Improving our media coverage of northern B.C. will take time

Reporter Trevor Jang reflects on an assignment that got personal.

I was climbing into a small speed boat off a dock in Prince Rupert when I heard a splash. I immediately patted my jacket pockets. Uh oh. It was my second day on the road and I had just dropped the Discourse Media company phone into the ocean.

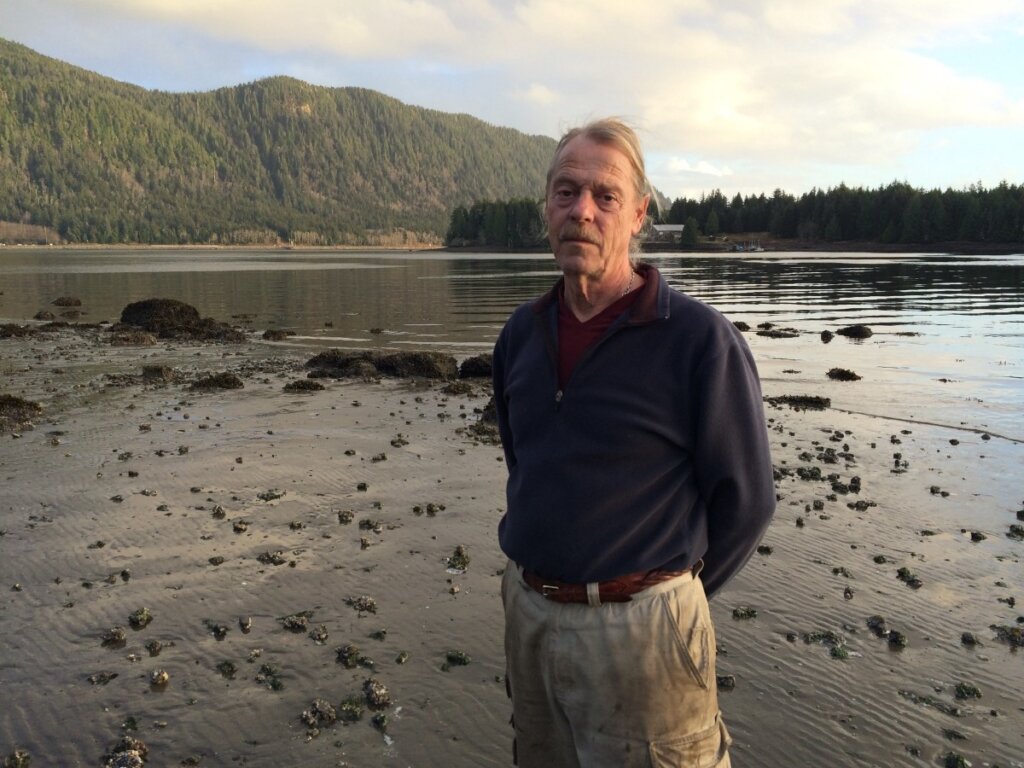

“You’re kidding me,” said Des Nobles.

“I can’t believe I just did that,” I replied.

“First rule of the ocean… always zip up your pockets,” said the retired commercial fisherman, laughing at me.

Des started up his boat and we ripped across the harbour. He was taking me to his home in Dodge Cove, a small unincorporated community on Digby Island. The proposed Aurora LNG export terminal could be built less than a kilometre away from the community. Residents are worried.

And I was rattled. It was a fitting start to an assignment that already felt strange and uncomfortable. I was in northwestern British Columbia for the next two and a half weeks, taking a Greyhound trip across Highway 16 from Prince Rupert to Smithers, to just listen to people. I hadn’t been assigned any story to tell. I had no angle to pursue. No deadline looming over me. All I had to do was meet people in these communities and hear them out. It seemed simple.

But it was a little awkward cold-calling people and telling them I wanted to meet to just listen and talk. It’s not something people are used to hearing from a reporter. People became open and receptive, though, after I explained that I was just looking to meet people in the community and find out what issues they cared about and what ideas they had for stories.

I set up casual coffee and dinner meetings. I planned to attend community events like the Pacific NorthWest LNG project update in Prince Rupert, the Economic Outlook Breakfast in Terrace and the Community Vitality Forum in Smithers.

I also started a Facebook group called “Improving our media coverage of northern B.C.” I updated it consistently with photos and short interactions from the trip. It was meant to engage the community and create a space for dialogue which could then fuel future stories. At Discourse, we want to use social media as a tool for community building and not just for pushing out our content.

But, honestly, I was worried about this group. I knew the LNG debate had divided communities. There’s a lot of animosity between those in favour of the industry and its promises of jobs and other benefits and those who worry about its impacts on the environment and Indigenous rights and culture. We were deliberately bringing all these perspectives into the group, and I wasn’t sure how it was all going to play out.

Listening to all sides

On the road I talked to people on all sides of the LNG debate who were feeling ignored. Residents of Dodge Cove voted 98 per cent against the Aurora LNG project. The terminal would be built a 15-minute walk from their doorsteps. It’s hard not to see that there would be impacts. But residents don’t think that means anything to the company or the government.

But people who support LNG development are feeling ignored too. I had dinner with some Prince Rupert residents who want to see the Pacific NorthWest LNG project move forward. A First Nations woman there, who was working for the company doing geological testing on Lelu Island, told me it was “incredibly frustrating” to have to go through the protesters on the island on a daily basis. People in her community have called her “greedy” and a “traitor” for working for the LNG industry. But, she says, she’s just providing for her family.

It seemed like this woman had been holding onto her story for a long time and was relieved to tell it. It made me wonder how often people get the chance to express their perspectives and personal challenges without immediately being ridiculed. I thanked her for sharing her story. I then tried my best to explain Discourse’s approach to journalism to her and the others at the dinner table.

