Here's why people are still questioning BC Liberals' review of Site C

Politicians wanted to avoid tough questions about need for project, future costs, critics say.

Why is the biggest megaproject in B.C. history, the $8.8-billion Site C dam, going ahead without the standard review by the B.C. Utilities Commission to determine if it’s actually needed and makes economic sense?

That’s one of the key questions readers raised when we announced our series diving deep into Site C.

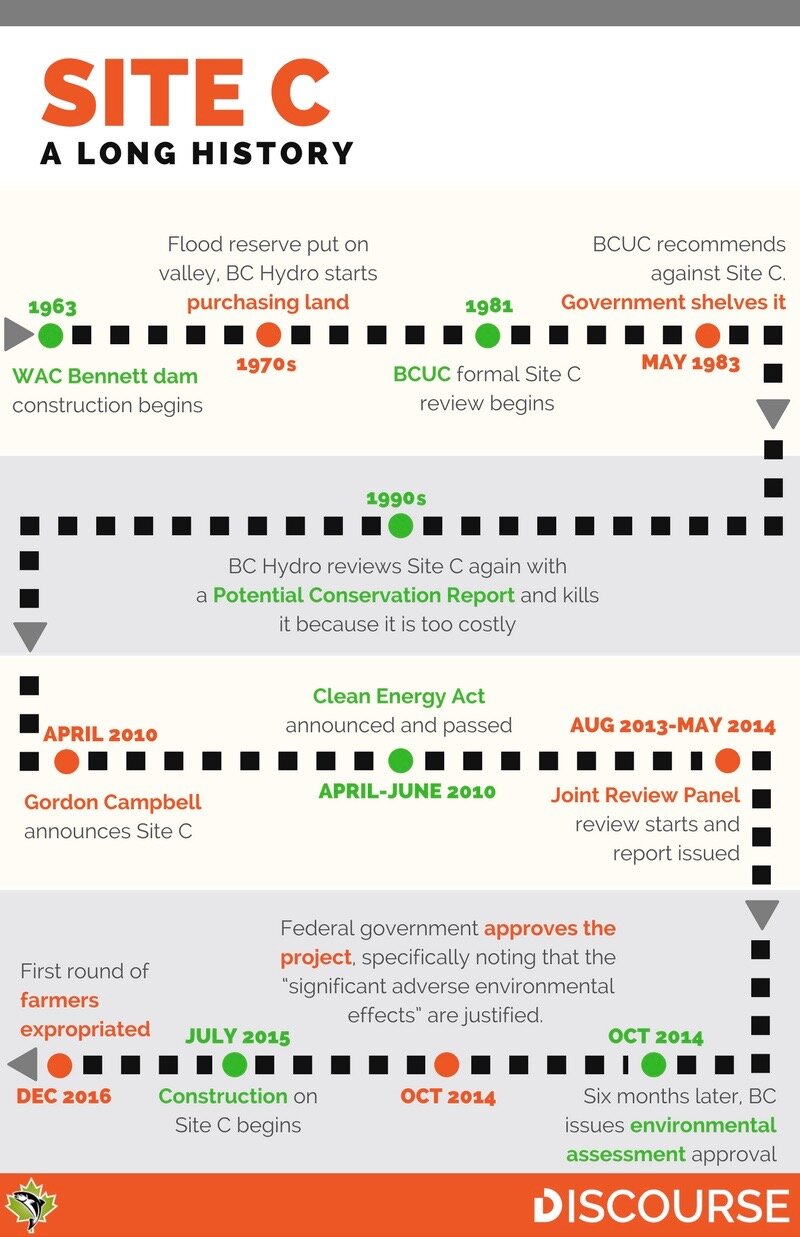

The utilities commission has been reviewing major projects like Site C for 37 years. It was established in 1980 by former premier Bill Bennett.

Bennett created the BCUC to provide independent oversight of BC Hydro and other utilities. It reviews business plans, holds hearings with expert witnesses and approves — or rejects — rate increases and plans for new dams or transmission lines. In part, the commission was established to prevent politicians from meddling in the operations of utilities — things like keeping rates low before an election, or demanding certain projects go ahead based on political considerations.

Commissioners are appointed by government, but are independent of it. It has been said by government officials that the BCUC’s job is to “protect us from ourselves.” The commission’s mandate is to keep rates fair and to make sure capital investments get a reasonable return.

One of the first reviews the BCUC did was of Site C, when it was formally proposed in 1981. The commission spent two years reviewing the project and ultimately recommended it be rejected. BC Hydro’s forecasts for future electricity demand were too high, the commission found, and the dam wasn’t needed. (One consideration the BCUC weighs is that building unnecessary projects means higher electricity rates for consumers.) Bennett's Social Credit government accepted this recommendation and shelved the dam.

What changed?

The tide began to turn against independent review and regulation when then-premier Gordon Campbell launched a Green Energy Advisory Task Force in 2009 to create a strategy to develop B.C.’s power potential. Its recommendations included building more big power projects to make BC Hydro a net exporter of electricity — and it called for a rejig of regulatory oversight.

The Clean Energy Act legislation that followed in 2010 turned these recommendations into law. BC Hydro was directed to become self-sufficient, able to generate enough electricity to meet all the province’s power needs (and eventually much more). That’s unusual for a public utility that is hooked into the North American grid, which allows companies to buy electricity to meet peak demand periods — something BC Hydro does regularly.

