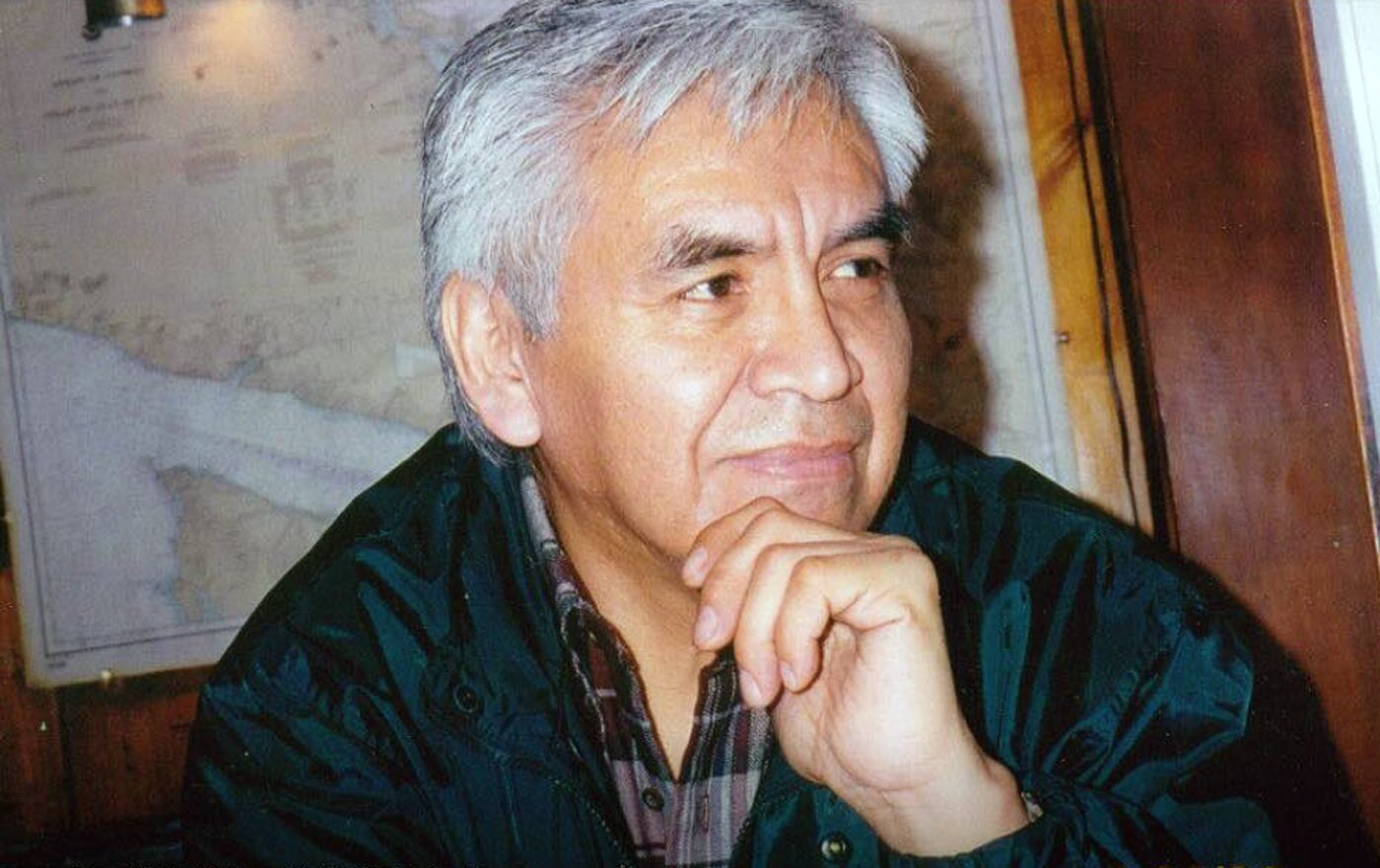

Remembering Larry Guno: B.C.'s forgotten Indigenous politician

The late MLA fought for Indigenous rights during a very hostile time for First Nations people in British Columbia — and he’s still influencing a new generation of Indigenous politicians.

