Where are we now?

Possible Canadas

What do you want Canada to be? This is the question 10 student journalists posed to their campus communities. They interviewed hundreds of students on 10 campuses, then produced in-depth investigations into how Canada could start to realize these visions. What did they learn? That despite all the stereotypes of disengaged millennials, young people have a lot to say about the future of our country. Explore the 10-part series from the Possible Canadas fellowship about how we, as a country, can get to that future.

On Oct. 19, 2015, Canadian voters chose a dramatic change for their government. The long election campaign pushed issues like the economy, religious freedom and our crumbling infrastructure to the foreground. It also challenged Canadians to articulate how they saw this country and what they wanted for its future. An energized population voted in numbers that hadn’t been seen in decades. 69 per cent of eligible Canadians voted, the highest turnout since 1993. However, other than reduced tuition, there was little consideration given to what young people want for this country.

During his acceptance speech, newly-elected prime minister Justin Trudeau said that Canadians sent the message that “it’s time for change: a real change.” That’s all well and good, but what sort of change do we want? What are our priorities?

In an earlier article in this series, editor Tari Ajadi argued that Canada needs to shift discourse about our future and meaningfully listen to all Canadians, especially young people. But how do we know how to move forward if we don’t know where we are now?

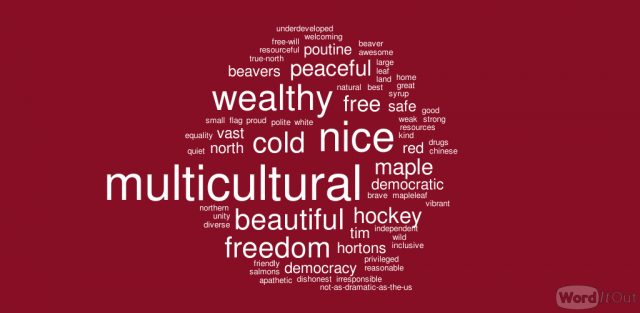

To better understand how young people understand Canada, I gathered students’ opinions at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in Burnaby, B.C. By asking students via GroundSource, a tool that allows journalists to ask questions via mobile phone, some common themes emerged:

Multicultural, wealthy and nice. And the experts seem to agree. These perceptions of Canada are common across many groups, young and old, rookie and professional, according to Dr. Rémi Léger and Dr. Laurent Dobuzinskis, two professors in SFU’s political science department. But is there any truth behind our stereotypes?

The troubled roots of Canadian multiculturalism

The vast majority of people I talked to about Canada said the nation is “multicultural,” or some variation of the term. Léger and Dobuzinskis said the same thing almost immediately when I spoke to them.

If you take public transit across Metro Vancouver, you’re probably going to hear a few languages other than English. Only 58 per cent of Vancouverites have English as their first language, according to the 2011 Statistics Canada census. This diversity isn’t exclusive to B.C.’s largest city — there are over 200 languages spoken in Canada, and about a fifth of our population is foreign-born.

According to Léger, how we discuss that diversity is also different from Europe or other parts of the world. “In Canada, when you meet someone new, within five minutes you’re asking, ‘Where was your family from?’” he said, adding that in other countries the same conversation can often be disconcerting or insulting. So what is behind our unique culture of proud multiculturalism?

Since far before Confederation, those origin stories have been part of our history. The first inhabitants of North and South America were migrating peoples crossing from Asia via the Bering land bridge. They spread across modern-day Canada, developing into hundreds of distinct cultures with dozens of distinct languages.

A powerful example of international cooperation during this period was when the Iroquois Confederacy formed, some time between 1570 and 1600 AD. Brought together by the Great Law of Peace, this confederation included five previously warring First Nations peoples in order to solve disputes diplomatically and increase their prosperity.

European cultures also coexisted in Canada before Confederation. French and English settlers landed on the eastern coasts of North America in the 16th century. These neighbours were by no means friendly, but for the almost 500 years since then, Canada has had to manage French and English cultures side by side.

After Great Britain had gained almost all of the territories in the Maritimes from the resolution of the Seven Years’ War, it established Quebec with the Quebec Act in 1774. This act allowed the free practice of the Catholic faith and some use of French civil law. Although this law increased the amount of power Great Britain had over Quebec, it was an early example of the recognition of distinct cultures being a part of Canada.

“Of course we’ve had our differences,” Dobuzinskis said, referring to the conflict between the French and British colonies. He added that the reason why Canada has handled diversity better than some other countries is that we were “exposed to having some degree of understanding or tolerance from our history.”

Dobuzinskis also gave a sober reminder of how Canada has failed to act inclusively in the past. “We shouldn’t paint everything too rosy. It’s mostly over the last 50 years [that] we’ve had a record we can be proud of,” he said.

The preeminent example of Canada’s complete failure to treat another culture with dignity is the Indian Act, introduced in 1876. The act gave the Department of Indian Affairs authority to control the lives of First Nations people across the country. It was amended almost continuously for 60 years, becoming more and more restrictive, and even going as far as banning First Nations from raising money to pursue land claims in 1927. The government also established residential schools, forcing Aboriginal children to abandon their traditional culture and language, amongst other horrors. The Government of Canada offered a formal apology in 2008 for the terrible abuses that the students were subjected to, but the damage still lingers.

The turning point in how this country handled other cultures can be attributed to Canada’s adoption of a policy of multiculturalism in 1971, the first country in the world to do so. The policy advocated for the “freedom of all members of Canadian society to preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage.” These ideas are also reflected in the Canadian Human Rights Act, given royal assent in 1977, and later the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, signed in 1982.

