It's 2017 — but some rape survivors in B.C. are waiting two years for counselling

We're all talking about gender equality, Justin Trudeau and Christy Clark included. But women who support the province's most vulnerable say the anti-violence sector's lack of funding is 'torture.'

The government money for Brenda Wilson’s job ran out at the end of March. But Wilson never wonders if she should go to work in the morning. She just keeps showing up.

Wilson, who is Gitxsan, is the Highway of Tears initiative coordinator at Carrier Sekani Family Services in Prince George, B.C. She, alone, supports and advocates for the families of the more than 30 women who’ve gone missing or have been murdered in the communities along Highway 16, the two-lane route connecting Prince Rupert and Prince George.

“I try to provide [support] through the little pots of money that we get from grants, here and there. But it’s really hard to keep a program going when there’s no funds available,” she tells me.

Wilson’s activism has never been about the money. It all began in 1994 when her sister, Ramona, went missing from Smithers, a town of about 5,000 people at the centre of the Highway of Tears. After 10 agonizing months, the 16-year-old’s remains were found close to Smithers’ airport. Twenty-three years later, Ramona’s family still hasn’t found justice — her murder remains unsolved.

“All this stuff just stays because it’s so traumatic that it’s forever engrained in your mind,” Wilson says. “In your heart.”

She pushes for better services and infrastructure on the Highway of Tears, while also helping families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) start the process of sharing their experiences with Canada’s national inquiry into MMIWG.

Wilson is one of a network of women in communities across B.C. who’ve dedicated their lives to ending violence against people of all genders. Like Wilson, many describe being connected to this issue through their own personal trauma. Another commonality: although they desperately want to help B.C.’s most vulnerable people and their families, a lack of money is getting in the way.