During the 1960s in northern B.C., jobs were aplenty and life was good.

Prince Rupert was a bustling town, especially during commercial fishing season. And Terrace was a busy hub where loggers and miners could be found mingling with businessmen in the town’s watering holes.

For Indigenous people, though, something else was just as common: racism. Some quietly endured racial slights and ambled on with life. For others, racism burned like being branded with a hot iron. It instilled a conviction that sparked action, so no one else would have to live with the same indignity.

Larry Guno, the late Nisga'a MLA for Atlin who died in 2005, embodied the latter. In the ‘60s, he and his brother-in-law were travelling together through northern B.C. by car. Tired from the long drive, they stopped at a hotel to get a room for the night, but were refused accommodation. "The owner said he doesn't serve First Nations people," recalls Larry’s younger brother Don Guno, 64. “Indian people were discriminated against in a thousand different ways back then. You never felt like you belonged anywhere. I think it took a lot of self-confidence to overcome that.”

This incident and others compelled Larry to act. He sued the hotel owner because what happened wasn’t right and it had to be made right. “He saw injustices that were happening with Indigenous people all around him, and he wanted to help change that in some way,” Don tells me from his apartment in Vancouver, where photos of Larry sit on a shelf in his living room.

"You never felt like you belonged anywhere. I think it took a lot of self-confidence to overcome that."

