B.C. families in limbo due to severe court delays

Provincial Court data shows child protection cases are the most delayed in British Columbia. We visit Williams Lake, a town with some of the longest wait times, to find out why.

| Not enough judges | Courts are overbooked | 'I’m getting my kids back' | Finding a lawyer | Social workers short staffed | Parenting programs | Punishing the poor | Different standards for criminal cases |

Child protection social workers are trained to remove children from their homes and their families as a last resort. But it happens.

Most of us can’t imagine what that separation feels like for the child, the parent, the siblings, the grandparents and the social worker. And this is only the start of the process — one that can take months or even years to resolve.

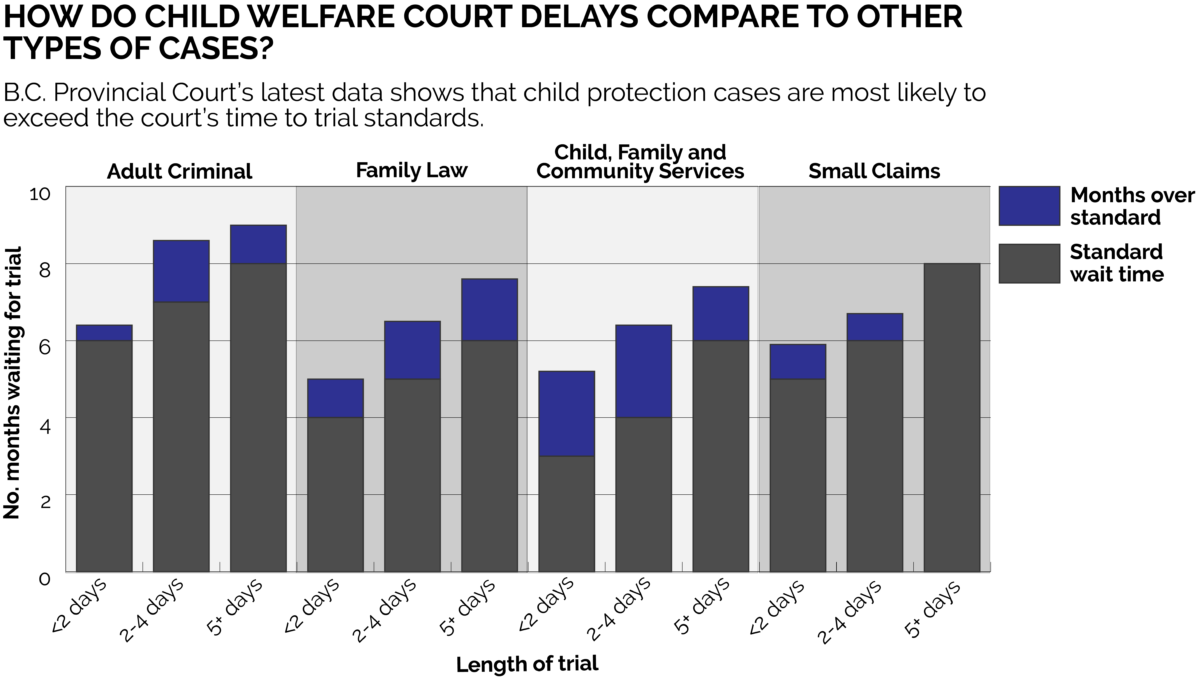

In B.C., child protection cases have the longest delays — more so than criminal, family and small claims cases. Discourse Media has reviewed the latest data from the B.C. Provincial Court and found that families are waiting months longer than they should, according to provincial standards, for their trial to get started. Never mind all the adjournments that tend to follow.

The court’s data also tells us that certain communities are affected more than others. Williams Lake, B.C., is one of those places. Here, families are waiting about nine months for their hearing to start. That’s up to six months longer than families should be waiting according to the court’s standards. Meanwhile, their kids are in care — possibly across town, possibly in a different community altogether.

Peel back the curtain on these delays and you’ll find a system overwhelmed: courtrooms overbooked and understaffed, social workers scrambling, and parents and kids — waiting.

Not enough judges

“We need resources,” says local lawyer Clare Hauser. Since being called to the bar in May 2016, Hauser says she’s worked mostly on child protection cases.

She’s among a group of lawyers who tell me that the Williams Lake courthouse used to have more judges. There’s currently one full-time judge and a part-time senior judge sitting in Williams Lake. A staff member at the court registry confirmed that the court is currently down a judge. Fewer judges means less court time. It means families tangled up in child protection cases are waiting longer for answers.

