Police in Western Canada don’t collect, release racial data

We tried to find out whether police are racially profiling Indigenous people in cities like Regina. But police aren't required to collect data about suspects’ race or ethnic group, and some police departments refuse to participate in the FOI process.

One evening in December 2014, Simon Ash-Moccasin, an Indigenous playwright, actor and activist, was walking home through inner-city Regina when he was stopped by police officers. After refusing to tell them where he was going (“I didn’t have to tell him where I was going because I know my rights,” he later wrote), he was pushed against a wall, handcuffed and shoved face-first into a police cruiser only to be released soon after without charge.

The officers never read him his rights. He documented minor injuries in a doctor’s report the following day. Ash-Moccasin filed numerous complaints with the police department, police college and other public bodies, and wrote about his experience in Briarpatch Magazine.

“I felt like I was being harassed and that I was being racially profiled,” he wrote. “I’ve listened to countless similar stories about those same cops, and other cops too, that have gone against protocols.”

In an open letter published in May 2015 in response to community activists who raised concerns about police brutality, the Regina Police Service stated: “The Regina Police Service does not engage in racial or youth profiling although the Service maintains (as mandated) detailed records of incidents of reported crime and investigations.”

So, wherein lies the truth? Is Ash-Moccasin’s experience part of a larger trend of racially profiling Indigenous people in cities like Regina, as he believes? The answer is, we don’t know. And neither do the police.

These are the questions our team of reporters and data journalists at Discourse Media set out to investigate in September, in collaboration with Maclean’s associate editor Nancy Macdonald, who authored an explosive cover story calling Winnipeg the most racist city in Canada. While reporting in Regina and Winnipeg, we heard many anecdotal stories about similar police conduct — but were they isolated incidents?

Inspired in part by Toronto Star investigations and Desmond Cole’s Toronto Life story about the impact of “carding” on black Torontonians, we began investigating whether Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to be stopped or detained in Western Canadian cities. After consulting social scientists who have studied racial profiling, we asked police departments in Regina, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver to provide racial data related to public intoxication and drug possession — offences that are not consistently enforced, leaving enforcement up to the discretion of officers.

Many weeks later, we have no police data to help us understand what is happening on the streets in these cities — and little hope of ever obtaining any. Not one of the eight Freedom of Information (FOI) requests we sent turned up a viable source of data. The Edmonton police estimated that preparing the data would cost us $7,693, a figure out of the reach of our small journalism startup. (The Toronto Star obtained carding data from police after a years-long legal battle, a scenario that is increasingly less likely as fewer and fewer resources are available for investigative journalism.)

Sadly, our experience is all too common. A study published in the Canadian Journal of Law and Society shows police routinely suppress racial data when reporting annual crime reports to Ottawa. The research, led by Nipissing University assistant professor Paul Millar (who advised our investigation), calls the practice “whitewashing.” The few journalists who have succeeded in accessing data through the FOI process have waged lengthy and expensive battles.

So why is racial policing data so difficult to obtain when it is crucial for understanding whether police are treating minorities in an equitable way?

For one, police officers are not required to collect information about suspects’ race or ethnic group, and are therefore inconsistent in noting this information when they stop or detain an individual. This makes systematic data collection nearly impossible. Alberta, for example, does not collect any ethnicity-related information for public intoxication tickets. Ethnic information is noted in some cases of drug-related offences, but not all. Individuals’ criminal records kept at the Edmonton police department identify their race only 13 per cent of the time.

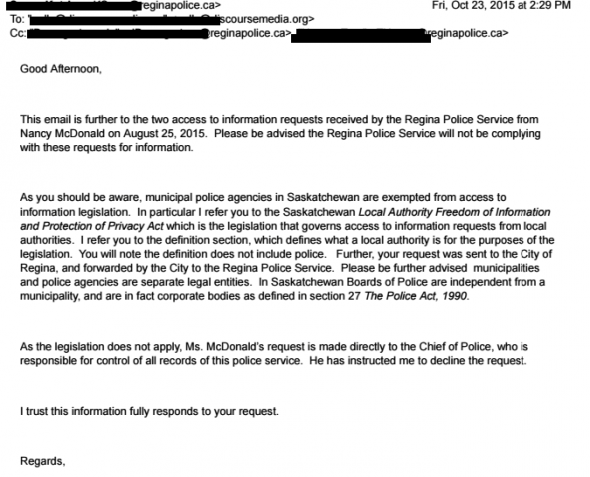

Other police departments refuse to participate in the FOI process altogether.

In a letter from the Regina Police Service in response to our FOI request, a legal counsel explained the service is exempted from the Saskatchewan Local Authority Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act because the definition of a “local authority” does not include police. In other words, the Chief of Police gets to decide whether to respond to an FOI request or not. He instructed the service to decline our request.

But why suppress this information? If police departments are serious about efforts to prevent or curb racial profiling, as the Regina Police Service argued in its statement, shouldn’t they track this information? At the very least, wouldn’t understanding as much as possible about who is engaged in criminal activity help police do their job?

A spokesperson for the Edmonton police department said racial data doesn’t significantly inform their policing work, and that they don’t see racial profiling as being an issue on their force. But how can a police department claim no racial profiling exists without data to show one way or another?

Even Statistics Canada can’t access reliable racial data from police. The agency gathers data to inform policymaking and community policing program planning. The Uniform Crime Reporting Survey has been collecting a crime census from over 1,200 separate police detachments since 1962, including criminal incidents, clearance status and information about the people involved, including Aboriginal status. We contacted the statistics department to access their available data, but we were told that the indicator of Aboriginal status is so inconsistently collected by police departments that it is effectively impossible to ensure an accurate count.

Despite the lack of reliable data, incidents like Ash-Moccasin’s are not unique to Regina. In September 2015, two First Nations chiefs in Edmonton decried racial profiling for undermining reconciliation efforts.

And yet, officials continue to dismiss allegations as isolated events.

“We would not presume to argue with the individual experiences and feelings of another person,” read Regina Police Chief Troy Hagen’s open letter to the community. “However, we also know these negative experiences make up a very small percentage of the total number of interactions we have with the public each year.” But do they really know? Journalists certainly can’t substantiate that claim.

This piece was originally published on CANADALAND. The findings of this investigation, based on surveys conducted by Discourse Media with the support of Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, were published in Nancy Macdonald’s investigation into the justice system for Maclean’s in February 2016.