How can we make bachelor’s degrees worth it for students?

The value proposition of a university degree is plunging. How can students adapt in an uncertain economic future?

Possible Canadas

What do you want Canada to be? This is the question 10 student journalists posed to their campus communities. They interviewed hundreds of students on 10 campuses, then produced in-depth investigations into how Canada could start to realize these visions. What did they learn? That despite all the stereotypes of disengaged millennials, young people have a lot to say about the future of our country. Explore the 10-part series from the Possible Canadas fellowship about how we, as a country, can get to that future.

Denis Luchyshyn graduated from the University of Victoria in 2014 with high hopes and confidence in his newly-obtained business degree. “We had a lot of emphasis on hands-on work experience. We had co-op programs that I was a part of,” says Luchyshyn. “I did three semesters of work, so in terms of my education I felt a lot more prepared than my friends.”

Even after being readied for the workforce, Luchyshyn saw his hopes dashed after a few months in the real world. He had started a job straight after graduation but, while the pay was decent and there were prospects for growth, he just couldn’t see himself making a career of it. “I was selling online ads. We all know how much people love that.”

He and his friend Clinton Nellist noticed that a lot of their hard-working and educated friends were in a similar situation: either they couldn’t find a job in their field, or they couldn’t find work at all. That's what sparked the idea of Road to Employment, a documentary film project created by Nellist and Luchyshyn to address the issue of unemployment amongst young Canadians. The two travelled across the country, talking with students, graduates and employers to get an idea of what the situation looked like on a national scale and find the solution to student employment woes.

Across the country, they found many students worried about their prospects after university. And those who have left the relative comfort of school are having a hard time finding entry into a career they are passionate about.

It’s a story we hear over and over again. But does this mean that Canada is experiencing a decline in meaningful and interesting jobs? Not necessarily. Rather, on their cross-country tour, Luchyshyn and Nellist discovered a key gap in the education system that, if filled, might hold the key not just to a more meaningful future for Canada’s youth, but also to the future of the country’s economic success.

The value proposition

A university degree has always seemed like the golden ticket to a wealthier life, and the numbers up until now back it up. According to a Statistics Canada study that looked at the earning differential between those with post-secondary education and those without from 1991 to 2010, “men who had obtained a bachelor’s degree by 1991 had earned, on average, $732,000 more than those whose education ended at a high school diploma. For women, the difference between the two groups was $448,000.”

That changed in the mid-2000s when Canada experienced a brief period of the wage gap closing slightly between those with post-secondary education and those without. It seemed at the time as though the golden ticket had lost some value. Andrew Parkin, an independent public policy analyst and a research fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute, says this was not the case.

"It didn’t mean there was a lower value of postsecondary education," he explains. "Instead, a resource and construction boom increased the earnings of those working jobs with lower levels of education." That wage gap opened back up once Canada entered a recession in 2008. “The recession reversed the situation. Those without a postsecondary education were much harder hit,” says Parkin.

But just because employed people with jobs are earning more money than their less formally educated peers doesn’t necessarily mean that it isn’t getting harder for new grads to turn their golden ticket into a pot of gold.

While employment rates in Canada have, by nearly all accounts, actually increased over the past decades, the employment rate for graduates with bachelor’s degrees has been dropping. Employment statistics in Canada are much better now than they were 20 years ago. In 2012, for example, 61.8 per cent of working-age Canadians were employed, as opposed to 58.7 per cent in 1995. The unemployment rate has gone down from 9.5 per cent in 1995 to 6.8 per cent in 2014. Youth unemployment has gone down too, from 16.1 per cent to 13.5 per cent in the same time period. The outlier in these trends is labour force participation, or the amount of working-age Canadians who are either employed, or unemployed and looking for work. Right now, participation is at the lowest rate since the year 2000, mainly because the baby boom generation is moving towards retirement. Read more about that here. According to Statistics Canada, in 1990 79.1 per cent of 15- to 24-year-olds that held bachelor’s degrees were employed; that number is now 71.9 per cent. That’s saying a lot, considering that the percentage of bachelor’s degree holders in the working age population increased four per cent from 2000 to 2010.

That means that students like Myles Regnier, a Langara College student in his second year of arts and environmental studies, are in an increasingly competitive market.

“A lot of jobs will need a degree, but the specificity of it doesn’t necessarily matter,” Regnier says. He believes that leads to many graduates of different disciplines vying for the same positions. Regnier plans to pursue a master’s degree after his undergrad in hopes of having a more competitive edge. But even if he does, statistics are still not drastically more in his favour. A 2010 Statistics Canada report on post-secondary graduates revealed that the rate of full-time employment for those with master’s degrees is only two per cent higher than for those with a bachelor’s degree.

So why is a degree losing its clout in the job market?

"The world is changing, and fast"

Based on what Nellist and Luchyshyn found when talking to employers across the country, they believe that there is a deep disconnect between what industries today need and what university grads are providing.

