How do we change who we’re really voting for?

Strategic voting was a key part of the last federal election campaign. The new government has promised to reform the electoral system. What does a fairer, more representative electoral system look like?

Possible Canadas

What do you want Canada to be? This is the question 10 student journalists posed to their campus communities. They interviewed hundreds of students on 10 campuses, then produced in-depth investigations into how Canada could start to realize these visions. What did they learn? That despite all the stereotypes of disengaged millennials, young people have a lot to say about the future of our country. Explore the 10-part series from the Possible Canadas fellowship about how we, as a country, can get to that future.

At the beginning of the most recent federal election campaign, the New Democratic Party (NDP), Liberals and Conservatives were in a tight three-way race with no clear winner. Pollsters predicted the NDP would come out ahead with a minority government. Instead, the Liberals won a surprisingly comfortable majority with 184 seats in the House of Commons.

Even longtime NDP incumbents were voted out in favour of Liberal candidates, suggesting a desire from left-leaning Canadians to overthrow the Conservative government. Better safe, many voters seemed to think, than sorry.

Strategic voting efforts this past election showed that Canadians wanted to change governments. But what the election also demonstrated, for many, was the need for another kind of electoral system that enables Canadians to vote for a party they truly support and a House of Commons that is representative of what the populace wants.

The problem with first-past-the-post

Our current electoral system, known as first-past-the-post (FPTP) or “winner takes all,” is one in which voters cast one ballot in their riding, or electoral district, and whoever gets the most votes wins that riding’s seat as a Member of Parliament. That means that a candidate can win a riding and become the area’s representative even if they get less than a majority (50 per cent) of the vote.

In “The case for electoral reform in Canada,” Prof. Werner Antweiler of the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business provides readers with an analysis of FPTP in Canada and different electoral systems in other countries. He says that FPTP has worked well for Canada because historically, we’ve only had two main parties. But now, our political landscape is more diverse and we need a voting system to reflect that reality.

“The consolations are basically hindering smaller parties from being heard and that’s really the design of the first-past-the-post system,” says Antweiler. “It’s giving a huge boost to the big parties and basically gives smaller parties very little ability to find representation.”

Take the 41st federal election, in 2011, where the Conservatives won a majority government of 166 seats with just 39.6 per cent of the vote. When taking the percentage of NDP votes (30.6 per cent) and combining it with those for the Liberals (18.9 per cent), Bloc Québécois (6 per cent), Green party (3.9 per cent) seats and others (1 per cent), 60.4 per cent of Canadians did not want the Conservatives in power.

This election, voters seemed determined to not let it happen again.

Mount Royal University student Jennifer McDonald, who lives in Calgary, considers herself an NDP supporter, yet knew that the NDP candidate in her riding didn’t stand a chance against her riding’s Conservative incumbent (and former prime minister) Stephen Harper. McDonald says “desperate Googling” for advice on how to make her voice count let her to strategicvoting.ca.

Strategicvoting.ca is a platform that launched in 2008 to help Canadians determine who to vote for in order to “increase the number of seats won by progressive parties (Liberals, NDP and Green),” and avoid the problem of splitting votes between candidates on the left.

According to founder Hisham Abdel-Rahman, the site had had 800,000 visitors this election period. He promises to keep the site up and running until electoral reform happens.

“As long as we have first-past-the-post,” says Abdel-Rahman, “there will always be a need for strategic voting.”

There are other organizations intent on changing our electoral system altogether. Vote Pair, a website dedicated to “hacking the vote for democratic change," was formed during the federal election in 2008 to bring attention to electoral reform. Fair Vote Canada, another campaign for electoral reform, strives to produce voting system reform for all levels of government. Both want an electoral system that more fully represents the population as well as focuses on local candidates.

The advocacy organization Leadnow launched their Vote Together campaign in the most recent federal election. Targeted specifically at voters keen to oust the Conservative government, Vote Together asked voters in 29 swing ridings across Canada to support the NDP, Liberal or Green candidate they recommended based on their own polling data. Though the campaign was not without controversy, it seemed to have the intended result. Their recommended candidate won in 24 out of the 29 swing ridings that they targeted.

Anthony Sayers, professor of political science at the University of Calgary, believes that it’s not uncommon for these movements and the desire for electoral change to arise when a party has held power for a long period of time. According to Sayers, Canadians are thinking “maybe making the system more responsive and not overweighting it for the largest party would be a good thing.”

The options

One of the alternatives Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is considering is creating a system based on proportional representation (PR).

Central to this system is the idea that the number of seats gained by a political party should be proportional to the number of votes they acquire nationally. So, if 20 per cent of the Canadian electorate votes for a party, then that party will receive 20 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons. Depending on how this system is structured, it would eliminate the need for strategic voting.

But according to Sayers, this system must take into account the size of the electorate and how big or small parties should be before they get representation.

Because Canada is “too big and diverse a country,” says Sayers, “we would most likely use a system of proportional representation based on province-wide constituencies.” This means that the government would have to convene a discussion about how many seats each new provincial constituency would be entitled to. Which, Sayers says, has the potential to create friction between provinces.

