Getting kids walking to school again with Safe Routes to School

The Doable City Reader

There is so much that can be done to make our cities happier, healthier and more prosperous places. Every day in cities around the world, citizens and city planners alike are showing us how small actions can scale up to have massive impact. And they can in your city too.

That’s what the Doable City Reader is about. In June 2014, 8 80 Cities, in collaboration with the Knight Foundation, brought 200 civic innovators from around North America together in Chicago at the Doable City Forum to share and discover methods for rapid change making. The Doable City Reader is inspired by the rich conversations amongst presenters and participants at that forum. It is a resource for any and all people who want to make change in their cities and is meant to educate, inspire and empower anyone to do so.

It’s no secret that children in North America are less active and more unhealthy than ever before. In the United States, childhood obesity has more than doubled in the past 30 years. Amongst adolescents it has tripled, leaping from 5 to 21 per cent. In 2012, more than one third of all American children and adolescents were overweight or obese. Similarly, in Canada, overweight and obesity amongst children and adolescents nearly doubled between 1978 and 2007, from 15 to 29 per cent. Since most adolescents do not outgrow this problem, and often continue to gain excess weight, it is estimated that up to 70 per cent of adults aged 40 years will be either obese or overweight by 2040 if current trends continue.

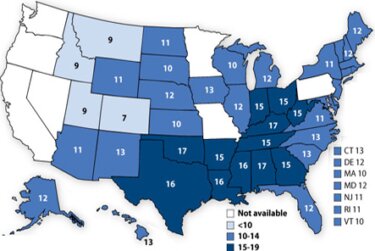

The factors compounding these statistics are many. But perhaps one of the most poignant is the steep decline in the number of children who walk to school. Screen time and unhealthy meals aside, if a child walks to school, as 48 per cent of children did in 1969, they are guaranteed at least some exercise five days a week for most of the year. With only 13 per cent of children and youth walking or biking to school today, it’s not surprising that the numbers correspond with skyrocketing obesity rates.

To tackle this trend, many communities in North America are finding ways to get their students walking to school again. A Safe Routes to School (SRTS) program gives schools, teachers and parents a toolkit to help them decipher and overcome barriers, which often revolve around safety. These programs usually include developing dedicated walking routes that are given infrastructural improvements and traffic calming to improve safety; chaperoned walking or biking “school buses” that pick children up at stops along the route; as well as outreach, education and incentive programs.

The results from these programs can be striking. Take Alpine Elementary School in Utah, for example. When the school began a SRTS program in 2008, only 35 per cent of Alpine students walked to school, even though 75 per cent lived close enough to walk. At the start of their program, the Alpine SRTS committee walked along the community’s dedicated routes to school (the state of Utah requires each school to create a neighbourhood access plan that identifies the safest routes for children to walk and bike to school) and noted safety issues that they worked with city engineers and planners to fix, including adding crosswalks, school zone signs, traffic calming and an off-road walking trail that led students to the back entrance of the school.

They created meaningful incentives: for every 10 miles that a student walked or biked, the school donated 40 cents to Alpine’s sister school in Kenya for a student lunch program (40 cents is enough to buy a week’s worth of lunches for one student), and the Alpine class with the most miles each month was treated to a lunch similar to what the Kenyan students were eating. The school also designated Walk to School Wednesdays, where students were given extra encouragement to partake. On one occasion the mascot of a nearby university walked with students. That day, 528 of the 555 students who lived within walking distance walked to school, plus many students who regularly took the bus. Only nine cars arrived at the school that morning.

And the results stuck. Many students who previously took the bus began walking regularly. Of the 555 students who live within walking distance of the school, 451 walked or biked to school for the month of September, more than double the number that did before the program. In total, students, faculty and staff walked 26,748 miles the first year of the program.

Other schools have seen similar results. Teachers at a school in El Paso, Texas that started a SRTS program in 2007 found that students partaking in the program had better test scores and behaviour on days they walked to school. Parents reported that their relationship with their children improved because they communicated more while they walked to school. A school in Windsor, Vt. saw a sudden 20 per cent decrease in morning traffic outside the school, making walking immediately safer and prompting a positive feedback loop.

The American Safe Routes to Schools website has an enormous number of resources for communities wishing to create a program for their school that can apply to any city in any country. These resources include parent surveys, tip sheets, evaluation cards and other documents that any school can print and use, as well as an extremely comprehensive guide to building and sustaining a program. It also has a portal for schools to track progress and submit and find data in their states, and numerous resources on how to access funding (local as well as federal — the federal government has specific programs that fund SRTS initiatives) in the United States.

The Canadian organization, Active and Safe Routes to School has a number of widely-applicable resources as well, including a comprehensive guide to ensuring children’s full and sincere engagement in the programs, webinars and downloadable PowerPoint presentations for giving to various stakeholders.