Can universities lead the movement toward reconciliation?

Possible Canadas

What do you want Canada to be? This is the question 10 student journalists posed to their campus communities. They interviewed hundreds of students on 10 campuses, then produced in-depth investigations into how Canada could start to realize these visions. What did they learn? That despite all the stereotypes of disengaged millennials, young people have a lot to say about the future of our country. Explore the 10-part series from the Possible Canadas fellowship about how we, as a country, can get to that future.

Billy-Ray Belcourt smelled mustard when he opened the door to the University of Alberta's Aboriginal Student Council (ASC) office on Oct. 5, 2015.

Somebody had graffitied the lounge’s walls with a spray of mustard and barbecue sauce over the weekend. Saddened, Belcourt, the president of the ASC, wrote a mournful Facebook status the same day, reading: “Like our bodies, spaces for Indigenous people are violable.”

This was the second time an Aboriginal space had been vandalized on the University of Alberta campus within a year. In March, sacred teepee poles were draped with toilet paper just days after the university erected them as a memorial display honouring missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Belcourt says racism has been a common thread throughout his four years at the university. It has sometimes been overt, including racist comments posted onto the University of Alberta Confessions Facebook page.

These incidences weren’t easy to shake off, Belcourt says, noting that it felt “weird” to be in the lounge following the vandalism.

“These things aren’t coincidental, they aren’t random, they aren’t by chance,” he says. “These are two of the most public markers of Indigenous people’s presence on campus, so what does that mean when they’re being vandalized?”