"Honestly we need more judges and court time and court staff and sheriffs,” says Hauser. It’s hardly the first time people have called for more judges in this province.

Back in 2005, the B.C. Provincial Court had the equivalent of 143.65 full-time judges. By 2010, that number had dropped to 126.30 and the court was “strongly recommending” that the number of judges “be restored to the 2005 level.” That didn’t happen. As of September 30, 2017, the court had 127.20 judges.

Carol Baird Ellan sat as the Provincial Court’s chief judge from 2000 to 2005. This is before the number of judges plummeted. Still, she remembers wrestling with delays and adjournments. She says she was “horrified by the timelines” in child protection cases.

“You’re beating your head against the wall trying to get it solved,” she says.

It was under Ellan’s leadership in 2005 that the Provincial Court created “time to trial” standards. The idea was to clarify how much time should be allowed to elapse — at a maximum — between the day that a case is ready to be heard and the day that the trial is scheduled to begin. In setting these standards, the court gave certain kinds of trials more priority than others.

“Child protection’s right up at the top,” Ellan says. “Partly because of the guidelines in the legislation, which creates an urgency” — for obvious reasons. You want to establish a sense of permanency for children in care as soon as possible, whether they’re going home to their families or not.

Every six months, Time to Trial Reports give us a sense for how quickly the court is administering justice. We can see when a specific kind of trial in a specific region might begin, based on the court’s assessment of the region’s caseload and resources. The last two reports show child protection trials are the most delayed.

Courts are overbooked

One way the court in Williams Lake tries to ensure that child protection cases get a fair share of judges’ time is by dedicating a specific week every month to hear these cases. It’s a common strategy in courtrooms across the province — but there’s a catch. Courts schedule these weeks like flights: they overbook them.

Several child protection trials will be scheduled for the same time, the idea is that some parents will come to an agreement with the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) out of court in the interim.

The upside of this strategy, says local lawyer Julian Tryczynski, is that “something is going to get heard because [the court is] frickin’ overbooked. The court’s time is going to get used up.” The downside, he says, is that during these weeks more people may show up than the court has resources to hear. And some people will have made considerable investments to get there.

Maybe they hitchhiked from a remote community, booked time off from their minimum-wage job or flew up from Vancouver. And then “someone gets bumped, and they go six months down the road,” Tryczynski says.

These “bumps” can be really hard on families, says Carol Archie. She works closely with families who belong to the T’éxel’c community, one of 17 bands in the Secwepemc Nation. As the community’s senior social development manager, she often goes with parents to court.

“Each time a parent goes in [to court] they’re thinking, ‘Okay, I’m going to be one step closer to getting my kids back.’ And then they walk in and within five minutes, oh, it’s adjourned until next month. And it’s devastation after devastation from a parent’s point of view,” she says.

“You not only have your own devastation, but you’re carrying the devastation your children have. That’s huge guilt,” says Archie.

In B.C., there’s been a rise in new child protection cases. According to the Provincial Court’s latest annual report, for the 2015/16 fiscal year, these cases have increased every year since 2011, for a cumulative increase of 22 per cent.

This spike in caseload adds complexity to an already highly complex problem. More cases demand more court time, more judges, more sheriffs — more of all the things insiders say the court is already short on.

'I’m getting my kids back'

James and Brenda had six children together. When the couple — whose names have been changed to protect their children’s identity — split up, two of the children went to live with James and four went with Brenda. The latter four quickly wound up in foster care, and spent the next few years bouncing between temporary placements in the Williams Lake area.

In early 2016, James was in prison for a four-month stretch when he learned social workers wanted to place the four kids who had been in foster care into permanent care — in other words, take away his parenting rights. Social workers intended to return the children to their mother, but she wasn’t in a position to take them. They felt it would be in the children’s best interest if the government became their permanent guardians. James felt differently.

The 35-year-old also grew up in foster care, and while he was in prison last year, he says he spent long hours reflecting on his childhood. He came to a decision: “I’m getting my shit together. I’m getting my kids back. They are going to come home, no matter what anybody says.”

He got out of prison and picked up his two children from his sister’s place, where they’d been staying while he was in jail. He then told the social workers that he wanted to take his other four children out of care and bring them home. The social workers felt this was a bad idea. James didn’t understand.