Basically, I said, we want to include people in our story development process, rather than just having them consume the end result. This means opening up our editorial process in a somewhat uncomfortable way. But we hope that by collaborating with communities we can tell more in-depth stories. And when the time comes for me to tell this woman’s story, or another story that popped up at our meeting, the conversation won’t end once we press “publish.” We’ll keep following the story and keep listening.

Bringing two sides together in an unlikely way

When it comes to listening, we want to foster a place where other people listen to each other too. And, at least once, our Facebook group helped achieve this.

One post in the group started a back-and-forth between Shannon McPhail and Lucy Sager-Praught. Shannon runs the Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition and is loudly opposed to LNG. Lucy is an industry consultant who has organized pro-LNG rallies and has openly slammed folks like Shannon. “Some might think that you receive foreign funds to oppose local economic development. All I’ve ever heard is no. Any local economic development projects that your team has supported in the north?” she asked Shannon.

In the end the two decided it was best to meet face to face to discuss their differences rather than blasting everyone in the group with a Facebook notification every time one of them came up with a witty comeback. So they set up a coffee meeting in Terrace. I asked if I could tag along.

This had to be the absolute highlight of my trip. They both came into the meeting with open minds and open hearts. Lucy started by telling Shannon her story, telling her why she believes in the industry and sharing some of the hardship and ridicule she and her children have faced as a result of her being an industry advocate.

Shannon listened, gave her all the time and space she needed, and then responded. She told Lucy she’s not against all resource development. In fact, she’s trying to help start a mine that’s fully owned by the north, for the north. She’s interested in exploring renewable energy and fostering entrepreneurship in young people. These are things Lucy is interested in too.

And, as it turns out, they both love horseback riding. They set a date to go together. I caught up with Shannon again at her office in Hazelton the following week. By this point, Shannon told me, the two had become “soul sisters.”

“The way that the conversations have been happening in the north, you would think we’d tear each other apart. And it kind of started that way. But we reached out to each other and said that we both want good things for our watershed in the north, so let’s get together and make those things happen. We spend so much energy fighting each other when we could be spending a ton of energy working together to create the types of development that we could agree on,” she said.

The pair are now meeting regularly to discuss potential renewable energy projects and First Nations entrepreneurship training.

This experience made me realize that people are hungry to engage in respectful dialogue with those who have opposing views to theirs. But they lack opportunities to do so without the risk of being attacked, shamed or unfairly ridiculed for holding an opinion. Social media tends to make this problem worse. People either become segregated into echo chambers where they only see opinions they agree with, or they open themselves up to “trolls” and comment wars.

That was what I was trying to avoid in our Facebook group. So far the group is succeeding, but our biggest accomplishment was not simply creating dialogue online. It was acting as a bridge for two people to meet face to face. It’s only one example, but it’s a start.

Moving forward with engaging the north

Though I got a lot of positive interest and feedback, not everyone agrees with what we’re doing. Some people are upset we couldn’t visit their community. I apologize for that. I wish I could have visited every community. Some people think we haven’t improved our media coverage of the north at all. They’re right. We haven’t yet. But I’ve built a network I can turn to when a story idea pops up. It’s the beginning of a process for building deeper community reporting.

This will take time. It will take more visits, more phone calls, more moderated Facebook discussion and more listening. I feel as if I’ve learned so much, but also nothing. Mostly, I’ve learned that I’m going to have to keep learning if I want to help improve media coverage of northern B.C.

For me, this is personal. I came to Discourse for two reasons. The first was to escape the daily news cycle and have the time and freedom to slow down, explore complex topics and engage people in depth. The second was that I’d get to serve northern B.C. I don’t want to create the impression that I’m just another “big-city reporter” who doesn’t really care about the north. The issues that impact the north impact me too.

I ended my trip exploring homelessness in Smithers. The people who are homeless in Smithers are mostly Indigenous, and they all hang out together at Bovill Square, a public square and outdoor stage at the end of the town’s quaint main street. The homeless shelter is two doors down from the stage.

The group is drunk on a near-daily basis and they spend their time panhandling to be able to afford the next bottle (which they all chip in for and share). Earlier this year, the “Smithers Confessions” Facebook page displayed outrage from community members in posts about the “drunk Indians” or “dirty Indians” harassing families walking by Bovill Square. The page has since been taken down.

I approached the group one day and told them a little about myself. I told them I was Wet’suwet’en and my mom was from Moricetown, the reserve just outside Smithers.

“Which family?” they asked.

“David,” I replied.

“Who is Peter David to you?” one of them asked.

“Uncle,” I said.

“Holy shit, we’re cousins!” he said, laughing.

I always knew I had a lot of long-lost cousins scattered about — the fallout of belonging to the generation that came after residential school and the ’60s Scoop. But I didn’t know I had cousins who were homeless. That broke my heart. And I’m still frustrated because I don’t know what I can do about it, other than continue telling stories that include a range of perspectives and hold people in positions of power accountable.

This experience reminded me of something else Shannon said. She posted it on Facebook after our coffee with Lucy.

The north is a different place. We are a bunch of small communities where our personal, cultural and professional lives are not separate. Talking about development has been a very unsafe conversation lately. We believe debate is important but only when it’s healthy and respectful. We will always work hard to protect our watershed from ill-advised development…not because of the land and the rivers, but because of the people who call it home.

It’s true that I’m based in Vancouver, and that’s not as effective as reporting for the community, in the community. But I’m still Wet’suwet’en. I’m still culturally, spiritually and socially tied to the north. And I hope I can keep experimenting with journalistic theories that may make a difference in at least a few people’s lives each time I visit.

I’m still listening. And I’ll be back again. Home is always home.