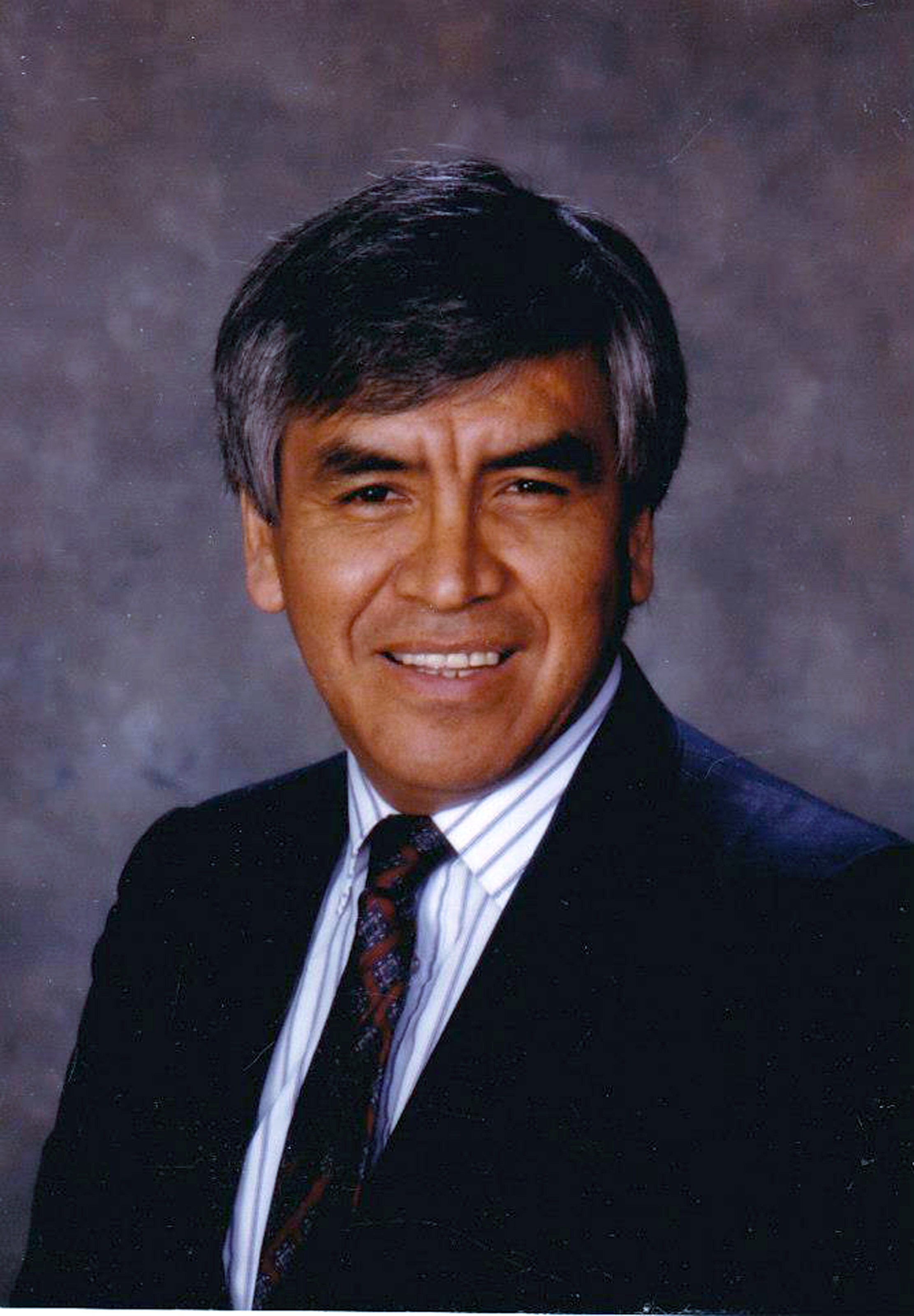

But Larry’s quest for justice didn’t stop there. He earned a law degree from UBC in the early ‘80s, and fought for Indigenous people in court. Then in 1986, after seeing how B.C.’s legislature in Victoria made decisions that influenced Indigenous lives without their input, he ran for provincial office in the northern riding of Atlin — and won. Larry became only the second First Nations person in B.C. history to be elected as an MLA. (The first Indigenous MLA, Frank Calder, was also Nisga’a and also won in Atlin in 1949.)

At age 46, Larry’s victory was the capstone on a life whose youth was steeped in confidence-corroding discrimination that made a successful political career unlikely.

Tough beginnings

Born in 1940, Larry grew up in the Nisga’a village of Old Aiyansh, a long way from B.C.’s legislature in Victoria. In his preteens, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and spent the next two years in the Nanaimo Indian Hospital, 1,500 kilometres away from home. Larry’s parents worked seasonally and couldn’t afford to visit him. The facility was like a sterile tomb, but it was also the anvil on which Larry’s fortitude was hammered. "He told me how lonely he was. He never forgot that, and I think it had a big effect on him for the rest of his life,” Don says, alluding to Larry’s struggle with the traumatic effects of that experience and his time at residential school. “But he also told me that when he got older, he felt like he could do anything because he'd gone through all that when he was young. I thought about that when he ran for MLA.”

After the Indian hospital, Larry spent four years at the Edmonton Indian Residential School. And as a young child before that, he watched racist federal fisheries officers demean his father’s First Nations heritage, while fining him for trivial infractions. Then there was the hotel incident.

“Those things really lit a fire in Larry. He said our people shouldn’t suffer being treated like that,” says Don. “He felt that our people were shunted to the side and forgotten. His whole idea was to get out there and be heard — that was what he wanted to do.”

Larry lived in Prince Rupert after leaving residential school around 1958 and worked in a mill. Later in his life, he moved to Vancouver to attend UBC, and worked as a lawyer before becoming the MLA for Atlin.

But upon his arrival in Victoria, Larry encountered not only a government hostile to Indigenous rights, but also open racism. He found that wanting to change Indigenous policy and legislation — and trying to do so once inside the seat of provincial power — were two very different things.

The lone Indigenous MLA

Former Alberni MLA Gerard Jannsen, a fellow NDP member, roomed with Larry in Victoria. Jannsen says Indigenous issues weren’t on the political agenda of the then-governing Social Credit Party. “The political climate then was awful when it came to First Nations people. They believed First Nations peoples had no aboriginal rights and no land rights,” he tells me.

With no apparent political recourse to advocate for themselves, Indigenous people took to the streets. Protests flared in Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island), Clayoquot Sound and Pemberton. Jannsen says Larry saw these flashpoints as part of a bigger picture: “Larry used to say in our caucus meetings that these weren’t just isolated issues, that there was a whole series of issues linked across the province that had to be addressed.”

