Powering self-determination at Kanaka Bar

A community without oil, gas or forestry development potential looks to renewable energy to become self-sufficient.

The reserve lands of the Kanaka Bar Indian Band — one of 15 communities that make up the Nlaka’pamux Nation — are located on a lonely stretch of highway 250 kilometres northeast of Vancouver, in a hinterland where no mainstream industries exist. There’s no mining industry, no oil and gas development, and no forestry work to be done.

Yet, over the next five years, this tiny community in the Fraser Canyon is planning to become completely self-sufficient. They want to generate their own energy, grow their own food, provide community members with employment and be completely financially independent. All of this could be possible because what Kanaka Bar lacks in resources, it has in energy: solar, wind and more hydro than the 65 people living on reserve could ever use themselves. (There are over 200 registered band members in total, two thirds of whom live off reserve).

A critical point in the band’s modern history came in December 2013 with the completion of the 49.9-megawatt Kwoiek Creek run-of-river power project, which resulted in a 40-year agreement to sell electricity to BC Hydro. With ownership of clean energy — in this case the 50 per cent stake the band holds in this hydro project — comes power.

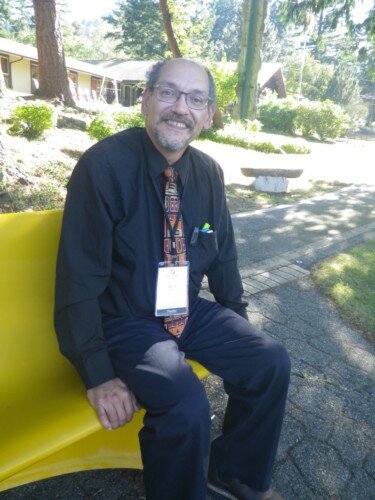

“We never said we wanted off the grid,” says Kanaka Bar Indian Band Chief Patrick Michell, a lawyer who left his practice to work full time on the hydro project in 2005 and became chief in spring 2015. “We just wanted to take ourselves off the grid.”

Today, Kanaka Bar generates revenue from the sale of hydro power to the BC Hydro grid. It also recently completed two solar energy projects (a six-kilowatt ground solar unit and a four-kilowatt pillar solar unit) that reduce daily demand for electricity from the grid to two reserve buildings by as much as 50 per cent. As more energy projects are developed and come online — including more solar, plans for wind, and a new one-megawatt hydro project (the latter operational by 2018) — the community will be increasingly immune to BC Hydro rate increases that are crippling many other small communities across B.C.

“As we get familiar and acquainted with the technology, the plan is to [expand] current projects, plus install new energy projects, with the goal of becoming 100 per cent energy-self-sufficient,” says Michell.

At Kanaka Bar, clean energy is reversing the effects of colonization.

The motivation to develop clean energy at Kanaka Bar, in the works since the late 1970s, has always been about ensuring community self-reliance. Back in early 2012, after their hydro project had advanced past the point of no return, the band engaged its membership on and off reserve and started planning for the future. First came a land-use plan, which included a vision of Kanaka Bar as a “self-sufficient, sustainable and vibrant community,” reflecting the community’s conviction that climate change was real and self-reliance was an imperative. Energy was the beginning, but the planning was and remains about survival.

By next year, at least one greenhouse will be in operation, using biomass (wood) in the winter to grow tomatoes and other food staples. Then, like with their clean energy, Kanaka Bar hopes to learn from that first greenhouse and scale up production, with a vision to develop aquaponics, a closed-loop approach that grows tilapia and recirculates the fish waste to fertilize plants. “So when we put gardens in, why are we doing it? To create employment? No. To create a food-self-sufficient community. There [will be] no import and export market in 40 to 60 years, which means we’re not going to be eating California raisins, we’re going to be eating Kanaka Bar raisins.”

The band predicts a doubling of its reserve population over the next five years. Many band members are already being drawn home by the promise of jobs and self-sufficiency, says Michell. The current 18 houses on reserve will expand to at least 36. When that time comes, the band expects 100 per cent of the membership will be employed on reserve.

Michell is now mentoring other First Nations that want to emulate Kanaka Bar’s success. “Clean energy powers self-determination,” he recently told a group of First Nations community leaders from across Canada assembled on Bowen Island, B.C., all working to develop clean energy projects of their own. “At Kanaka Bar, clean energy is reversing the adverse effects of colonization.”

Such effects include a disconnection from language, culture and, perhaps most importantly, the land. This in turn led to the destruction of family bonds and endemic community violence. “These adverse effects took 150 years to get here, [so] it will take a little while to pull it all out,” says Michell. “But something is happening at Kanaka Bar, and the only industry, the only sector, is renewables. The question now is: can this work somewhere else?”

Christopher Pollon reported for Discourse Media at a 20/20 Catalysts Program event on Bowen Island, B.C. He will be contributing ongoing reporting on energy access in Indigenous communities.