“Me and my kids had a roof over our head. I was bringing them to school every day. I was picking them up from school. I wasn’t drinking. So, what were the concerns? They wouldn’t tell me,” says James.

The case went to court. And James spent the next year fighting to bring all his kids together under one roof.

Finding a lawyer

James’s trial was first postponed to give him time to apply for legal aid. Parents whose children are removed are legally entitled to representation. In B.C., this is provided by the Legal Services Society which handles 2,500 child protection cases a year.

James found the application process “fairly easy,” but cumbersome. “They couldn’t get things set up for me right away, as quick as I was wanting to,” he says. It was stressful not knowing who his lawyer would be.

!["Williams Lake had 225 new CFCSA [child protection] cases (including subsequent applications) in 2016/17," according to an email from the B.C. Provincial Court. Brielle Morgan](/discourse/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/20170920_100937-1.jpg)

“Whether you’re going to get a lawyer that’s going to fight for you, whether you’re going to get a lawyer that’s just going to toss it aside — you just never know,” says James.

But even if you’re happy with your lawyer, you might not get to keep them. These “legal advocates are severely constrained by limited legal aid hours,” wrote Grand Chief Ed John in his 2016 report, Indigenous Resilience, Connectedness and Reunification — From Root Causes to Root Solutions. Sometimes their hours run out before a trial is over, and so parents have to reapply for legal aid. And this takes time.

“Every time you switch a lawyer, they have to use up their limited time to read the disclosure package,” says Sam, who works on contract as a lawyer for the MCFD in northern B.C. Because Sam didn’t have permission from their superiors to speak with me, they asked to remain anonymous, and so I've used a pseudonym.

“There’s one file I have that has 10 binders of disclosure,” says Sam.

The MCFD says it’s working closely with families to solve more problems out of court and reduce adjournments. “One way we’re doing that is through more family conferences, and meetings where a neutral third party facilitates the development of family plans and/or reaching consent on court orders,” wrote a ministry spokesperson via email.

Social workers’ lack of resources trickles down

James’s trial was adjourned again when his old social worker was replaced. His new social worker, Kristy Joseph, “needed time to get familiar with the file,” he says. And she wanted more time to “do the checks and everything.”

Social workers do “checks” on parents to make sure they’re doing the work they’ve agreed to do.

“Offices that I’ve worked in, not just this one, they’re all short-staffed"

Are they showing up for all their supervised visits and their counselling sessions? Did they complete the parenting program? Are they taking their weekly “piss tests” (as James calls them)? Sometimes the social worker needs more time to confirm that the parent has done the work. And so they’ll ask the judge for another temporary custody order extending the case for up to three months to as long as a year.

As of September 2017, Joseph says she was the only fully-delegated child protection social worker at Knucwentwecw Society, a Delegated Aboriginal Agency (DAA) which provides services to Indigenous communities on behalf of the MCFD. They support children and families in four band communities close to Williams Lake. Just recently, two more social workers at the agency became fully delegated, which means they have the authority to remove children if they deem it necessary. Their delegation is great news for Joseph, as it takes some of the work off of her overstacked plate.

“Offices that I’ve worked in, not just this one, they’re all short-staffed, so that puts delays on checking in on supports and services that parents have accessed,” Joseph says. This can be extremely frustrating for parents.

“Rather than them being in care, I wanted my kids home,” says James. “The sooner the better … I had everything they needed. I had beds, dressers, clothes, food — stocked up and everything.”

A report released in March by the office of the Representative for Children and Youth (RCY) found that social workers at B.C.’s 23 DAAs — which “serve nearly 1,900 of the approximately 4,400 Indigenous children in the care of the B.C. government” — are getting slammed across the board. Workers interviewed by the RCY said they were carrying “an average of 30 cases at a time — 50 per cent more than is recommended by the Aboriginal Operational and Practice Standards and Indicators (AOPSI) guidelines.”

The MCFD says it is working to bridge the gaps to better support vulnerable families and social workers. In an email, a ministry spokesperson listed several measures it's taking, including this one: “September’s Budget update recommits $14.4 million to help ensure that DAAs are funded at levels equitable to the ministry, and provides a further $24.2 million for family supports, culturally appropriate services and to place additional staff — both from DAAs and MCFD — within Indigenous communities."

Get with the program

Lynn Dunford watched James do “nine different parenting programs” while his case moved through the court. “That was a tough one,” she says of his case. “Because there were times when he was expecting to go to court and they kept delaying, delaying, delaying.”