In a 1991 interview with the Indigenous newspaper Windspeaker, Larry noticed that First Nations people were developing a collective consciousness and preparing to fight for themselves. "[Indigenous Manitoba NDP MLA] Elijah Harper and his lone stand on Meech [Lake Accord] gave our people a sense of 'Hey, we can challenge their moral authority and win,'" he told the Canadian paper. “We're not so powerless as we used to think."

Although Larry found some sympathy in the NDP caucus for Indigenous issues, he faced racism at worst, and haughty disinterest at best, from the rest of B.C.’s legislature.

He faced racism at worst, and haughty disinterest at best, from the rest of B.C.’s legislature.

Jannsen recalls a racist comment made by former Social Credit highways minister Neil Vant during one legislative session that prompted a swift response from Larry. “Vant made a statement in the house that he was tired of highways looking as dirty as Indian reserves,” he tells me. “Well, Larry really felt that, and he tore a strip off of Vant when he responded. Went up one side of him and down the other.”

Disillusioned after one particularly frustrating legislative session, Larry headed home to spend time with family. On a drive from Prince Rupert to New Aiyansh with Don, he confided his frustrations with being an Indigenous MLA. “He talked about speeches he tried to make about Indigenous issues in the legislature and how other MLAs would get up and walk out. He said it was like they didn't care about anything he had to say," Don tells me. “Being an Indigenous politician in a white man’s government was about as far away as you can get.”

Larry felt being an MLA didn’t give him much opportunity to advance the kind of change he’d hoped to make, Don says, and that Ottawa was where the real levers of power were. “He saw he could do more and have a bigger voice if he was an MP, that he could command more attention to Aboriginal issues, and speak out against things that were happening,” he tells me. “That's why he tried to run for MP later [in Skeena in 2000], but he lost.” Larry ran for the federal NDP, placing third with 6,273 votes. He came behind Liberal Rhoda Witherly, who placed second with 8,714 votes, and the Progressive Alliance’s Andy Burton who won with 12,787 votes.

Paving the way

Today, in this age of truth and reconciliation, there's a new generation of Indigenous MLAs. In this year’s B.C. election, Carole James (NDP), Melanie Mark (NDP), Adam Olsen (Green Party) and Ellis Ross (Liberal Party) won in their respective ridings. But, although the sitting Liberal government may no longer be publicly hostile towards Indigenous MLAs, they still face some of the same barriers from Larry’s time — obstacles that never really went away.

His diplomatic example was among the factors that inspired James and Mark to run for MLA. James, who knew Larry personally, ran for and won the BC NDP leadership in 2003. Meanwhile, Mark, who knew of Larry, won a Vancouver seat for the first time last year. Both say they’ve dealt with some of the roadblocks Larry did in trying to change Indigenous policy and legislation.

James remembers Larry from her days as coordinator of the now-defunct Northern Aboriginal Authority for Families, which he chaired. “At that time, I wasn't looking at provincial politics. But after heading that way, I thought often of Larry and what it must have been like,” James, who is Métis, tells me. “I just can't imagine how challenging it must have been to ... [be] an Indigenous MLA in that kind of environment, surrounded by people who encouraged a lack of recognition of Indigenous rights in this province.”

"He showed that the human spirit can thrive even in the most adverse conditions."

In B.C.’s current legislature, James says many MLAs remain ignorant about Indigenous issues, and that the government is reluctant to prioritize them. This lack of understanding is apparent during Question Period; questions about Indigenous issues are automatically referred to the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation — whether it’s a health, highways or education issue, she explains (I contacted the ministry to verify this, and it didn’t immediately respond to my request for comment). During the throne speech that opens legislative sessions, Indigenous leaders are brought in, and recognition of traditional territory is made, but James says that’s not enough. “It’s not part of the day-to-day routines for everything in the legislature,” she tells me. “While [Indigenizing the throne speech] seems small to some people, I think it's an example of the importance of acknowledging Indigenous issues. There's been progress, but we have a long way to go.”

