Violence against women in Canada: We have national data, and we’re sharing it

Explore the rates of police-reported violence against women in more than 600 Canadian communities and help us fill in the gaps.

After news broke in October that dozens of women had accused Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual abuse, more and more women have come forward to share their own experiences with sexual violence. #MeToo shows that for women, assault and harassment is unfortunately the norm — not the exception.

But just how prevalent is violence against women? That’s a complicated question that I’ve been trying to answer.

Statistics Canada does track police-reported data on violence against women but detailed national data isn’t easily available to the public. So Discourse requested a custom dataset documenting police-reported rates of violence against women in Canada from 2008-2015.

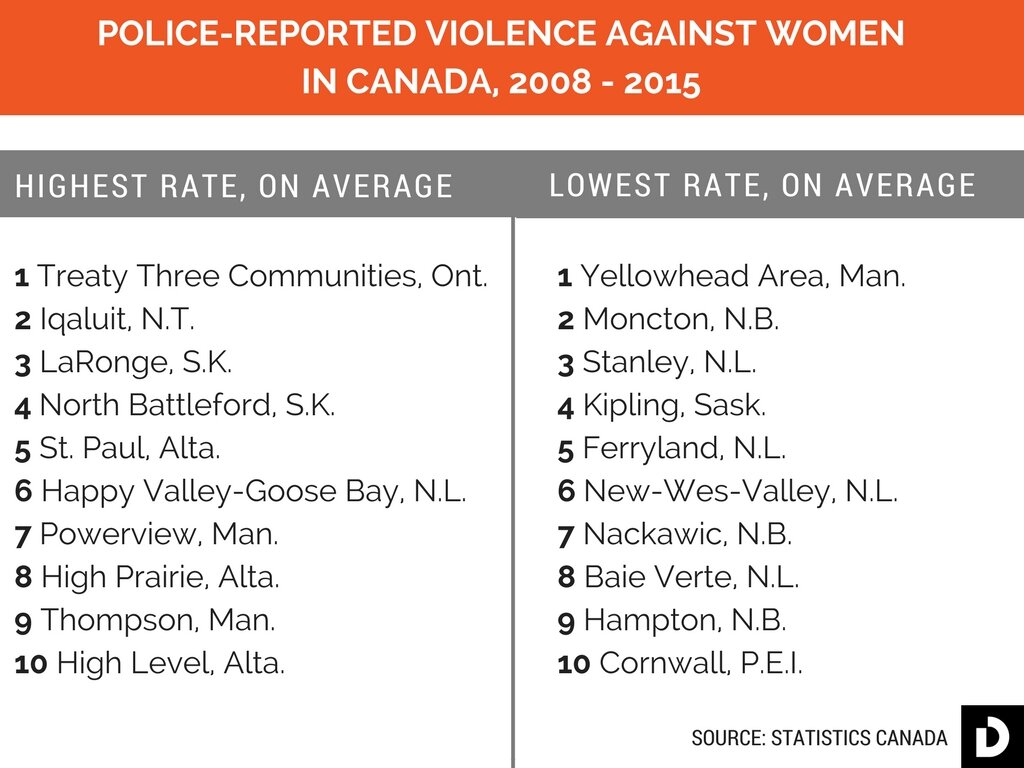

It took months, but we now have the dataset, which includes more than 600 communities. It shows that the national average of police-reported violence against women appears to be going down slightly, with 1113.9 reports acts of violence per every 100,000 people in 2015. But the real trends that underpin the data are much more nuanced.

Each community has many stories that we can’t tackle alone. We’ve created an interactive tool that allows you to select from more than 600 communities, to learn about their rates of police-reported violence over time and compare them to the national average.

If you’re a journalist, we hope you can use the tool to spark a story about your community. What stories does it tell? And perhaps more importantly, what perspectives or trends are missing? Share your stories using the hashtag #cdnviolencedata and let’s talk.

If you live in a community with a particularly high or low rate of violence, I’d love to hear what this data means to you. Does it resonate with your experiences where you live, or not? What does it bring up for you? Tweet us using the hashtag #cdnviolencedata or reach me at .

Police-reported data ‘only a fraction’ of the story

It’s important to know that police-reported data, especially about violence against women, is a controversial unit of measure. Consuming the data responsibly means being aware of its limitations.

Jane Stinson, the principal investigator and director of the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women’s FemNorthNet project, says it can be challenging to know how to interpret the data. For communities where the rates of police-reported violence against women change dramatically between years, Stinson wonders, “is that due to a change in policing [or] a change in violent behaviour?”

Bryan Kinney, associate director of undergraduate programs in SFU’s Department of Criminology, has been part of a number of projects involving data on gendered violence in the past decade. He says that police data doesn't paint a full picture of what's happening to women.

“Roughly maybe half to a third of everything that happens gets reported to police. Maybe a third again get to the next stage. Maybe a third again, and so on,” he says. “So by the time you get to the actual incidences of founded or confirmed cases, you’re really talking about a slim slice of the pie.”

Violence is everywhere, Kinney adds. “It happens in workplaces, in universities, in government, it certainly happens in the private sector.”

There are many reasons victims would not report the violence they experience. Sexual assault, a common form of gendered violence, is one of the most underreported crimes in the country. According to Statistics Canada, this is due to “shame, guilt and stigma of sexual victimization, the normalization of inappropriate or unwanted sexual behaviour, and the perception that sexual violence does not warrant reporting.”

“Many women experiencing sexual and domestic violence, especially those marginalized by discrimination in society, continue to face barriers to reaching out for help and also reporting to police,” explained the Ending Violence Association of British Columbia, a provincial nonprofit organization that works to coordinate and support community-based anti-violence programs across B.C., in an email.

Stinson says it’s very difficult to understand the causes of very high or very low rates of police-reported violence “without knowing more about each [community] and the local factors.” She notes, however, that many of the communities with the highest rates of police-reported violence have significant Indigenous populations, adding “this may partly be explained by colonization as one of the root causes of high rates of violence experienced by Indigenous women and men."

Publishing this data is a starting point for conversations about violence against women in Canadian communities. If you live in a community home to some of Canada’s highest or lowest rates of police-reported violence against women and you would like to share your story, reach out at .

The data interactive for this piece was created by Caitlin Havlak with data entry and fact-checking by Emma Jones and Jon von Offenheim. The story was edited by Lindsay Sample. Discourse's executive editor is Rachel Nixon.

If you would like to use this data please use the following credit at the end of your piece: "The police-reported sexual violence data featured in this story was originally obtained by Discourse Media.”

For more coverage related to sexual violence in marginalized communities, click here.

Correction: a previous version of this story described EVA BC as a nonprofit providing counselling and outreach programs for victims of violence. EVA BC does not provide programs but coordinates and supports community-based anti-violence programs across B.C. (January 11, 2018)