As manager of the mental health and addictions program at Three Corners Health Services Society in Williams Lake, Dunford helped James connect with the programs and resources he needed. She says it took him a while to warm up to the idea of going to a parenting program.

“I guess it had something to do with being scared of having to be a father to six kids on my own,” James explained. “It’s a big change going from working all the time to having two kids — wasn’t so bad — and then thinking about all six. That was a scary thought, right?”

But he knew he had to do the work. “There was certain guidelines that were laid out for me to accomplish in order to get my kids back. I accomplished everything they’d asked [of me],” he says, thumping the table.

“[I] was handing in certificate after certificate to the ministry … anger management, respectful relationships … aboriginal parenting,” he says. “They told me I didn’t need to do anymore, and I told them I wasn’t doing it for them, that I was doing it for myself.”

While James didn’t have difficulty accessing programs, some parents get stuck on waitlists. Carol Archie has seen parents get waitlisted for “anywhere from three to six months” for trauma programs or alcohol and drug treatment. They need to finish these programs in order to get their kids back, and so their case gets adjourned.

In the 2014 report, Choose Children, social workers in the Williams Lake area reported “strong concerns over unmanageable waitlists for all services.”

“There’s that discouraging factor,” says Archie. “It’s like, adjourned again? Really? Now I have to wait until next month, and that’s another month away from my kids.”

Punishing the poor

While James chose to make the best of a bad situation by accessing so many resources, he had at least one advantage: he lived in town.

For people who live far from cities and towns where support services are concentrated, meeting the requirements to get their kids back can be a huge challenge — especially if they don’t have much money. In his 2016 report on Indigenous child welfare in B.C., Grand Chief Ed John wrote, “Parents whose children are being removed generally have few to no financial resources.”

And yet they’re being asked to take time off work so they can get to supervised visits and counselling appointments and parenting programs and court appearances, which might be a half day’s journey away from their community.

Dora Demers works for Xatśūll First Nation. Their community is only a 15-minute drive up the highway from Williams Lake, but even that short distance makes a difference for people without bus fare.

“If [I’m] asked to go to a parenting workshop and I don’t have a ride to get there, nobody’s going to provide me a ride there. Nobody’s going to give me gas money,” says Demers, the band administrator. “I’ve seen people hitchhiking to go to their parenting workshop. And they don’t make it? Sorry, you can’t have visitation next week.”

Former Chief Judge Carol Baird Ellan remembers fighting a proposal to close the Squamish courthouse in 2002. A pre-closure assessment found that “Squamish has a sizeable aboriginal community which is over represented in the criminal justice system, as well in CFCSA [or child protection] matters. Many, many litigants and accused do not drive.”

When the courthouse closed, Ellan saw the impact on parents who had to get to North Vancouver for their trial. “There’s no bus that goes there except the overnight Greyhound from Whistler … [It was] just inaccessible.”

Gina Mortensen, Xatśūll First Nation’s designated advocate for children and families, often goes with parents to court. She says that, beyond transportation issues, cases can be delayed because it’s difficult for chronically poor families to meet the court or social worker’s expectations.

“Oh, great, you accomplished housing! Good for you. That’s awesome. But it’s not good enough. You should have two bedrooms because you’ve got a boy and a girl … Pretty soon, it’s three to six months and the kids aren’t in the parents’ care yet because of the bedroom,” she says. “Because of housing.”

In its guidebook Parents’ Rights, Kids’ Rights, the Legal Services Society suggests actions parents can take to ensure they’re on the same page with their social worker. LSS advises parents to “ask the child protection worker to say exactly what you have to do and what will happen if you don’t meet all the terms.” Parents should have a written agreement that is “clear about how the child protection worker will decide when you have done something — and if you have done it well enough.” This is important, LSS says, because if you don’t complete all the terms of the agreement, “there could be serious consequences.”

In a voice tight with frustration, Mortensen recalled a mediation session in which she felt the social workers weren’t playing fair. “I just kept seeing this mom defeated,” she says. “You’re not supposed to be creating roadblocks … putting condition after condition after condition. That’s like playing cards and making the rules up as you go.”

A family lawyer in Vancouver put it to me this way: We’re disempowering parents at the time in their lives when they most need to be empowered.