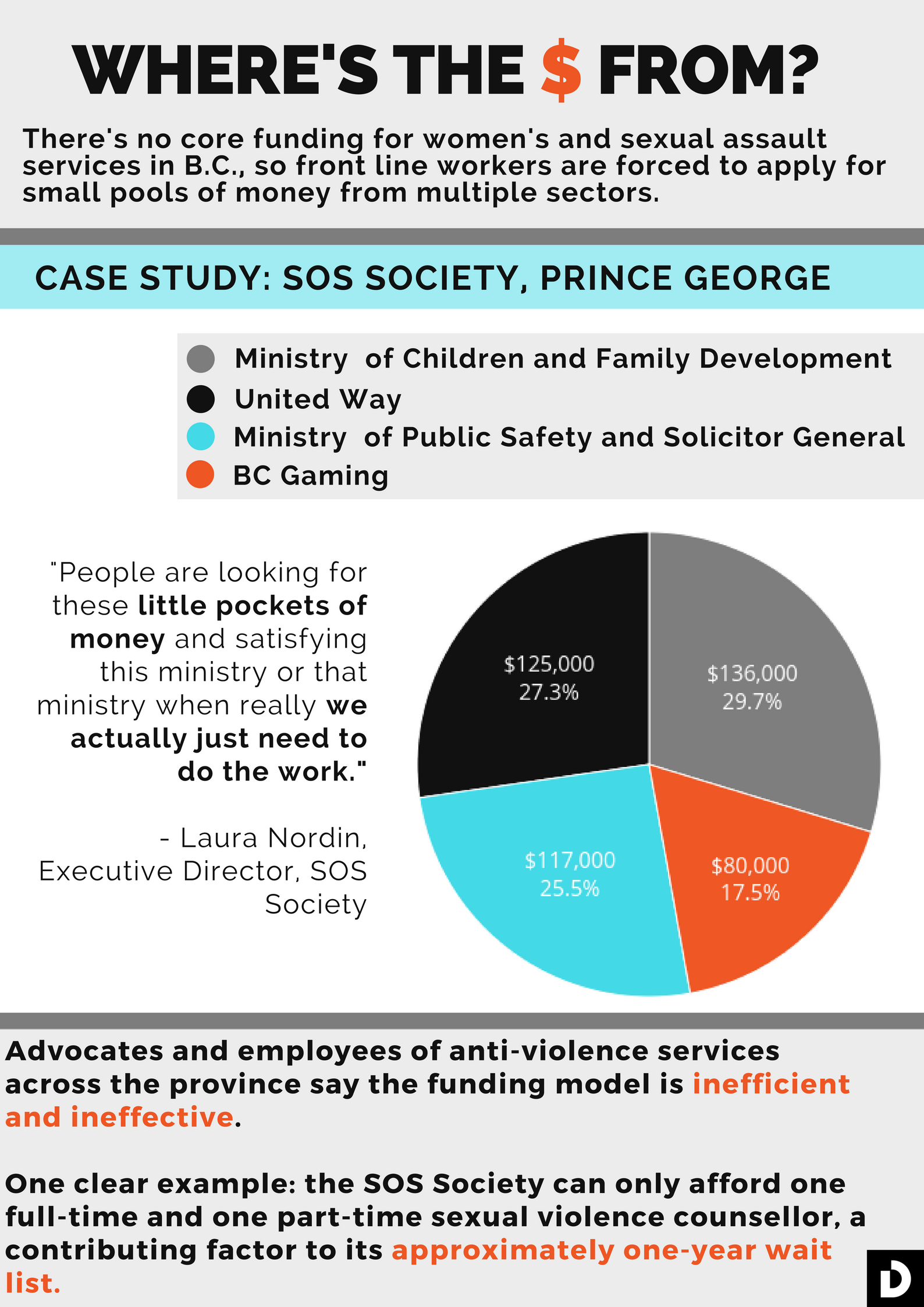

In 2001, provincial budget cuts removed core funding to programs addressing violence. Since then, community-based anti-violence groups have struggled to meet demand and stay open. They’re operating within increasingly complicated funding systems, patching together small pools of money from cross-sector government grants, social enterprises and private donations. Those working in the sector say they face severe understaffing and their employees are burning out.

This broken system creates harsh realities for people who’ve been assaulted, raped or are fleeing domestic violence. At some centres in B.C., people who seek help are told that they need to wait anywhere from two weeks to two years for one-to-one counselling.

Wilson only gets paid when small project funds come through from B.C.’s Civil Forfeiture office or the Justice Ministry. “Always struggling to find dollars for the Highway of Tears Initiative has been disheartening,” she says. “When the funding is there, the work is easier to do, and we are able to reach more people.”

![The province is really lagging behind in a number of areas [impacting women], compared to other provinces in Canada,- says Kendra Milne, Director of Law Reform, West Coast LEAF. Emma Jones](/discourse/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/emma1.jpg)

Kendra Milne, director of law reform at West Coast LEAF, believes the government funding system is failing some of B.C.’s most vulnerable women. Although B.C. finished 2016 as Canada’s strongest provincial economy, Milne feels the boom comes at the expense of “cuts and underfunding to social services,” and that “the result of that, of course, is that some people benefit from the economic security in the province and many, many others don’t.”

“We’re building what we imagine, or what we paint as economic success for the province, but it’s really coming at the cost of people, and it’s endangering their lives,” Milne adds. “It’s leading to people living in deep, deep poverty, it puts women at risk and it creates major barriers to them pursuing their own safety if they want to leave violent situations.”