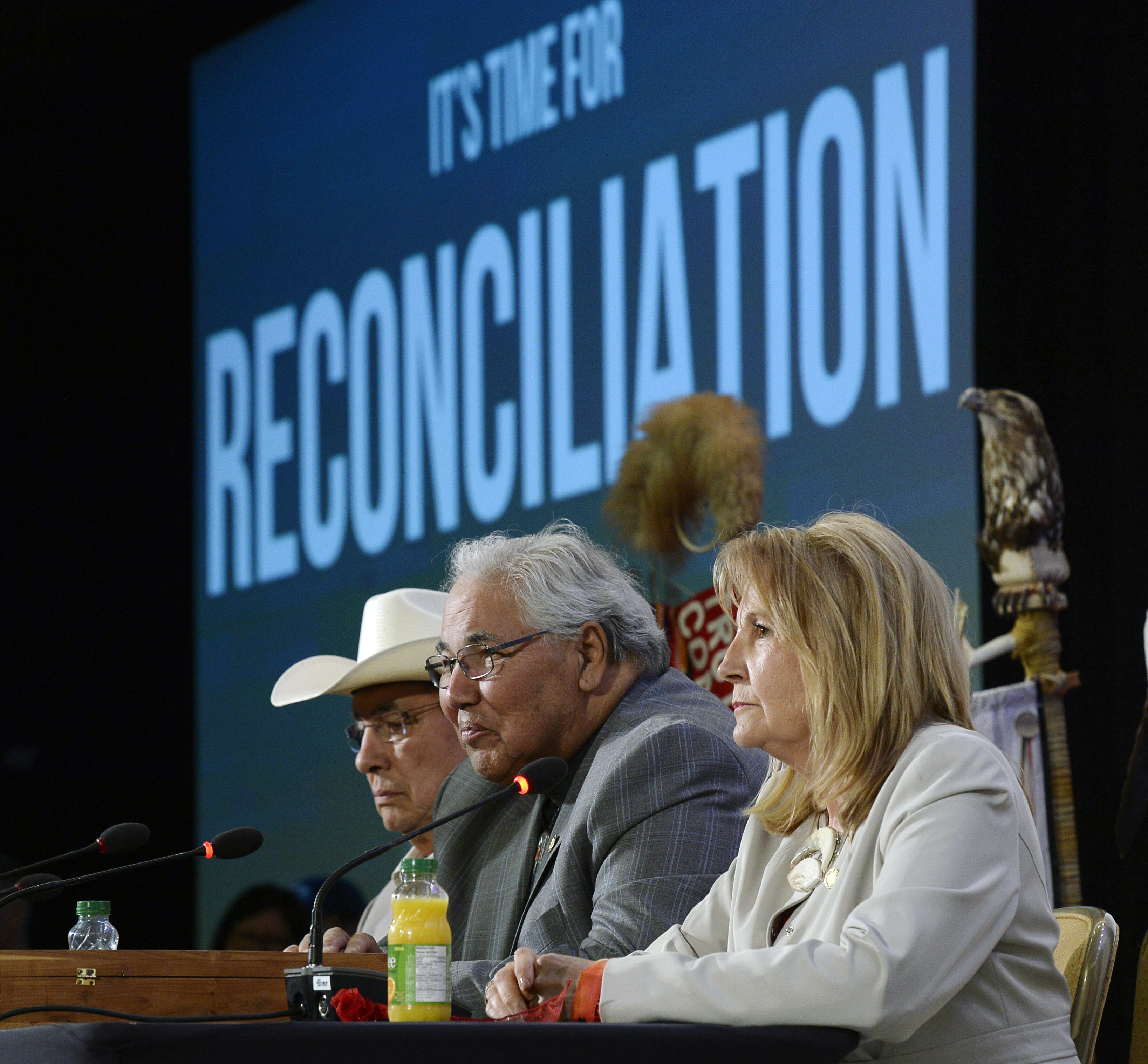

Canadian universities are key in shaping the views and priorities of future generations. So it’s not surprising that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) acknowledged the significance of universities in their final report released this summer. Of their94 calls to action,In June, the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission released 94 “calls to action” to “redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.”

The scope of recommendations range from child welfare to education to Indigenous language rights, and has recommendations targeted for private and public spheres of Canadian life alike. The document calls upon law schools in Canada to require all students to take a course in Aboriginal people and the law, for example. Notably, the document calls upon the federal government to appoint a public inquiry into the causes of, and remedies for, the disproportionate victimization of Aboriginal women and girls.

The 11-page document can be read here.

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf four were specifically targeted toward post-secondary institutions, including calls for universities to offer degree and diploma programs in Indigenous languages and to instruct education students on integrating Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms.

But Belcourt’s experience highlights a major roadblock in this path to reconciliation. When Indigenous people are discriminated against on campus, it’s clear that the education most students are getting today still isn’t enough to combat prejudice.

It begs the question: what would it look like for Canadian universities to become genuine hubs of intercultural understanding and empathy? How could Canada harness the power of so many young minds gathered on campuses across the country to support true reconciliation?

It starts in school

When the TRC was established in 2008, it aimed to inform all Canadians about what happened in residential schools by documenting the experience of survivors, families, communities and anyone personally affected by the residential school experience.

The TRC created a vividly detailed historical record of the legacy of the residential school system,From 1870 to 1996, more than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were placed in residential schools and forbidden to speak their language and practice their culture. The TRC estimates there are 80,000 former students living today, and that the ongoing impact of residential schools are a major contributor to challenges facing modern Aboriginal populations.

Canada’s TRC is one of many commissions worldwide to undertake revealing and resolving past wrongdoings, mostly by governments. Other examples include:

South Africa

In 1996, President Nelson Mandela authorized a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to study the effects of apartheid in South Africa. The commission allowed victims of human rights violations to give statements about their experiences, but also allowed perpetrators of violence to request amnesty from criminal prosecution.

Argentina

The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons, initiated in 1983, investigated human rights violations, including 30,000 forced disappearances, committed during the Dirty War.

Guatemala

The Historical Clarification Commission was created in 1994 in an effort to reconcile Guatemala after a 36-year civil war. The commission issued a report in 1999 which estimated that more 200,000 people were killed or disappeared as a result of the conflict. along with an extensive report with calls to action about how to pursue reconciliation, including several about the education system. It also established a permanent national research centre on these issues, hosted at the University of Manitoba.