This system would ensure all governments, except in rare circumstances, would be coalitions. Theoretically, this would alleviate some of the strict partisanship of Parliament and encourage free debate. But it is likely that backroom deals would still be necessary for parties to ensure the 50 per cent plus one requirement needed to pass bills in Parliament.

If Canada were to adopt a proportional representation electoral structure, it’s likely we would go with one of two voting methods within this structure: mixed member proportional representation (MMP) or single transferable voting (STV).

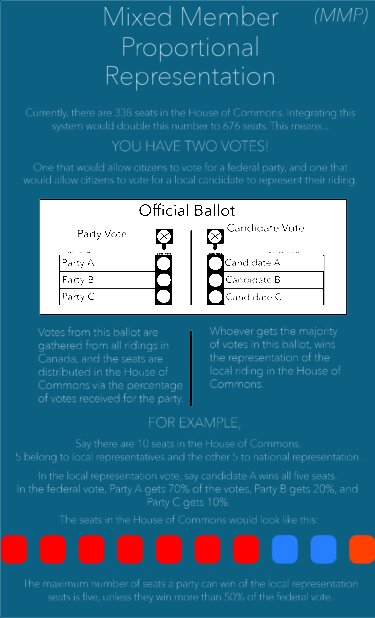

In MMP, voters get two ballots come election day and the number of seats in the House of Commons is doubled. Similar to our current system, the first ballot would allow citizens to choose a local candidate to represent their riding. Whoever gets the majority of the votes for this ballot would win the representation of that local riding, ensuring local representation in the House of Commons.

The second ballot would allow citizens to vote for a federal party, and this vote would decide the number of seats each party would have in the House of Commons. The number of seats given to each province or district would likely be relative to its population size. Candidates would be chosen from a party list that establishes the candidates in the order the party wants them to be elected.

For example, say there are ten seats in Parliament for MPs, five of which belong to local representatives and the other five to national representatives. In the first ballot, candidates from Party A win all five local seats by having the most votes. They will, therefore, get a minimum of five seats. In the second ballot that is based on the proportion of votes overall, Party A gets 70 per cent of votes, Party B gets 20 per cent, and Party C gets 10 per cent. Using this data, two more seats would go to Party A, two seats would go to Party B and one would be claimed by Party C.

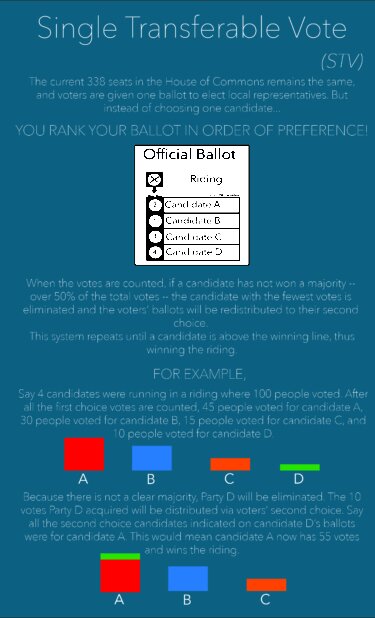

STV is the electoral system which, according to some experts, is most plausible for Canada. In the STV electoral system, voters are given one ballot to elect local representatives – similar to the ballots we currently use. The only difference is that voters rank candidates in order of preference.

When the votes are counted and a candidate is not above the majority line, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. The corresponding voters’ ballots will be redistributed to their second choice. Therefore, citizens get to have their votes count toward another candidate if their first choice doesn’t win. This system repeats until a candidate is above the winning line, thus winning the riding.

For example, let’s say four candidates were running in a riding where 100 people voted. After all the first choice votes are counted, 45 people voted for Party A, 30 people voted for Party B, 15 people voted for Party C and 10 voted for Party D. Because there is not a clear majority, Party D will be eliminated and the party’s 10 votes will be distributed according to the voters’ second choice. If all of the second choice candidates indicated on Party D’s ballots were for Party A, it would now have 55 votes and it would win the riding.

What’s next?

Canada would have to systemically change the electoral system to allocate for more seats in Parliament using the MMP system — something that would be very costly. Moreover, in order to implement any of these systems, Canadians would need to educate themselves on the new system.

So far, three provinces — British Columbia, Ontario, and Prince Edward Island — have attempted to reform their provincial electoral systems, but these attempts were struck down in referendum votes. Both Quebec and New Brunswick have investigated and proposed new electoral systems, but no effort has been made to hold a referendum.

Sayers points out that once a government has power, it’s rare for them to change electoral laws “unless they think they will benefit from them.”

Nonetheless, any change could have a significant impact on our democratic institutions. Reforming the ways MPs are elected will reshape the political landscape, shifting the way that politicians campaign and eventually legislate, as well as the way they are elected. With the recent federal election having the highest voter turnout in decades, however, Canadians are making some of those changes themselves.

Possible Canadas is a partnership of diverse organizations that share the goal of supporting forward-looking conversations about the future of Canada. The project is produced by Discourse Media and Reos Partners, in collaboration with RECODE and the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. Partners’ support does not imply endorsement of the views represented.