How does Metro Vancouver move?

On a typical weekday, the region’s residents make 6 million trips. Who is going where? What does that have to do with the transit plebiscite?

With contributions from Erin Millar and Josli Rockafella

Part 4

If Metro Vancouver citizens vote "yes" in the ongoing transit plebiscite, Vancouver will get a new subway along Broadway. Surrey and Langley will get a network of light rail lines. North Vancouver and West Vancouver will get new B-Lines. Richmond will get new SkyTrain cars on the Canada Line.

All of this, anyways, according to the typical media narrative, which focuses on what each city will receive for the proposed 0.5 per cent Provincial Sales Tax (PST) hike. But does it make sense to base our plebiscite vote on what the Mayors’ Council plan is promising to build in the community where we live?

The Mayors’ Council has pledged to decrease automobile travel in the region so that half of all trips are made by transit, bicycle or foot. We wanted to better understand whether or not the proposed plan will nudge the region towards that ambitious goal. But first we needed to take a deep look at where people travel in the region today and how they get there.

Unpacking data that describes how we move through Metro Vancouver reveals a picture of a complexly interconnected region, with people moving all over the place in different ways. Transportation systems are not made up of discrete pieces of infrastructure isolated in the city where they were built.

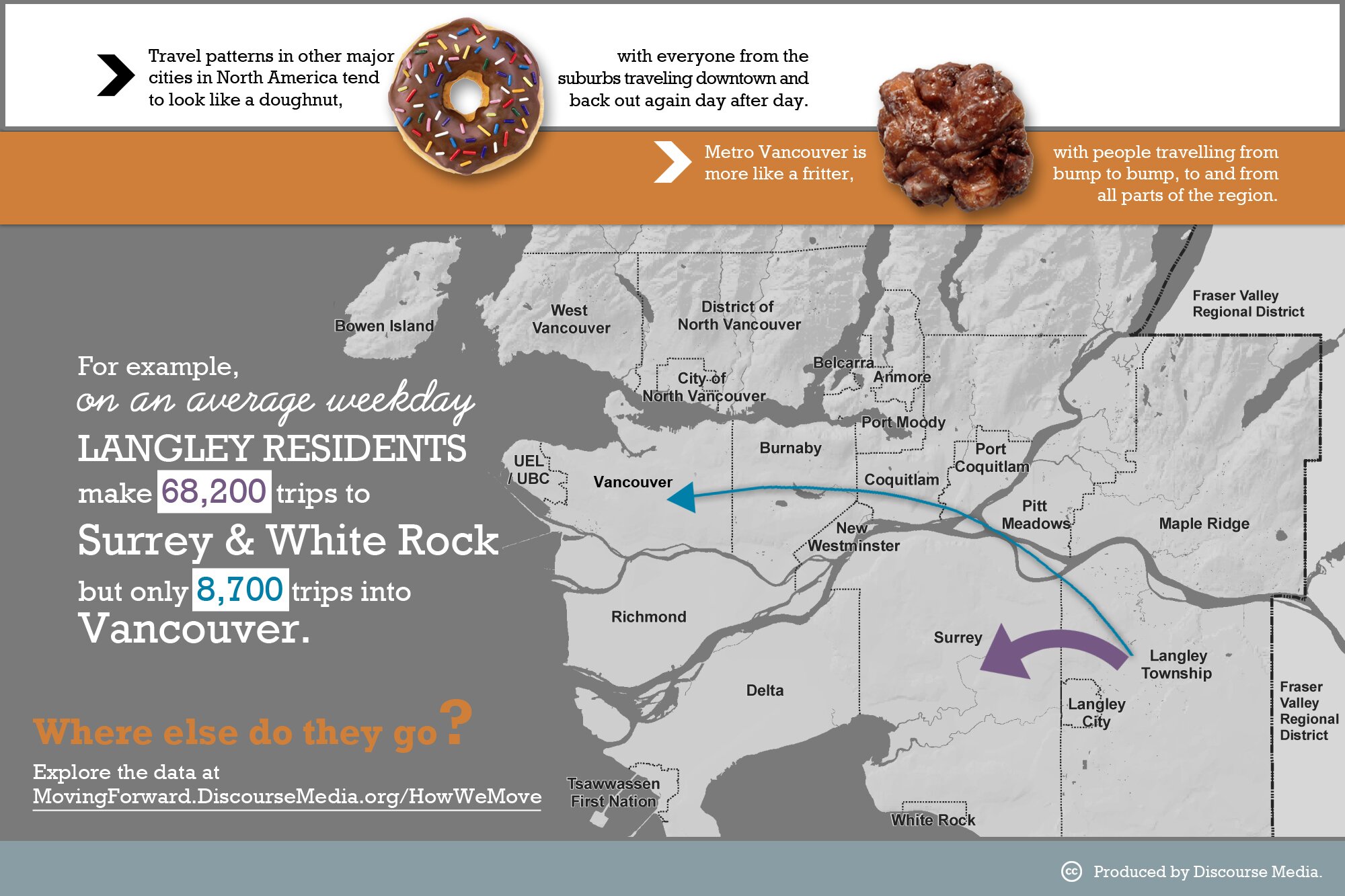

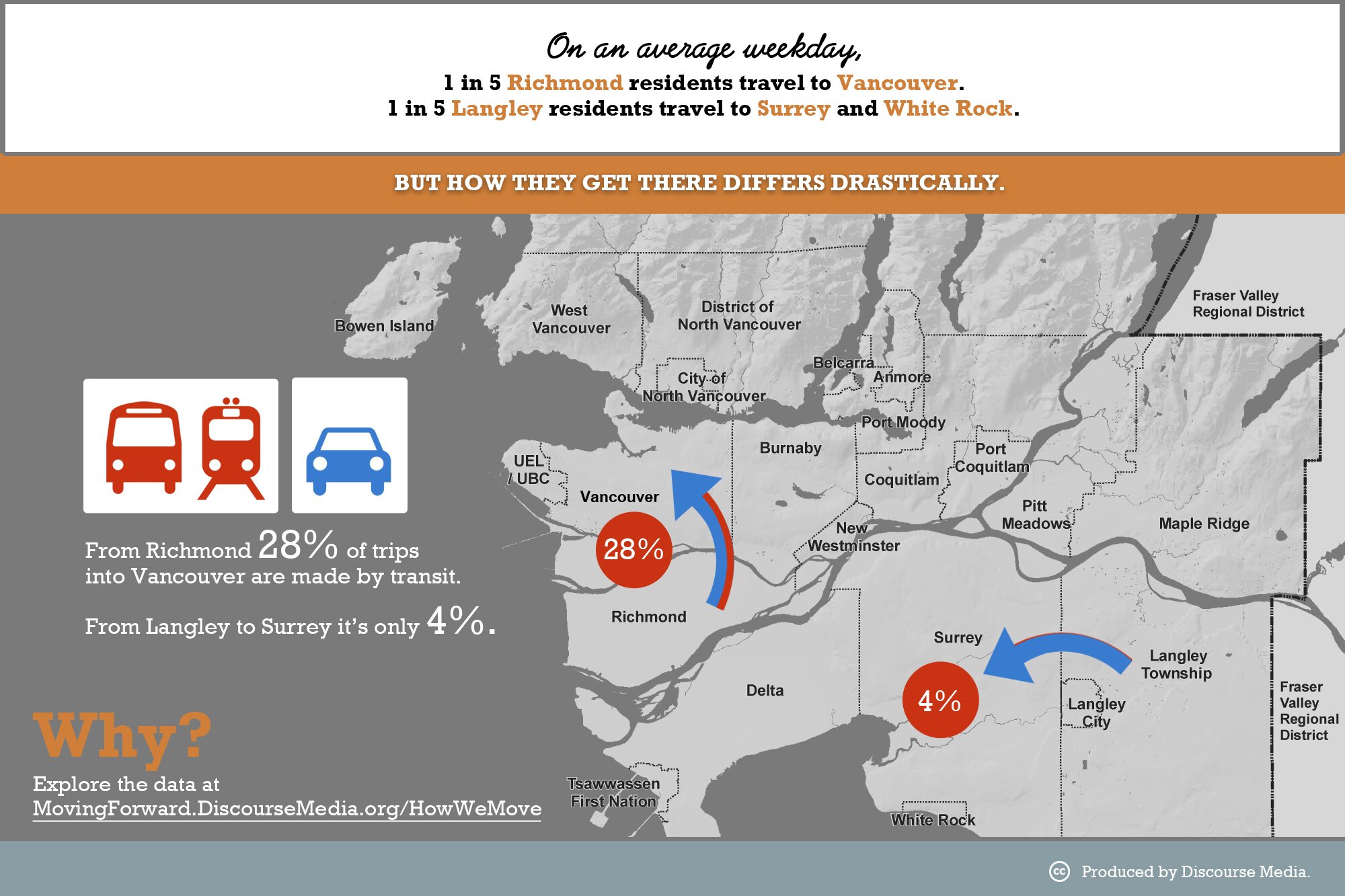

We found three important trends that are relevant to the referendum debate. First, our region doesn’t behave like most, where the primary direction of travel is from suburbs to city centre — a phenomenon transportation experts refer to as the urban “doughnut.” Also, we’re more likely use transit when travelling long distances than when only going a short distance. Lastly, the forms of transportation used by people in different parts of the region vary hugely.

We also learned that there are gaping holes in our current transit system. A more interesting question than "What does my city get?" is whether or not the proposed investments will fill these holes.