“Consider what it means, what we’re talking about today: the enormity of it,” TRC commissioner Marie Wilson said on the day the report was released. “Parents who had their children ripped out of their arms, taken to a distant and unknown place, never to be seen again, buried in an unmarked grave long ago forgotten and overgrown. Think of that. Bear that. Imagine that.”

Yet despite this, still today residential schools are largely absent from most elementary and high school curricula. The hole in Canada’s public education system is so gaping that Justice Murray Sinclair, head of the TRC, went as far as to tell provincial education ministers in 2012 that they were not just ignoring history, but repeating it.

“We reminded them the very same message that was being taught in residential schools was the very same message being given in the public schools of this country,” said Sinclair in an interview with CBC. “We told them to change the way they teach about Aboriginal people, to ensure all children going into public schools learn what the government did to young Aboriginal children for 130 years.”

A CBC News survey found that while most Canadian students are exposed to “some lessons on the topic of residential schools throughout their public education, teaching on residential schools is not mandatory across the country.

In Manitoba, treaty and residential schools education is mandatory for students in middle and high school. But in Alberta, for example, learning about residential schools is not necessary until Grade 10. In Quebec, no mandatory courses require focusing on residential schools, although teachers are allowed to cover the topic.

One challenge for teachers is a lack of curricular resources.

“Up until now, there really hasn’t been access to resources and source documents [that are accurate],” Charlene Bearhead, TRC education coordinator, told the CBC. “Right now, you can go across the country and you’ll find pockets of teachers that are teaching about residential schools because they’ve done that on their own, but there hasn’t been commitment by ministries of education.”

Universities also suffer

The same problem exists in Canadian universities. Undergraduates have mandatory required courses in subjects such as English and biology. That is starting to change. In November 2015, the University of Winnipeg senate voted to become the first university in Canada to implement a mandatory Indigenous course for all undergraduate students. Lakehead University is following suit with a similar program to start in 2016. In 2006, the University of Alberta established the first standalone Faculty of Native Studies in North America, and it remains the only one of its kind — though students are not required to enrol in its courses.

Universities find themselves in a unique bind when dealing with Indigenous issues, says Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and founder of the University of Alberta’s First Nations Children’s Action Research and Education Service.

In her research, Blackstock has not found evidence of a single university standing up to residential schools at the time they were operating. Universities played a significant role in training teachers, priests and politicians who worked in residential schools and supporting their policies, as was outlined in the University of Manitoba’s 2011 official statement of apology and reconciliation to residential school survivors.

“Many institutions had a direct or indirect hand in perpetuating the misguided and failed system of assimilation that was at the heart of the Indian Residential School system. The University of Manitoba educated and mentored individuals who became clergy, teachers, social workers, civil servants and politicians. They carried out assimilation policies aimed at the Aboriginal peoples of Manitoba,” the apology reads. “Today the University of Manitoba adds our voice to the apologies expressed by political and religious leaders and so graciously accepted by survivors, Aboriginal leaders and Elders.”

According to the TRC, the University of Manitoba is the only university in Canada that has apologized for its role in educating the operators of residential schools.

“Here in Canada, there was an opportunity to say what happened in those schools is something that you’d never want to happen to a child in your family. But sadly, the discriminatory attitudes of those schools are still alive in today’s society,” Blackstock says.

The future of education

Some provinces are making strides to include the history of residential schools in their curricula. In 2014, Alberta announced that all kindergarten to Grade 12 curricula will include mandatory content on the significance of residential schools and First Nations treaties. Manitoba and British Columbia made similar announcements that provincial curricula will now require teaching students about the legacy of residential schools.

Once these students graduate high school, Blackstock says universities will have to change in order to accommodate the new generation of students who have been taught the histories of residential schools in their public schooling. Just like many students today would likely protest if their universities taught blatantly homophobic material, Blackstock envisions a time in the near future when simply presenting Indigenous knowledge as supplementary to European histories or relegating Aboriginal perspectives to sparse optional courses and brief explanations in textbooks will not be enough.