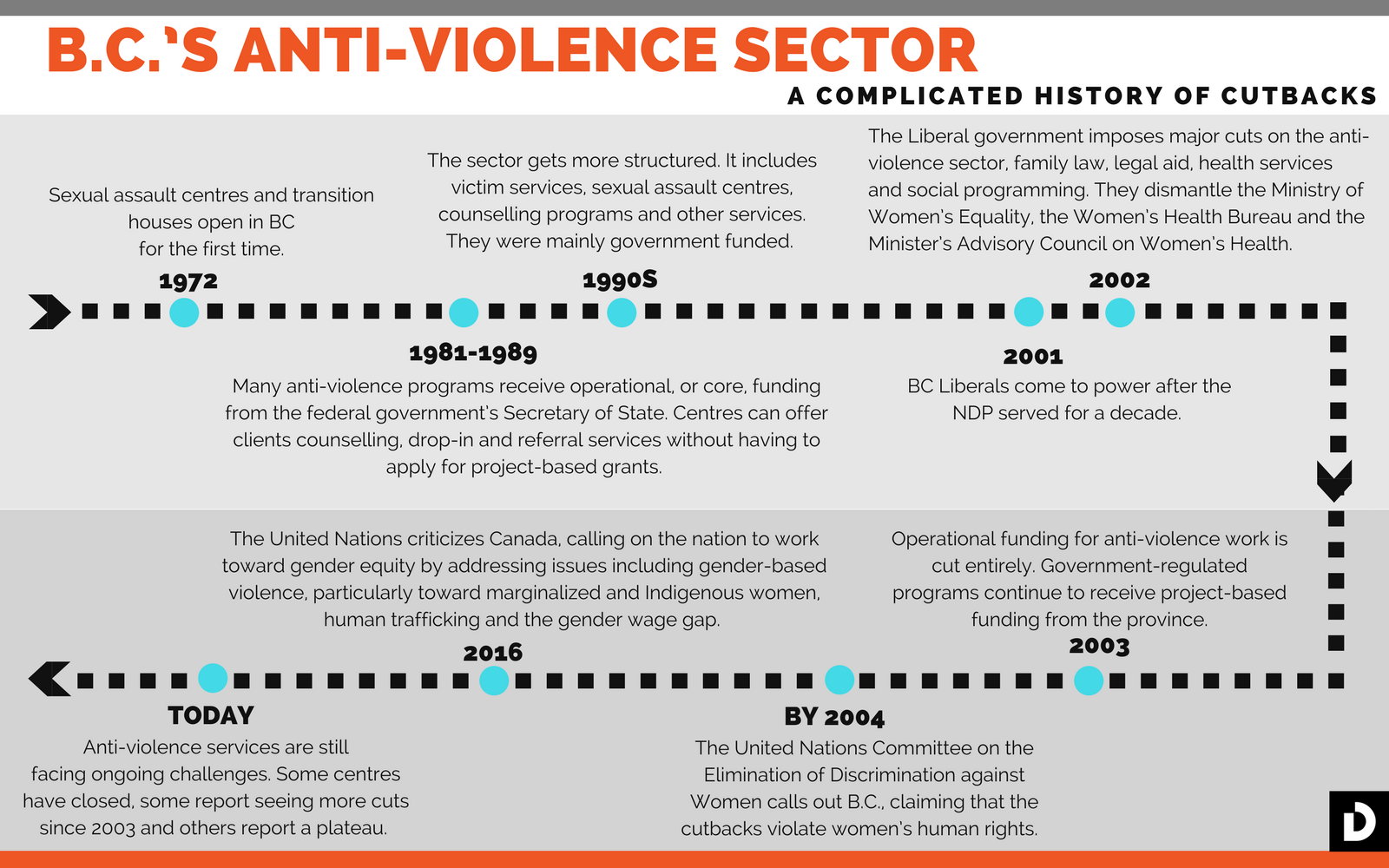

After a history of cutbacks, what’s left?

It’s not easy to understand how B.C.’s anti-violence sector works — partly because the province hasn’t had one central hub to monitor gender issues for more than 15 years. The Liberals came to power in 2001 after a decade of NDP leadership. A year later, they made major cuts to the anti-violence sector, family law, legal aid, and health and social programs. With these cuts came total chaos: the Women’s Equality Ministry, the Women’s Health Bureau and the Minister’s Advisory Council on Women’s Health — all gone.