Despite Canada’s history of diplomacy and acceptance, our tolerance has recently become a concern to some. During the recent election campaign, Canadians argued on how to handle religious expression as well as immigration. However, the election provided an avenue for Canadians to discuss what they thought it meant to be Canadian. Several parliamentary candidates said that when someone becomes Canadian, it is part of their responsibility to adapt to Canadian culture. Many others disagreed, saying that there is inherent value in diversity — that different cultures coexisting peacefully leads to a more vibrant country. This mosaic of cultures within Canada also has an important role to play in an increasingly connected world, as Canadians that understand many cultures can better participate in international trade, education and diplomacy.

What does it mean to be wealthy?

We usually think of somebody with a big house, a nice car and the ability to buy what they want at the grocery store without being controlled by what’s on sale as wealthy. The average Canadian isn’t so affluent that they can spend without thinking, but when I asked around, students at SFU told me that they saw the nation as wealthy.

In general, most of us can afford to get by, and our economy proved that it could weather insecurity even when the rest of the world was in trouble.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)'s website is a useful resource to look at Canada in context with the rest of the “developed” world. The OECD is an organization made up of 34 countries that span five continents. These countries collect and share data on employment, health and many other areas of research in order to “improve the economic and social wellbeing of people around the world.”

The Great Recession tested Canadian stability when it dealt a blow to global economies in 2008. Unemployment rates across the world skyrocketed and financial markets are still struggling to recover. We felt the effects of the recession here in Canada, but not to the extent of our neighbours. Dobuzinskis said that, “compared to most of the OECD countries, we’ve been doing well until about six months ago.” Canada did experience an increase in unemployment during the recession, but it closely followed the OECD average, and decreased to below average in 2010. During the Globe and Mail debate during the election, former prime minister Stephen Harper asked the audience, “Where would you rather have been in all this global economic instability?”

However, Canada didn’t make it through unscathed — Canadians have started to carry more and more consumer debt. The average Canadian owes just over $21,000, not including mortgages, according to a TransUnion report published earlier this year. An article from The Economist points to low interest rates for this increase in borrowing. The silver lining of the TransUnion report is that it also found that we’re paying off this debt in a timely manner and the amount of overdue payments is decreasing.

So far, we’ve looked at a fairly safe definition for wealth: employment and ability to pay off debt. Wealth can, however, also mean financial freedom. How much can Canadians actually buy with what we’re paid?

The Numbeo Cost of Living Index looks at, among other things, how much purchasing power inhabitants have in a city with an average wage for that city. The higher the index, the more the average wage can buy in terms of goods and services like groceries and entertainment. This helps give an idea of how much financial freedom the inhabitants of those cities have. As of the mid-2015 edition of this index, Canadian cities are at about the middle of the road. Out of the 25 Canadian cities included in the rankings, their wages can afford on average 45 per cent more goods and services than people in New York. That means for the same portion of their wage, Vancouverites can go out for dinner and drinks three times whereas New Yorkers can only go out twice.

Are we really all that nice?

Canadians will relentlessly brag about how polite and humble we are. It’s almost as though we have a secret pact to never let a bump or jostle go without apology. In possibly the most Canadian music video ever released, astronaut Chris Hadfield and his brother Dave commented on a so-called Canadian golden rule: “You stay out of my face, and I’ll stay out of yours.” Dobuzinskis offered that this is reflected in our diplomatic tone, saying that “we pride ourselves on our capacity to exercise soft power and moral persuasion” rather than military intervention.

Léger used the word “docile” to describe Canada, meaning something similar: “We won’t intervene in another country without the support of the UN, NATO or other countries,” he said. “We rely on international organizations.” Polite and prone to solving problems by discussion, Canada has translated this attitude into its infrastructure, making this a very “nice” place to live.

The Economist ranked Vancouver, Toronto and Calgary as very desirable places to live when it considered safety, healthcare, infrastructure and dozens of other factors. These Canadian cities placed as third, fourth and fifth most desirable in the world respectively. Crime has also been on the decline in Canada since 1990. Not only is Canada a desirable place to live, it’s also accommodating to visitors. After looking at factors like travel infrastructure, safety and natural and cultural resources, Canada was ranked eighth in the world on the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index. Other top contenders were European countries like Switzerland and Germany. National image has certainly helped spur Canadian tourism, as a survey done by the Reputation Institute this year found that Canada is the world’s most respected country.

Last, but certainly not least, Canadians have a high quality of life. The OECD Better Life Index ranked Canada as above average in a combination of factors like quality of housing, disposable income and personal safety.

While Canada is not perfect, we have a lot to be proud of

After all the negativity thrown around during the election, it’s nice to hear something positive about this country for a change. While the Great White North isn’t perfect, we certainly have a few things to be proud of — we are ethnically diverse, financially stable, safe and welcoming.

But where do we go from here? Politicians told us their different visions for Canada during the election, and while they disagreed on the details, nobody was arguing to keep Canada just the way it is. Our votes on Oct. 19 decided who would be in power to carve out the next step in Canadian history, and that decision might turn this country into something very different or keep it very familiar.

Already there are plenty of challenges for the prime minister-designate to respond to: a humanitarian crisis in the Middle East, the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference and the ratification of the Trans Pacific Partnership, for starters.

Possible Canadas aims to explore that next step, a big “what if” experiment applied to our whole country.

Keep reading to see what other young people across Western Canada have to say, and in time, we may see some of those possible Canadas come true.

Possible Canadas is a partnership of diverse organizations that share the goal of supporting forward-looking conversations about the future of Canada. The project is produced by Discourse Media and Reos Partners, in collaboration with RECODE and the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. Partners’ support does not imply endorsement of the views represented.