Why telling a grey story matters

Continuing to make the case for sustained, nuanced coverage of systemic issues

Like most media organizations, Discourse Media is rooted in a core belief that access to nuanced information is an essential attribute of a functioning democracy and a driving force for social impact.

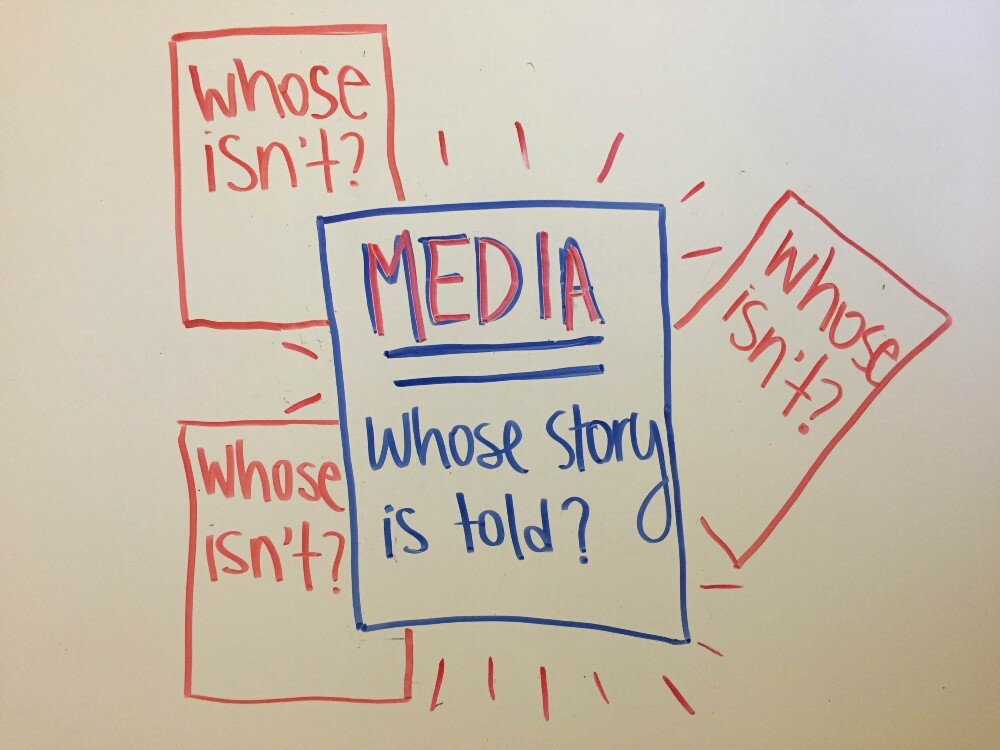

But if challenging conventional narratives and capturing nuance are core media values, why is it a reality that people sometimes feel their stories aren’t properly captured by mainstream media, if they are represented at all?

Confidence in media is at an all-time low, and sharing stories with the media can be triggering and re-victimizing for survivors of any trauma. Missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls face extremely biased coverage by Canadian media. People with marginalized identities (including people of colour and LGBTQ+ people), especially those who face marginalization on multiple grounds (such as transgender women of colour), say that sometimes they are led to believe their stories are too complicated for news media. When these people do share sensitive and personal stories, they sometimes feel misrepresented or stereotyped.

We want to make sure that people have the access to information they need to understand and talk about issues that affect them. As a reporter at Discourse Media, I’m part of a team that’s thinking a lot about how we can try new strategies to more deeply listen and engage with communities.

For me this has meant shifting my attention toward learning, building relationships and reporting on issues around gender, sexuality and gender-based violence. On Sept. 29 and 30, I attended a conference called “The Power of Our Collective Voices: Changing the Conversation on Sexual Violence at Post-Secondary Institutions.” As I listened to survivors and experts talk about experiences with media, the following stood out:

'Who are we giving opportunities to tell stories?' @AnnaSoole on challenging the idea of a single narrative. Inspiring me re: #MediaCulture

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

Trans women of colour face more sexual violence-also hear from media their stories too complicated to be heard -@aelizabethclark #CCSV2016

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) October 1, 2016

such a powerful reminder. @EndViolenceBC #bcpoli #MMIW #highwayoftears pic.twitter.com/BAuuynOWlz

— Brenda Slomka (@brenda_slomka) September 30, 2016

The assumption of "the perfect survivor". The stories covered are usually heterosexual, white female narrative.