“I want to raise a generation who are not only equipped with this information but are equipped with peaceful and respectful ways of co-creating a different type of Canada. I think that’s the real game of reconciliation,” she says.

The power of peers

But co-creating this future Canada requires more than just new textbooks and courses.

The Canadian Roots Exchange (CRE) has a vision for what else it can look like, and how young Indigenous and non-Indigenous people can work to build a new way of educating future generations — together. Through workshops, conferences and multi-week exchanges to Indigenous communities, the program brings together Indigenous and non-Indigenous people under 29 years old to promote cultural understanding and reconciliation. Now in their seventh year of operation, CRE has engaged close to 3,500 youth.

The organization was awarded the Diversity, Equity & Inclusivity Award for Service & Innovation from the York Region Community Inclusivity Equity Council, and one of the co-founders, Dr. Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux, was named an honorary witness of the TRC.

Emily Lennon, 25, graduated from McGill University in 2014. She’s a non-Indigenous Canadian and says the program was transformative. Lennon says that the Aboriginal history she learned growing up in Alberta “was kind of divisive, and, frankly, not really true.”

Lennon recalls learning in high school that First Nations communities were benevolent to European fur traders, for example. It wasn’t until she became involved with CRE that she learned that Indigenous peoples were also exploited by them.

In 2012, Lennon was a youth leader in CRE’s Youth Reconciliation Initiative in Montreal, where she worked as a facilitator. The group organized workshops and events for youth in the Montreal area, including Study in Action, a grassroots undergraduate and community research conference at Concordia University.

Joining CRE was part of a bigger process of “trying to relearn Canadian history” for Lennon, and credits it with opening doors to many other experiences for her. Following her participation in CRE, she was hired as an intern at the Native Friendship Centre in Montreal.

“It was beautiful seeing these bridges being built and these gaps being closed,” she says. “It taught me to unlearn what I learned in school growing up.”

Justin Wiebe, a member of the CRE board of directors and former participant of the program, says that as a Métis person, he feels it often falls on him and other Indigenous people to “carry that weight of educating everyone.” CRE, he says, equips non-Indigenous youth to educate others as well. It also affords Indigenous youth the chance to learn about other Indigenous cultures that are not their own.

Wiebe isn’t sure if there is an “endgame” to reconciliation, or if there should be. But building relationships through CRE is the start of what he says is bound to be a long process — one that he believes hasn’t quite started yet in Canada.

“The reality is that most non-Indigenous people are able to live their lives without creating meaningful relationships with non-Indigenous people,” says Wiebe. “When you know someone, you’re more likely to do something about the issues we see.”

Vibhor Garg, executive director of CRE, says that reconciliation must start with youth.

“The younger generation can do something different and they want to do something different. So here’s an opportunity for them to come together in a respectful way and understand each other,” he says. “We believe youth have the power to change the way Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples interact with each other in Canada.”

Despite the apparent success of CRE, there are few comparable peer-to-peer programs for youth in Canada, either within the school or university systems or outside them.

There are other peer-to-peer reconciliation programs to learn from across the globe. The 12-day UN Youth Australia Aotearoa Leadership Tour immerses youth in travel across New Zealand and Australia to experience Indigenous culture and connect with community groups. Participants are given a chance to analyze how governments, NGOs and the private sector attempt to achieve reconciliation with Indigenous peoples in the region. They also discuss colonialism within the context of the nations they visit and on a global scale. The tour culminates in Sydney, Australia, where they are encouraged to engage with and critique Australian policies on Indigenous issues.

In the United States, the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation works on extensive projects throughout communities across Mississippi to foster cultural understanding between different racial groups.

Since 2010, it has hosted the Summer Youth Institute — a nine-day residential program with 30 students from across the state that’s free of charge for all who participate. The group hopes to facilitate community activism and civic engagement by teaching participants about the civil rights movement and giving them training in leadership and critical thinking.

