibility and hired two writers to file stories instead. When pressed about the perceived conflict, he says, “I’m going to honour the oath I swear to office. But if this comes up, then I’ll follow the letter of our village government policy.”

Guno says he’ll continue to work for change, just in a different venue. “When doors open for you, you have to be there to grab hold and open them,” he says.

This is the first article in a five-part investigation into freedom of the press in First Nations. Read the whole series:

1. In First Nations, freedom of the press is unclear

Treaties are no guarantee of freedom of the press — but there’s little media coverage in First Nations anyway.

Thirty-five stories that are unlikely to ever see the light of day.

3. FOI laws don’t apply to most First Nations

Only a handful of more than 600 First Nations in Canada have laws that grant their members and the public access to information.

4. The freedom to limit freedom of the press

Some Indigenous band councils are banning journalists, challenging freedom of the press guaranteed by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Are they protecting their communities from harm, or protecting themselves from scrutiny?

First Nations community members are pushing for post-treaty freedom of the press — but a lack of journalism training opportunities is holding back those trying to hold their governments to account.