It’s been a decades-long battle against B.C.’s “attack on women,” says Maureen Trotter, a member of the Quesnel Women’s Resource Centre (QWRC). Trotter has been with the drop-in, counselling and wellness centre through every bump and budget cut. The QWRC, which opened its doors in 1981, completely lost its core funding to the 2002 cutbacks

“We’ve been in mid-March, looking at the beginning of April, and nothing’s been confirmed,” she tells me. “Are we going to be able to keep the doors open next week?’”

Provincial cutbacks were so drastic that in 2003, the United Nations intervened. Its Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women specifically called out the province, saying B.C. failed to address its obligations to women under international human rights law.

Fast-forward to today, and not much has changed. The province’s latest budget, released in February, doesn’t mention new investments to women’s or anti-violence programs.

Without guaranteed funding, anti-violence workers like Trotter are forced to make impossible choices. Sometimes, it comes down to meeting with women or applying for grants and new projects. Organizations compete for funding from government departments, including the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, the Ministry of Children and Family Development, the Ministry of Justice, B.C. Housing and even B.C. Gaming, the provincial department responsible for gambling. Although some anti-violence programs receive annual funding, none are funded in a permanent way. The applications are never-ending and staying open is never guaranteed.

“As soon as you start putting women’s issues under health or social services, then you completely subsume the core issue,” Trotter says. “The Liberals cut so much.”

But is there a demand for more services? The Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General says the number of people in need of services is going down. It reports that from 2015 to 2016, around 34,000 people were referred to counselling and outreach programs after experiencing gender-based violence — an eight per cent decrease from 2013 referral rates.

Workers on the front lines don’t feel the demand for services easing up. The truth is, it’s hard to know for sure whether demand is decreasing. Gender-based violence is difficult to measure and, as women working for these services note, a decrease in referrals doesn’t mean a decrease in need. Fifty per cent of all Canadian women have experienced physical or sexual violence at least once after the age of 16. But of those abuses, a whopping 91 per cent never get reported to police. It’s unclear how many people who experience violence actually seek support like counselling.

‘The worst kind of political violence’

Women’s resource centres, sexual assault centres, transition houses and rape-crisis centres are only some of the available options to survivors of domestic and sexualized violence. To better understand the issues they are facing, I contacted more than 80 centres in B.C., and asked them about the programs they offer, how many employees they have to serve how many clients, the number of people on their waiting lists and where their funding comes from.

Only 13 centres responded. This group identified a slew of common issues: chronic underfunding, challenges paying rent, a low ratio of staff to survivors and a heavy reliance on volunteer services.

In Vancouver, the Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW) Rape Crisis Centre had one of the most drastic situations: inadequate funding for its services means women are waiting two years to begin their counselling process.

“I mean, it’s just mind-boggling when you think about the numbers,” says Irene Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer, WAVAW’s executive director. “We’ve never been able to address the service pressures, the amount of need that women have.”

According to WAVAW’s 2016 executive report, 240 survivors of sexualized violence were waiting for counselling at the centre, 39 per cent of them between the ages of 14 and 25.

“It feels like torture. It feels like the worst kind of political violence that you can enact,” Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer tells me. “There’s no recognition for the damage that the trauma of sexual assault does, and so that’s why it feels like torture.” Research shows leaving trauma untreated for extended periods of time can intensify survivors’ physical and psychological symptoms.

WAVAW has worked hard to fundraise and keep its doors open on a year-to-year basis, but at the end of the day, Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer feels they’re fighting societal and political apathy towards women who’ve experienced violence.

“There’s really a disinterest,” she says, adding women are expected to contribute politically and economically but are still denied basic services after experiencing trauma. “For women not to have essential services after they’ve been sexually assaulted is just mind-boggling.”

The Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General declined an interview to discuss the wait times for the anti-violence programs it supports. Instead, a representative wrote in an email: “Funding is allocated in a way to ensure residents in all regions of the province are able to access services.”

Survivors ‘deserve more’

Being home to a heavy concentration of B.C.’s missing and murdered Indigenous women is just one of many challenges Prince George faces. As the largest city in B.C.’s northern interior, women travel there from hours away, seeking services like counselling, detox and legal aid. It’s a commute that can be dangerous for those without car access.