“[Parents] say, ‘Hey, I’ve had it,’” says Dora Demers. “‘I’m not going to do this anymore. It’s like I’m never ever going to accomplish getting my children back.’ They fall. They go back to drinking. They go back to drugging. And everybody points at that person: ‘Well, I guess you didn’t want your kids back bad enough.’”

Different standards for criminal cases

In February of this year, James got some big news. The social workers were completely withdrawing their application for permanent custody of his children.

“The family had done everything above and beyond and worked extremely hard to get their children back,” says Kristy Joseph, the social worker who took over his file last fall. She says it’s “very rare” for social workers to totally withdraw an application for full custody and return children to their parents with no strings attached. No conditions. Case closed.

James is proud of the work he did to reunite his family, but he believes his children should have been returned sooner. Joseph, his social worker, agrees. “I think it’s possible that that [case] could have been agreed upon earlier,” she says.

B.C. doesn’t track how long child protection cases take. Discourse Media asked the B.C. Provincial Court for data and a spokesperson wrote in an email, “the actual average length of a child protection case (i.e., from first appearance to last court order) is not data that is currently collected by the court.”

“There is a systemic complacency”

If a family feels their case is taking too long, there’s not much they can do about it. Members of the public “have no means of compelling their case to proceed in a timely way,” says the court’s Justice Delayed report. “They also have no recourse if the court fails to do so.”

It’s a different story for criminal cases. In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada case R v. Jordan called attention to “the culture of complacency towards delay that has pervaded the criminal justice system in recent years”. The SCC took action, establishing deadlines for criminal trials in provincial and superior courts.

“They’ve made it so that your Charter rights are being infringed upon if you don’t get heard within a certain amount of time when you’re in custody,” explains lawyer Clare Hauser.

But there’s a flipside to this focus on quashing criminal trial delays. According to a 2016 report on B.C.’s justice system, “the priority given to addressing criminal cases in the Provincial Court can have negative effects on the court’s other responsibilities such as child apprehension, family law, and small claims.”

What does this mean for families caught up in child protection cases? Carol Baird Ellan described a typical scenario. “You’ve got two competing priorities at the top of the list for short-term trial dates. One is in-custody accused who’s got his rights at stake, and the other is the child who’s been apprehended and who needs her fate determined.”

“They’re fighting over the same priority or trial time,” she says. “The child protection [case] may receive less pressure to set an earlier date if they’re competing with an in-custody accused for that time.”

In B.C., there’s no equivalent to R v. Jordan for kids in care. No hard deadlines to force the court to deal with child protection trials within a certain timeframe. No “stays” for families whose trials extend for years while kids bounce between foster placements.

I asked James whether he thinks the court should be beholden to a hard deadline for child protection trials. “I think there should be a deadline, but at the same time, I mean, if the parents aren’t doing the work, how can they expect to get their kids back within that timeframe?”

“I put in the work,” he says. “That’s why I got my kids home.”

Sam, the long-time family lawyer who works on contract with the MCFD, believes we’re unlikely to see an R. v Jordan equivalent for child protection cases anytime soon. Taking a case to the Supreme Court of Canada isn’t cheap. And most people caught up in the child welfare system are poor.

“Legal Aid doesn’t have the money to appeal on a constitutional issue of whether the court system’s taking too long,” says Sam. “Until someone has the money to take this to the Supreme Court of Canada to [get a ruling], like R v. Jordan, [which says] you have to complete ministry files to get kids out of foster care within a certain timeframe, there will not be that impetus.”

The Provincial Court is pledging to do what it can. In the latest annual report, Chief Judge Thomas Crabtree wrote, “Although factors like the number and complexity of new cases are beyond its control, the court continues to work to reduce times to trial.”

Former chief judge Ellan acknowledges that “the whole resource piece is a big problem,” but she thinks the problem runs deeper than that. “There is a systemic complacency,” she says, adding that every time a case gets delayed we’re sending an implicit message to families: “It doesn’t really matter that the struggling mother has to take the Greyhound bus to see them at the foster home. We’re not too concerned about that.”

Child protection trial delays are complex and we're still asking questions about them. Do you have a follow-up story idea? Email [email protected]

This piece was edited by Lindsay Sample with fact-checking and copy editing by Jon von Ofenheim. Dylan Cohen researched and wrote the explainer video which was shot and edited by Asher Isbrucker. The graphics and data interactive were created by Caitlin Havlak with research support from Diana Oproescu. Discourse Media's executive editor is Rachel Nixon.