How will the region’s growth impact transit?

Why the future of our transit system relies on more than just a 0.5 per cent sales tax increase

With contributions from Erin Millar, Josli Rockafella and Graeme Stewart-Wilson

Part 6

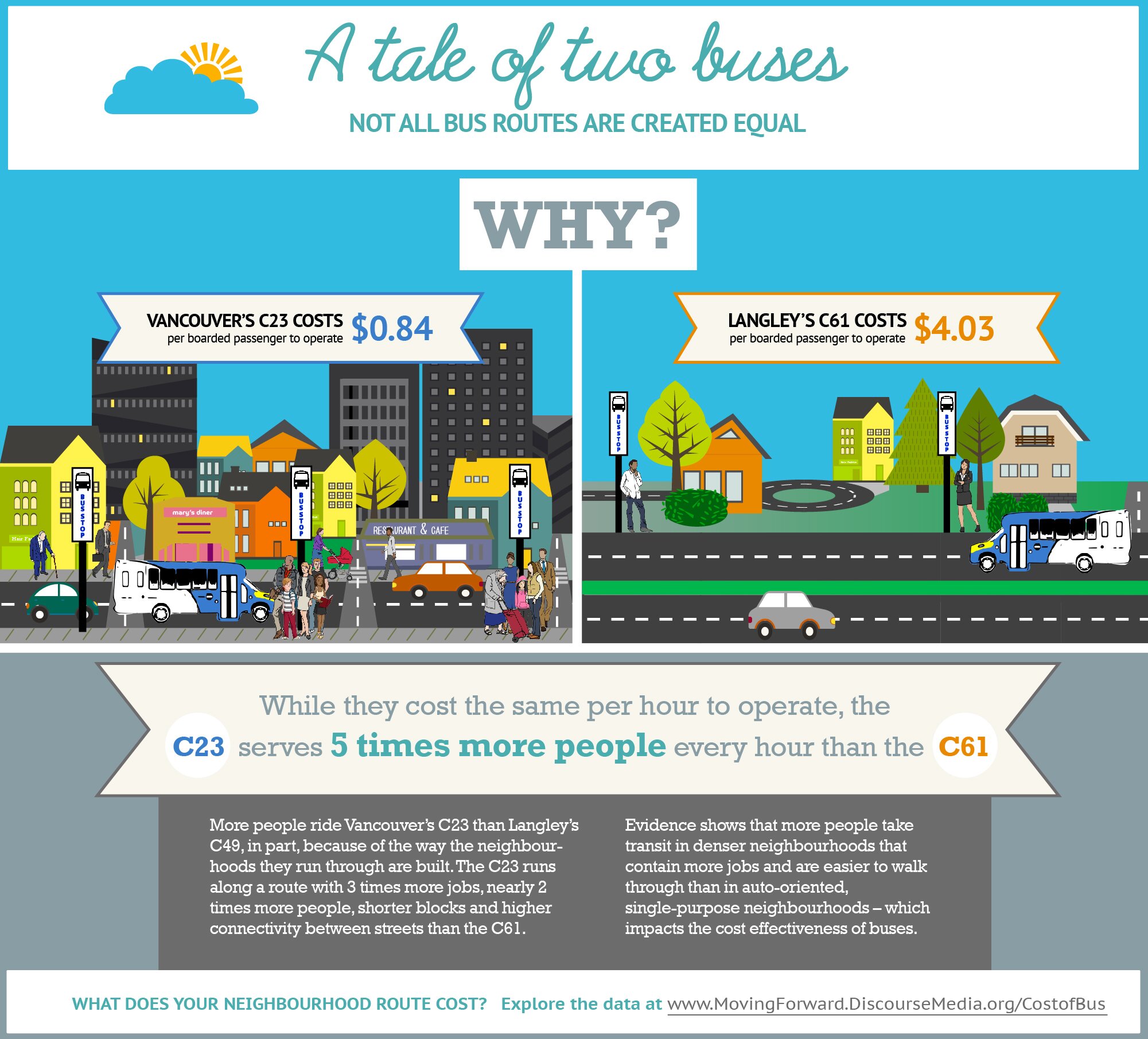

The C23 bus that putters along Vancouver’s downtown edge, travelling along Pacific Boulevard to English Bay, costs TransLink an average of $0.84 per passenger who steps on board. The C61, a similar community shuttle that winds from the Willowbrook Shopping Centre in Langley through streets that branch into the cul-de-sacs of several suburban subdivisions and back, costs $4.03 per passenger.

Why? Both buses cost the same to operate: about $61 per hour when you take operating costs such as the driver’s wage, fuel and maintenance into account. Where the two routes differ, however, is in the number of passengers they carry. The driver of the C23 in Vancouver sees an average of 72 passengers climb aboard each hour. The driver of the C61 in Langley sees only 15.

Mapping the cost per boarded passenger of all the bus routes in the region illustrates an often overlooked reality: some parts of the system, where bus routes cost less, overwhelmingly subsidize others. (See the bus cost calculator app at the bottom of this article to compare the cost per boarded passenger of any bus route in Metro Vancouver.)