For her part, Mark cites reconciliation as an example of how the struggle for Indigenous issues is almost as difficult today as it was in Larry’s time. She says she’s been to ceremonies where the government uses a talking stick (the holder of this Indigenous ceremonial wooden stick has the sole right to speak while others present must listen), and mentions collaborating with Indigenous people. It all looks good — that is, until Mark tries to bring up any issues.

“The minute I speak truth to power, the majority [Liberal] MLAs will laugh and heckle, and make comments that I find are completely hypocritical of their policies,” she tells me. “These are people that are supposed to be leaders that represent all people. But seeing them in action shows me another side of how far we have to go yet.”

Later years

Larry didn’t run for MLA again in the 1991 provincial election, in which the NDP swept to power. But politics never left him. He was operating his own consultancy when, in 1998, he helped Nisga’a officials with the final leg of negotiations for the Nisga’a treaty with Canada and British Columbia. Specifically, Larry wrote the Nisga’a Lisims Government Administrative Decisions Review Act, which holds the Nisga’a government accountable through an independent board of directors that reviews its decisions.

Officials said Larry was instrumental in the agreement’s wording, Don tells me. "They didn’t want a non-Nisga’a lawyer doing this. They knew he was the only one who could write in the same language that government negotiators did, and who could interpret things our leaders didn't understand,” he says. “We didn’t find out about this until after Larry died. He never talked about it. That's just the way he was — he never bragged about the things that he did.”

Despite his involvement with tribal politics, Larry never ran for tribal office because of what he saw as their destructive nature. “He said tribal politics could be vicious, cutting and personal, and that it was less about politics and more about power, prestige and money in a small place,” Don explains. “He said you couldn’t get anything constructive done in that kind of environment.”

After his failed shot at becoming an MP, and having penned the Nisga’a final agreement, Larry yearned to write something very different — something non-political — Don tells me.

He started documenting his time at the Edmonton Indian Residential School, and used theatre to tell his story. The result? A final draft of a 2005 play titled Bunk #7. Larry’s story and characters were modeled after his own tight-knit group of friends who, finding themselves hundreds of miles away from their families, formed a family of their own in the crushing vacuum of residential school.

“He wanted people to have a better understanding of what residential school was about in a time when residential school was just starting to become news,” Don says. “He showed that the human spirit can thrive even in the most adverse conditions.”

One excerpt from a program listing Bunk #7 captures how the loneliness of one character was fed by the rich memories of a distant home: “Oh God, at this moment, we are all thinking of home, of our families, of the places that we miss. We thank you for all the beautiful things like the sea, the sound of the breakers rolling in, the call of the raven, the quiet murmur of the rivers, the sound of the voices of our forefathers from the forest, and most of all, God, the mountains and all our relations.”

In the early 2000s, Larry sought the guidance of Marianne Weston, coordinator of the Terrace Little Theatre Society. She connected him to Indigenous playwright Yvette Nolan, who in 2003, helped get Larry’s play workshopped by the Native Earth theatre collective. Larry finished his final draft in June 2005, as it was slated to debut in Toronto the next year, but he never got to see it through. Larry died, age 65, in his home on July 17, 2005. He was buried in his First Nation of New Aiyansh, where he hadn’t returned since leaving residential school.

Ultimately, Bunk #7 didn’t debut in Toronto. A staged reading was given instead, with some of the Guno family present. Playwright Michael Armstrong finished the script, adding excerpts from Larry’s private notes. Since then, it’s lived on in readings given to at-risk youth, residential school survivors and Indigenous communities. It was also part of a 2014 Truth and Reconciliation Commission event in Edmonton.

“Things like this came to be after he passed away. It makes me sad that it happened after he passed away,” Don tells me. “I think he did his part, though, writing that play about [a] residential school.”

Larry Guno may be gone now, but he continues to quietly influence a new generation of Indigenous leaders through his work with the Nisga’a treaty and Bunk #7. One thing that hasn’t changed since his tenure as an MLA 30 years ago? The day-to-day struggle to advance Indigenous issues beyond cultural ceremony, and beyond braying about them during legislative sessions. Larry defended and sought justice for Indigenous people during an era when belittling them was once the norm. He didn’t just leave a legacy. He left an obligation.

Video by: Anya Zoledziowski