— Farrah Khan (@farrah_khan) October 1, 2016

At the conference, I listened to speakers and panels, and asked this question to experts and survivors:

How can media reflect the diversity, the difference and the nuance of stories about sexual violence while placing them in the context of larger systemic issues?

Here’s what I’m learning:

1. Stick around long enough to get details right and to see and represent the big picture.

Most newsroom reporters are increasingly expected to cover all subjects and produce content extremely quickly. Most of the time, reporters likely don’t have the luxury of spending hours researching a story in its context before producing a story.

At a place like Discourse Media, the news cycle doesn’t usually dictate our pace. This means we have an opportunity to spend time researching and developing relationships before we write stories. It’s essential for reporters to understand sexual violence in a way that allows us to avoid tropes and tell stories that reflect the existing diversity of experiences.

What are these tropes? One common mistake is the idea that people who experience sexual violence respond in specific ways, and that those who continue to have relationships with those who abuse them are either blameworthy or lying. We see these clichés in the justice system and we see them in media.

Allowing reporters to spend time on individual stories, and to spend prolonged time working in one beat, enables them to see that every story is different and that no person or relationship is the same. At the same time, time spent working in one space means the opportunity to see the bigger systemic issue too.

I listened to Olga Trujillo, author of The Sum of My Parts: A Survivor’s Story of Dissociative Identity Disorder, give an account of her own experience with sexual violence. By clearly and thoroughly describing what she was experiencing and thinking in correlation with how she appeared in photos at different points in her childhood, Trujillo invited her audience to view survivors as humans who experience sexual violence but are not defined by it. She also underscored that there is no “right” way for a survivor to respond to sexual violence — that all responses are valid.

When asked how media could do better reporting on sexual violence, Trujillo suggested a framework not too different from her own presentation model: take the time to capture the details (in appearances, in experiences, in conflicts, in cases). Don’t shy away from the messiness of reality.

Sometimes, media does get this right: T. Christian Miller and Ken Armstrong’s “An unbelievable story of rape,” co-published by ProPublica and The Marshall Project in 2015, told the story of a victim who was never believed until the man who raped her was convicted for a string of other offences. This story stands out for its captivating narrative, portrayed in vivid and shocking detail. It doesn’t blame the victim. Instead, in capturing the truth with such precision, it radically validates the survivor’s story.

2. Really listen: how do people identify situations and themselves? What words do they use?

Just as a human story is almost never black and white, the words we use to describe people and situations are never “one size fits all.” While sometimes media may be required to use certain words for legal reasons, it’s important to use the pronouns, titles and descriptors that people identify with and use to tell their own stories.

Here’s a good reference for media coverage of the transgender community. The Dart Centre, a project of the Columbia Journalism School, provides excellent resources for producing trauma-informed media. Femifesto’s guide Use the Right Words provides great tips for media reporting on sexual violence. Farrah Khan, Ryerson University’s sexual violence support and education coordinator and Femifesto team member, presented some key insights from the guide. Here are the essentials that I took away:

Interviewing survivors: connect w resources, check your assumptions, be empathetic, respect survivors' boundaries. @farrah_khan #CCSV2016

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

Qs to ask survivors in an interview: #CCSV2016 @femifesto pic.twitter.com/4k4OtfTvLv

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

Don't: overuse words like "alleged" or "claims." Do: use"said," "according to," or "reports." @farrah_khan @femifesto #CCSV2016

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

It's not a sex scandal, it's sexual violence. -@farrah_khan. Use the right words. #CCSV2016

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

The words we capitalize speaks to power dynamics, says @farrah_khan. #CBC now capitalizes 'Indigenous,' @globeandmail doesn't. #CCSV2016

— Emma Clayton Jones (@emma_cjones) September 30, 2016

What would you add? What do you disagree with? Who is doing great reporting on gender and sexual violence?

I would love to start a broader conversation. Leave a comment here or reach out to me via email: .