We are not a doughnut

Metro Vancouverites travel outside their home cities a lot. In fact, more than 30 per cent of all trips leave the areas or “sub-regions” they started in, according to the most recent Trip Diary Survey, a comprehensive report on travel patterns that TransLink publishes every three years.

(TransLink groups cities into sub-regions. For example, Burnaby and New Westminster make up one sub-region. The Northeast Sector sub-region includes Anmore, Belcarra, Port Moody, Coquitlam and Port Coquitlam. The full breakdown of all sub-regions follows the interactive below.)

Every weekday, for example, 37 per cent of people who start a trip in Langley City and Township head to other parts of the region. In some sub-regions, this pattern is even more pronounced. A whopping 44 per cent of residents of Burnaby and New Westminster leave their region each time they travel.

This in and of itself is not all that surprising. That people who live in a smaller city, like Burnaby, that lies next to a major city, like Vancouver, commute downtown seems pretty standard.

But that’s not the whole story. Interestingly, where we travel to and from is incredibly diverse.

Less than half of all people leaving Burnaby and New Westminster are bound for Vancouver. The majority of them are going to places like North Vancouver, Coquitlam, Surrey and even all the way to White Rock.

This commuting pattern is even more pronounced for cities further from Vancouver. On an average weekday, Langley residents only make 8,700 trips into Vancouver, but they make 68,200 trips to the South of the Fraser sub-region.

So, unlike typical North American cities, Metro Vancouver is not a doughnut, where everyone lives on the outskirts and travels to the centre. We’re more like an “urban fritter,” with lumps and bumps all over the place.

Transit works better for long distances than short

So how do our fritter-like travel patterns impact the Mayors’ Council’s efforts to decrease automobile travel?

Overall, Metro Vancouverites make 73 per cent of their trips by automobile. The data shows that we’re more likely to leave our cars behind when we’re travelling outside our own cities than when we’re running to the grocery store or visiting friends nearby. A quarter of all trips that end in a different sub-region from where they started are made by transit. When travelling for work, we only take our cars 66 per cent of the time. This is important because trips for work are almost twice as long as those for other purposes, so the impact of changing people’s commuting habits on overall kilometres travelled is significant.

But when it comes to moving within our cities, the car is still king. Take, for example, the North Shore. When people travel elsewhere, they take transit more than 25 per cent of the time. People take transit for 32 per cent of trips from the North Shore to Vancouver, and travel by foot or bicycle for an additional two per cent of trips.

But when travelling within the North Shore, only 18 per cent of trips are made by transit, walking and cycling combined. That means North Shore residents are almost twice as likely to take transit or ride their bikes to Vancouver than they are when picking up the kids from school.

This phenomenon can’t be explained away by the SeaBus to downtown Vancouver. North Vancouver residents are more likely to choose transit even when travelling to Richmond or Surrey than when moving in their own city.

Even in the City of Vancouver, with more plentiful and frequent transit options, 52 per cent of trips made within the city are by car.

There are huge differences in how we move in different parts of the region

But even for those longer trips between sub-regions, not all parts of Metro Vancouver are doing as well as others when it comes to getting people out of cars.

For example, about the same proportion of Langley residents travel to Surrey and White Rock each day as Richmond and South Delta residents who travel to Vancouver (one in five). 28 per cent of Richmond and South Delta residents travelling to Vancouver take transit, but Langley residents are almost certain to drive when heading to Surrey or White Rock; only four per cent take transit.

Other cities in the region are similarly diverse. As mentioned earlier, 32 per cent of trips from the North Shore to Vancouver are by transit. If, instead, you live in Maple Ridge and work in Coquitlam, you’ll only use transit six per cent of the time.

This analysis of our travel patterns reveals obvious holes in our transit network.

The Mayors’ Council plan proposes to plug some of these holes. For example, proposed light rail between Langley and Surrey and a new B-Line route between Maple Ridge and Coquitlam would increase transit options for the large number of people who travel between those sub-regions.

As we’ve seen, however, addressing how we travel for short trips within our cities will also be important if the region hopes to meet its goal. The Mayors’ Council plan includes significant investments to improve frequency of transit service on local routes. But will investments such as the promised 400 new buses be enough to increase frequency so that those buses are actually useful to people living in areas where transit is currently so infrequent? Also, people are more likely to replace driving with cycling and walking than with transit for short, local trips. So are the proposed infrastructure investments in the Mayors’ Council plan sufficient for people travelling by bicycle and foot? These are the questions we’ll dig into in future Moving Forward reports.

What’s clear is that it doesn’t make sense to base our vote on what the city we live in is set to get out of the proposed funding. Langley residents will feel the impact of light rail in Surrey. Many people from Burnaby will take the Broadway subway. Since our movements occur in an interconnected system, rather than being contained within isolated cities, we’ll all notice as our neighbours in North Vancouver or Coquitlam or Richmond change how they move.