We dug into the data to uncover what makes people more likely to take transit on some routes than others. What we found reveals that the factors that influence our travel habits get to the heart of how we design and build our cities. So how does the way we use our land impact the efficiency of our transit system?

How should Metro Vancouver pay for transit expansion?

Both the "yes" and "no" camps in the ongoing transit plebiscite in Metro Vancouver agree that transit expansion is necessary to accommodate growth in the region. For example, when West Vancouver mayor Michael Smith released a statement in January outlining his reasons for voting "no" in the upcoming referendum, he added that “the need for transit in our region is undoubted.” The crux of the disagreement between the two sides? How to pay for that expansion.

The "yes" side supports the proposed 0.5 per cent sales tax increase, arguing it is the “fairest” way to compensate for declining revenue sources like fuel tax and transit fares, which are currently not keeping pace with operational costs.

The proponents of a "no" vote have raised concerns about the increasing cost of running the system. The Canadian Taxpayers Federation, the official "no" side, accuses TransLink of a “stunningly bad record of waste,” asserting that TransLink could easily decrease spending by handing over the responsibilities of transit police to municipalities or by cutting executive salaries. They argue that a tax increase would result in further waste by TransLink.

We previously analyzed TransLink’s finances to better understand how the transit authority spends its money. That analysis found that the amount the organization spends on its entire corporate division in 2013, including financial and planning departments and management salaries, $91 million, accounts for seven per cent of its overall budget. Policing, at $31 million, accounts for two per cent.

So when considering TransLink’s efficiency, it is also relevant to look at the authority’s most expensive operational undertaking: buses. In 2010, TransLink’s bus division accounted for 50 per cent of the agency’s entire operations budget.

So why does it cost what it does to operate buses, and what does that tell us about the efficiency of the transit system?

Transportation costs are on the rise

The "no" side is correct in pointing out that, overall, operating Metro Vancouver’s transportation system has become more expensive. This is one of many conclusions drawn from an oft-cited 2012 audit of TransLink by Shirocca Consulting — a report commissioned by TransLink to assess its efficiency, a hoop it had to jump through before increasing fares beyond the legislated cap of two per cent annually.

So why did the cost of the system rise? For starters, between 2006 and 2010 TransLink expanded its service area faster than any other transit authority in Canada. The number of kilometres it serviced increased by 30 per cent and the number of paying riders rose by 28 per cent. Meanwhile, the population of the region grew by only eight per cent. This expansion cost $279 million, the equivalent of adding Calgary’s entire transit system to the Lower Mainland in the space of five years.

But the overall cost of operating the system increased more than could be accounted for solely by this growth. Case in point: the cost of operating an average TransLink vehicle for one hour grew by 21 per cent, from $108 in 2006 to $130 in 2010 — more than triple the rate of inflation. According to Shirocca’s audit, this can be explained, in part, by increases in hard costs like fuel and labour (the result of a new collective agreement) and other factors such as maintaining an oversized fleet.

However, that’s not the whole story. The fact that some bus routes are more expensive to run than others is relevant here. Much of the expansion of the system that took place over that time was in lower-density areas in the suburbs, where fewer people take transit, which means that TransLink cannot recover as many of its operating costs through fares as it does on routes that run through downtown Vancouver. As the auditors who wrote the Shirocca report put it: “The marginal cost of attracting new bus riders is high and increasing, in part because of expansion into lower density areas that are less transit supportive."

In other words, one reason transportation costs increased is because the system added service in the areas that cost the most to service — the suburbs. The more sprawling the region becomes, the more expensive transportation becomes. So, one way we could get more bang for our transportation buck would be to address the way our cities are designed and built as the region grows.

What is it about the design of a city that makes people more or less likely to take transit?

The connection between transit and development

When the driver of the C61 in Langley looks out the window, they see multi-lane roads branching into cul-de-sacs lined by wide single-story rancher homes with gracious yards and driveways. His colleague driving the C23 in the West End sees a grid of apartment buildings. While both environments are the result of conscious planning decisions, they have different impacts on the cost of providing transit.

Some of the reasons many more people take the C23 than the C61 can be explained by straightforward numbers. For example, 54,000 people live within 400 metres of the C23 route. Only 30,000 people live near the C61. There are 36,000 jobs near the C23 and only 11,500 in the vicinity of the C61.

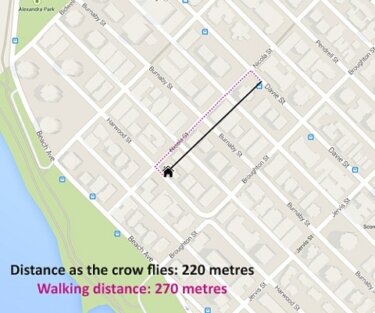

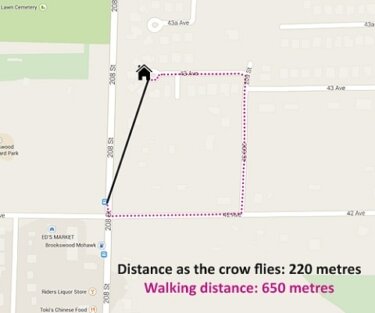

The design of neighbourhoods also influences people’s transportation choices. We are more likely to take transit if we can reach a stop within a short walk, rather than having to walk down a huge block to reach an intersection where we must cross many lanes of traffic. That’s why the intersection density of a place, measured in intersections per hectare, impacts transit ridership.