“The world is changing, and fast. Technology, communication and the way we live, travel and do business are continuously evolving. In the relationship of school and industry, industry is typically the leader and innovator because it’s sink or swim,” Luchyshyn says. The result, he says, is that while industry is steaming ahead and changing with the times, universities are slow-moving behemoths that are struggling to help their students understand what employers today need, let alone give them the training to provide it.

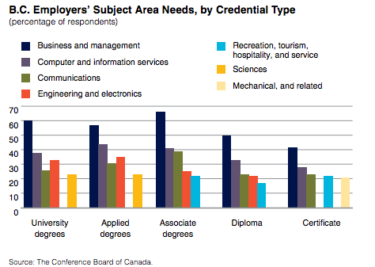

And this isn’t just a problem for the grads. A 2015 report produced by the Conference Board of Canada found that the province of British Columbia, for example, is missing out on as much as $4.7 billion in economic activity and over $600 million in provincial tax revenues annually due to too few people having the proper education for the jobs required. According to the report, the five most prevalent subject areas where university graduates are needed is, in order: business and management, computer and information services, engineering and electronics, communications, and sciences.

Some say the onus is on students to pick up the slack and revive the value proposition of a university degree.

“I’m more inclined to see higher education being used as a form of development for students in terms of a holistic understanding, rather than a specific way of funnelling them into jobs,” says Don Krug, a professor in the faculty of education at the University of British Columbia. “It’s a disservice for the students when you end up creating these pathways that lead into particular positions, but then also limit the student’s ability to understand the bigger picture.”

Krug notes that higher education’s current structure is part of what could limit graduates from becoming truly innovative in their field. He says that “disciplines, by their very nature, are separated from other disciplines, so what you end up having is students have a very difficult time in trying to make connections across these types of disciplines.”

This focus on one discipline means that students might miss out on subjects or skills that they might be really good at.

Sean Aiken, the creator and subject of the One Week Job project, knows a thing or two about working in places he may not have wanted to work. Aiken spent the year after his graduation travelling across the United States, working one job per week for all 52 weeks of the year.

“Many people are coming out of college thinking, ‘I don’t know what I want to do with my life,’ and they end up with a degree and then they end up doing nothing,” Aiken said in an interview with CBC’s Mark Kelley. “I think the biggest important thing is that they get active and go do something … as soon as you step into the workplace you start learning the things that you like to do, the things that you’re good at and the types of situations you’re going to be most successful in.”

But students shouldn’t have to do that alone.

During the cross-country trip, Luchyshyn found several programs that expose young people to different career options even before they hit college or university.

Career Trek is a program operating in Manitoba that takes elementary school kids to visit different post-secondary institutions. The idea, Luchyshyn says, is to “expose them to a variety of different careers and different professions, and just get them in touch with that environment, so they start thinking about their future and why school is important.”

Another innovation that Luchyshyn noted is Youth Fusion, a Montreal-based program that gives high school students hands-on experience in robotic engineering, entrepreneurship, journalism and other professions.

But for those who have already made the long awkward journey through elementary and secondary school, Luchyshyn says that co-op programs, while quite standard, are not offered in all faculties. Rather, they are mostly focused on business and engineering students.

The University of Waterloo, he says, has one of the only major co-op programs in the country. It is offered as part of more than 120 of the university’s undergraduate programs.

No silver bullet

When asked if he had found the answer he was looking for, Luchyshyn says the reality is that “there’s not a silver bullet.”

“It requires the parents to really break down some facts for people our age, and for people in high school, to understand the reality of the job market,” he says. “It requires employers to step up and create opportunities for young people to go in and get hands-on work experience that is more than just serving and fetching coffee. It requires the government to create incentives for employers to make those programs available.”

Newly-elected prime minister Justin Trudeau’s platform offers some hope.

Trudeau promised that he “will invest $40 million each year to help employers create more co-op placements for students in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and business programs.” That wouldn’t just mean that students get more work experience for their resume. It would mean that they would better understand what they even need to be learning in university in order to fill those jobs permanently once they graduate. And the incentive will be there for employers to make that happen if Trudeau holds to his additional promise to waive employment insurance premiums for companies that hire people between the ages of 18 and 24 in permanent positions.

The Liberal party platform also promised to make it easier for students to pay off their loans (the average student debt owed by bachelor’s degree holders in Canada is $26,300) by ensuring that “no graduate with student loans will be required to make any repayment until they are earning an income of at least $25,000 per year.”

But government policy aside, says Luchyshyn, the bottom line is to use the time you have in post-secondary wisely to network and connect with people who could potentially help you find a career down the road. “That time is really crucial to get hands on and be able to find a direction,” he says, true to his business school roots. “Make the right connections so that when you do leave, you’re already on the right track.”

Possible Canadas is a partnership of diverse organizations that share the goal of supporting forward-looking conversations about the future of Canada. The project is produced by Discourse Media and Reos Partners, in collaboration with RECODE and the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation. Partners’ support does not imply endorsement of the views represented.