Students design projects for their home communities and the Summer Youth Institute helps to implement them. One African-American participant, for example, worked with the William Winter Institute to build a community garden in the front lawn of her grandmother’s house in an all-white neighbourhood in Jackson, Miss.

“They never got to know their neighbours,” says April Grayson, community building coordinator at the Summer Youth Institute. “It was a standoffish kind of place … [the project] brought a cohesiveness to the neighbourhood that had never been there before. That was a real effort to cross racial lines that helped the neighbourhood flourish.”

The William Winter Institute also facilitates the Welcome Table, an 18-month process for communities divided by racism focused on reconciliation. It has three phases: monthly meetings with all stakeholders focused on relationship- and trust-building capped by a weekend retreat, training in structural racism, implicit biases and microaggressions, and developing and implementing an “equity plan” for the community. “[Participants] look at structures in their community that might promote inequities, and develop strategies to help address them,” Grayson said.

While the work of reconciliation in Mississippi is vastly different from the reconciliation needed across Canada, programs like the Welcome Table and the Summer Youth Institute present a model of peer-to-peer engagement that has demonstrated impressive impact. Of those who attend Welcome Table retreats, 84 per cent leave believing that racial reconciliation is an important issue. And a whopping 88 per cent of those who attended the retreat found that they reconsidered their position on race. The racial demographics for the Welcome Table are evenly split: half the participants are black and half are white.

Taking root

Along with larger institutional changes, which can be slow-moving or daunting to navigate, taking lessons from peer-to-peer organizations like these may offer a glimpse of how universities can make quicker progress on supporting reconciliation in Canada. But it may require all types of university organizations to rethink how they work.

For example, last year, Belcourt met with students' union executives at the University of Alberta to suggest implementing a position for an Indigenous student councillor position on the students' council. He hasn’t seen any action on the initiative yet, he says, and feels that “oftentimes my suggestions or initiatives or policies are deemed radical or too drastic to implement that they would have to change the structure that’s been used,” he says. “There’s this bureaucratic maze I find myself in that I can’t get out of.”

University of Alberta students’ union president Navneet Khinda met with Belcourt last year when she was the students' union's external vice-president to discuss the possibility of an Indigenous councillor position. She says that while there is “nothing inherently wrong” with having an Indigenous student councillor position, it would not fit within their current model of governance.

The students' council is currently modelled on “representation by faculty,” meaning each of the university’s faculties is represented by a number of councillors proportionate to their student population (the Faculty of Arts, for example, has six councillors and the Faculty of Business has two). Having “interest-based” positions, she says, would warrant a larger change to the council’s structure.

“I do think that more Indigenous students can and should be involved in students' union governance though, and perhaps there are specific tools and methods of engagement which we can use to reach out to more students,” Khinda wrote in an email, adding that while different from what Belcourt has suggested, the Faculty of Native Studies’ councillor position has remained unfilled this year.

The University of Alberta declined to comment on what the institution is doing specifically to address reconciliation.

Belcourt hopes that in the last semester of his degree he can make a difference. Belcourt is working to develop an Indigenous student life committee this January to work with university student leaders and staff to develop initiatives at the institutional level.

“Indigenous students need to be heard. We need to be taken seriously. We can contribute to these kinds of discussions,” he says.

Belcourt believes reconciliation requires more than just Indigenous people resolving generations of trauma stemming from residential schools; it requires non-Indigenous people also grappling with the discrimination that has continued since the schools closed, and that may mean taking a hard look at structures and institutions, including universities.

“I think when we talk about decolonization, often non-Indigenous people recognize it as us saying ‘we don’t want you here.’

“But actually, decolonization, for myself at least, is imagining a future where we don’t always resort to violence just to live, a space in which Indigenous peoples can flourish and not just merely survive the present.”

Possible Canadas is a partnership of diverse organizations that share the goal of supporting forward-looking conversations about the future of Canada. The project is produced by Discourse Media and Reos Partners, in collaboration with RECODE and the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. Partners’ support does not imply endorsement of the views represented.