“The biggest things for us in northern B.C. is education, prevention and service access,” says Dawn Hemingway, chair of the University of Northern British Columbia’s School of Social Work and member of the leadership team at Northern FIRE, UNBC's centre for research around northern women's health and experiences.

“The other issue,” she tells me, “is just whether or not people feel able to ask for help.”

Hemingway manages a network where women’s and anti-violence organizations across northern B.C. can share their research experiences, insights and events. This keeps her connected to women’s organizations province-wide. It’s tough to work in the anti-violence sector, Hemingway explains, citing the resilience of employees like Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer and Wilson. “Despite them being underpaid, and not provided the kinds of support they need as staff, they’re so committed,” she says.“ They do this work anyway.”

The Surpassing Our Survival (SOS) Society in Prince George is one centre doing everything it can to help people who’ve survived gender-based violence in the region.

“Somebody’s finally come through our doors — it’s taken them so much courage to come — and you have to say, ‘Sorry, you’re on a waitlist,’” says Laura Nordin, SOS Society’s executive director. Nordin was hired in June 2016, but the available funding only allows her to work two days a week.

“We try to figure it out and they figure it out, and you get through. But if you’ve been brave enough to come forward with something really hard — that you’ve been sexually abused — you deserve more,” she tells me.

“We try to figure it out and they figure it out, and you get through. But if you’ve been brave enough to come forward with something really hard — that you’ve been sexually abused — you deserve more,” she tells me.

SOS struggles to meet demand: its Stopping the Violence (STV) counselling program receives $117,000 annually from the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. The money funds one full-time and one part-time counsellor, but Nordin says SOS’ waitlist is about a year long. She believes one and a half counsellors is far from enough to meet community need for counselling.

And this lack of funding doesn’t just impact a survivor’s experience; Nordin says staff have been forced to scale back programs and can’t afford to attend yearly provincial training sessions.

“We’re just at a financial pinch point where it’s not really fair for somebody to go to training when we can’t pay our phone bill,” she explains. “You just have to make those hard calls.”

Solutions are ‘costly’ but in sight

Many see the systemic hardship of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada as a glaring sign that Canada has much work to do around gender-based violence. Last year, the UN criticized Canada, imploring the federal government to work towards gender equity by addressing issues such as human trafficking, the wage gap and gender-based violence — particularly towards marginalized and Indigenous women.

As the May 9 B.C. election approaches, Milne, West Coast LEAF’s director of law reform, says addressing these issues is partly a matter of “government putting their money where their mouth is.”

She adds, “I think we all agree that the disproportionate rates of violence that Indigenous women face are shocking and not acceptable. Because I think some of the solutions are costly, particularly looking at the root causes of violence, but it absolutely needs to be done.”

Although Milne’s hopeful the national inquiry into MMIWG will “create some political momentum,” she wants the government to go beyond creating plans and policies. She implores government to commit to social policy that supports and prevents violence against women in the first place, as well as empowers them to leave violent situations and begin to heal.

"We’re going to keep raising our voices to let them know that we’re here and we exist.” B.C. has acknowledged that gender-based violence is an urgent issue, an acknowledgement coming in the form of new and revamped policies and strategies. In February 2015, the province published a plan called “A Vision for a Violence-Free B.C.” This “roadmap” includes financial commitments to many programs and the promise of a new provincial sexual-violence policy. In June 2016 and February 2017, respectively, federal and provincial documents called attention to the issue, tabling plans to end gender-based violence.

Women working in the anti-violence sector have long said solutions aren’t elusive. In fact, many on the front lines feel they’ve been shouting solutions to deaf ears for decades. For Wilson, who works to support families of MMIWG, they start with giving her the resources to do her job.

“I think that the government needs to recognize northern British Columbia, and not to forget that we are a part of Canada,” she says. “They cannot leave us out any longer. We’re going to keep raising our voices to let them know that we’re here and we exist.”