Why journalists need to listen to communities

I like to think of Discourse Media as a laboratory in which to experiment with new ways of doing journalism to improve reporting on solutions. Over the past year, we’ve learned a lot from these experiments. What would happen if we embedded two journalists at a gathering of civic innovators? (The Doable City Reader.) Could we create independent journalism while working directly with a client sponsoring our content? (The Spirit of Discovery.) How could we tell a story about schools all over the world working together to improve schools? (Deeper Than Knowledge.)

The thread that ties all these projects together is collaboration. We’ve partnered in new ways (new for us, anyways) with funders, sources and media organizations. But one group we haven’t yet found a way to partner with in a meaningful way is our audience. How can we better engage regular people and communities in our reporting at every stage?

So when I was introduced to Andrew Haeg, entrepreneur-in-residence at the Center for Collaborative Journalism, I felt like I had hit the jackpot. Andrew is founder of Groundsource, a new digital engagement tool for journalists and researchers designed to capture communities’ voices (particularly underrepresented ones).

In a piece published on Medium, Andrew explains: “We need to create a place that affords privacy but retains accountability. One that’s for more than just venting — a place to communicate problems and observations with an expectation of being heard. This could be the platform for a new journalism based on trusted values. … [We] need to connect the view from the ground with the view from above to tell true, human stories in context.”

Andrew’s words resonated with me because if my goal was to produce journalism that contributes to positive change by telling stories about solutions, I better understand the problems from a normal person’s perspective. I needed a better way of listening to communities’ stories, hopes, frustrations, vision, needs, questions and so on. Too often we journalists listen only to the typical sources (experts and leaders) or the loudest community members. For example, when reporting on school change, it’s easy to seek out the perspective of the teachers’ union or the education minister or the most pissed-off parent. But what about normal kids and parents? What about regular teachers? Can Groundsource seed a virtual network that is to me, the education journalist, what the police station is to the crime reporter?

Groundsource intersects with the concept of the “listening post”, developed by NPR’s VP of diversity in the early 2000s and it is all about creating a place (whether physical or virtual) where community members express their voice and are treated by journalists as a legitimate news media source.

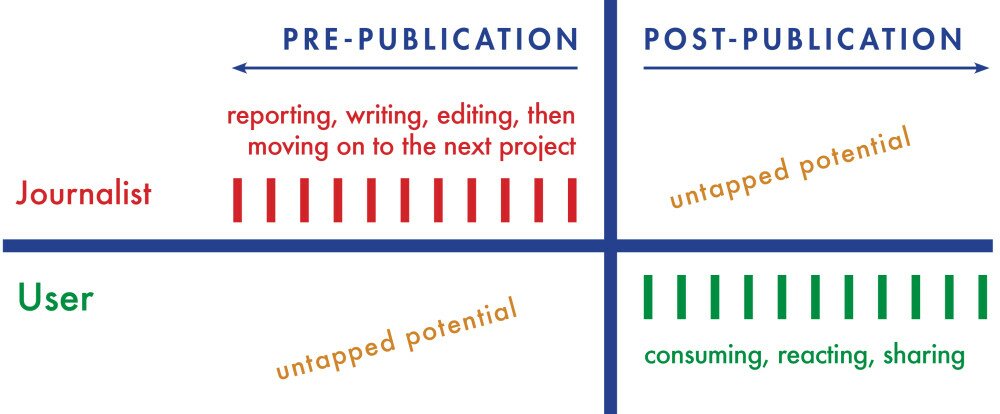

The aim is to shift the flow of information between community members and journalists. The traditional “broadcast model” involves journalists gathering information from the typical sources that already have authority (or the loudest community voices) then publishing the work and moving on to the next project while the community of readers then read, share and debate the product in isolation from the journalist — so, primarily one-way communication. I believe that we journalists ought to make better use of the expertise of community members’ lived experience. I see promise in a model that engages community members in shaping reporting pre-publication and builds a meaningful relationship between journalist and community post-publication. The above diagram (developed by Meg Pickard) captures this concept nicely.

Over the next few months, we’ll be exploring ways to apply these concepts to our journalism − and cooking up some new experiments in the lab. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a quote from this article about WBEZ’s Curious City journalism project in Chicago: “When we [journalists] build with our communities we build space for more people to shape our stories and cultivate a sense of ownership over the process. This shifts to locus of journalists’ authority from the act of publishing to the process of engaging. It makes journalism more accountable and more valuable.”