The legislation specifically exempted Site C and other projects from BCUC review and gave decision-making power to the government. Vancouver Sun columnist Vaughn Palmer called it “a historic power grab by the premier and his ministers.”

Liberal Premier Christy Clark's Energy Minister Bill Bennett (no relation to the former premier) has said large decisions like Site C are so influential they amount to policymaking, and therefore should be made by elected officials, not independent commissioners.

Still, there's no reason the BCUC couldn't have played a role in Site C. The legislation establishing the commission allows it to perform a variety of functions, from approving or rejecting projects to conducting public reviews. For instance the Social Credit government asked in 1981 for a review of Site C, not a decision. Based on that review and recommendation, the government — politicians —decided to reject the project.

This time around, the Liberal government could have referred Site C to the commission to review if the dam is needed and what its effects on electricity rates would be — a review that would have left in the hands of politicians the final decision as to whether to proceed.

Instead, Site C was reviewed by an independent Joint Review Panel, appointed by the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency and the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office to consider environmental impacts. The panel was also asked to review concerns of First Nations and to consider the economics of the project, but it lacked time and staff to evaluate these issues. A BCUC review could have been far more comprehensive.

Then vs. now

The 1981 BCUC review took over two years to complete, with hearings where experts and members of the public could pose questions — questions that had to be answered.

The BCUC had the staff to digest the reams of paper submitted as evidence as the commission reviewed supply and demand data, project finances, physical design, environmental, cultural and economic impacts and First Nations considerations.

In contrast, the Joint Review Panel was conducted over a period of nine months, with just a handful of staff. The panel was limited to reviewing the environmental, social and First Nations impacts. The panel stretched its review to give some attention to whether the project was needed at all, and to look at possible alternatives. (This section was criticized by the federal and provincial environmental assessment offices as being “outside the scope of the panel’s mandate.”)

The Joint Review Panel’s limited scope meant it did not make a final project decision, expecting its recommendations to be used to guide further evaluation.

And what did it recommend? Well, the panel urged that Site C be reviewed by the BCUC, which would have the capacity to evaluate the project’s economics.

“We won’t be doing that,” said Bill Bennett, the energy minister.

Harry Swain chaired the Joint Review Panel, and argues this was the wrong move.

"In the past, two significant adverse effects were enough to stop a project. So we have a new record."

“The government exempted the project from consideration by the BCUC and also by the Agricultural Land Commission, on the rationale that the panel was doing all the work and this would be merely duplicates,” Swain said. “But the panel had very limited resource and very limited time, and frankly just didn’t have the time to examine, for example, the capital costs for reasonableness.”

During its assessment, the Joint Review Panel reviewed submissions from experts and the public, which outlined a large number of significant adverse environmental effects, many irreversible.

The environmental assessment agencies — the government agencies with power to issue or deny permits — approved the project, saying the environmental damage was “justified in the circumstances.” Details of how this was determined were not made public.

A statement by more than 370 scholars and scientists said the decision to go ahead with the dam marked an “unprecedented imposition of numerous significant adverse environmental effects.”

Swain says the large number of environmental concerns should have been enough to cause the dam to be rejected.

“In the past, two significant adverse effects were enough to stop a project. So we have a new record,” he says. Since the 2014 Joint Panel Review report was released, he has become an unequivocal opponent of the dam, saying the costs — financial, environmental and social — far outweigh the potential benefits to British Columbians. “The risk of this dam is enormous. And it’s all yours.”

The BC Liberals continue to defend their decision to bypass BCUC review, saying enough reviews have been done, including a review of project costs by accounting firm KPMG. An Energy Ministry representative said, “Site C is the most reviewed BC Hydro project in history.”

(The ministry statement also said, “No other major hydroelectric dam project in the past required BCUC approval.” That is true, but only because work on the last dam to be built, Revelstoke, was started two years before the BCUC was created.)

Why did the government approach it this way?

Former BC Hydro deputy CEO Beverly Van Ruyven, who retired in 2011, says the government likely wanted to retain control of decisions about the dam.

“This project is so big, it’s a once in a career opportunity for a political person,” she said. The government likely wasn’t certain about Site C when it brought in the Clean Energy Act, she said.

“But they wanted to review the evidence and make the decision. Not the utilities commission.”

Critics say the government and BC Hydro wanted to avoid a BCUC review because they feared their projections and risk assessments wouldn’t stand up to scrutiny.

“I think that’s probably true,” said Richard McCandless, a former senior manager in the government. “That’s why I’m saying [Site C] shouldn’t go ahead. It doesn’t have the right cost-benefit. It’s just going to saddle everybody with debt for years to come.”

Ontario lawyer and energy policy expert George Vegh says independent oversight protects the public from short-term political decisions.

Governments are attracted to big energy projects in part because the costs are pushed into the future and come in the form of bigger electricity bills.

“So the government is virtually always in the position of developing ambitious plans with costs for which they are unaccountable,” Vegh wrote in a recent commentary on the Ontario energy market.

Many groups, including the Union of B.C. Municipalities, are still calling for a comprehensive BCUC review of Site C.

The BC Liberals have consistently refused.

With the provincial election due on May 9, NDP leader John Horgan has said that if elected he would send Site C for review by the utilities commission.

Green leader Andrew Weaver, who was at Campbell’s announcement of the dam in 2010 and said it qualified as green energy, now opposes the dam.

This story is part of collaborative investigation project by The Tyee and Discourse Media. Read reporter Zoë Ducklow's introduction piece here. Read about whether or not Site C is past the point of no return here.