The expensive C61 Langley community bus runs through an area with about 0.18 intersections per hectare. The C23 runs through an area with an intersection density of 0.57 intersections per hectare. This measure is averaged over the entire route, but a snapshot of the route (seen in the graphic below) makes clear how this might impact your decision about whether or not to take the bus.

But this isn’t just an admonishment of the ‘burbs. One of the most interesting trends that emerges when examining the heat map that illustrates the cost-effectiveness of each route in Metro Vancouver is that nearly every city in the region has routes that are cost-effective and routes that are ineffective.

For example, the 321 between Surrey Centre and White Rock costs only $1.23 per boarded passenger. In Richmond, the 401 One Road/Garden City bus costs just $1.32 per boarded passenger — well below the $1.97 median cost of routes in the region, and about the same as the 33 between UBC and 29th Avenue SkyTrain station at $1.45.

That means that all areas of the region have the potential for cost-effectiveness. What efficient suburban routes have in common is that they run through parts of the city with higher population densities — residential populations greater than 30,000 — and high densities of intersections.

More expensive routes, on the other hand, are overwhelmingly found in neighbourhoods with low density and few local employment opportunities.

Of the 33 routes, not including night buses, that cost more than $3 per passenger to operate, only two operate inside of Vancouver. One is in Stanley Park and the other services Jericho Beach and UBC.

Since you’re probably wondering, the three most expensive routes in the region are: Ladner Ring’s 606 ($10.24), Maple Ridge’s C49 ($16.97) and the 259 to Horseshoe Bay/Lions Bay ($34.38). The three most cost-effective are the 231 from Lonsdale Quay and the 145 to SFU (both $0.69), and the 99 B-Line to UBC ($0.55).

So should we get rid of these expensive routes to trim costs? Not necessarily. But our local politicians should consider the cost of transit when deciding how to develop the region.

Transit as a social service

As with many public services, decisions are often made in spite of cost. Cost-effectiveness is by no account the only measure of the success of a transit system. The reason public transit is provided in areas that are expensive to service is linked to the awkward position of a transportation authority. TransLink is required to make financially prudent choices while meeting the economic and social needs of the region — a difficult dual mandate.

This tension is most obvious when considering night buses, which are among the most expensive routes in the system. The N15 route, which runs between downtown Vancouver and Marine Drive SkyTrain station from 1 a.m. to 4 a.m., costs $7.38 for each passenger that boards.

And yet, the Mayors Council’s plan to improve transportation promises to increase NightBus service by 80 per cent if the referendum is successful.

Why? Night buses provide a social service. While transit is often touted as a solution for congestion and environmental problems, it impacts society in other ways too. Advocacy groups, including Mothers Against Drunk Driving, consider nighttime public transit part of the solution to the problem of drunk driving. It also enables shift workers to get around.

(Note: while night buses have been included in the calculator app, they have been left off of the heat map, as their high costs are more a result of the time of service than of land use.)

Many people outside of the urban core rely on expensive suburban bus routes to reach their grocery store or doctor’s office. As Jarrett Walker, a Portland-based transportation planner who consults regions around the world, including Metro Vancouver, wrote in a response to the Shirocca report: “In reality, every transit agency runs service that has a purpose other than ridership.”

Walker goes on to note that transit agencies do this in order to equitably distribute service to all areas that contribute tax revenue to the agency (residents and businesses in these areas pay property taxes, fuel taxes and bridge tolls, contributing to TransLink’s revenue) and meet the urgent needs of small numbers of people living in areas that are expensive to serve (seniors, disabled people, those in isolated rural areas and so on). He offers a blistering critique of auditors like Shirocca that he claims “do citizens a great disservice” by implying that an agency should cut these services for the sake of cost-effectiveness. “In 20 years I have never encountered a public transit agency that actually deploys service exclusively for ridership,” he writes.

The bottom line

Following the same logic, the Mayors’ Council plan specifically notes the importance of basic service levels in low-density neighbourhoods. The plan calls for an additional 60,000 service hours in these areas, 14 per cent of the total service level increase in the proposal, stating that “in neighbourhoods with lower densities, where frequent service is not feasible, some basic level of service is still required to provide people with access to the rest of the transit system — in particular those people with few mobility options.”

But the reality is that fares make up a big part of TransLink’s revenue — nearly 40 per cent of overall transportation revenue.

Not every neighbourhood ought to look like the West End, but striking a balance is important if the region really wants to develop both a cost-efficient transportation system and a widely useful one as it grows. So the question is not necessarily whether or not it’s important to provide service to everyone. But the future of our transit system lies as much in the hands of local politicians who make decisions about land as in the outcome of the current referendum.