Why a northern Canadian community's hopes for the future rest on one power line

Stung by a legacy of colonialism, residential schools and teenage suicide, off-grid Pikangikum’s energy solution could be a single 90 kilometre-long transmission line

CANADA

- Population: 35.16 million people

- Electrification rate: 100.00%

- Renewable energy consumption: 20.60%

- Access to non-solid fuel: 100.00%

Source: World Bank

PIKANGIKUM, ONTARIO — Sitting in his chair, socked feet firmly planted on the cold floor, Gordon Peters, the usually animated former Chief of Pikangikum, froze and stared expressionlessly out his office window.

Outside, snowmobiles zipped across snow-covered Pikangikum Lake, one of thousands in the region gouged by retreating glaciers during the last Ice Age; trucks rumbled up and down the ice road that connects the community to the outside world in the winter; and kids with skates and hockey sticks slung over their shoulders crunched through the snow to a cleared patch of ice.

Peters did not move. His eyes watered; he began to slightly shake, but quickly steeled himself.

Peter Quill, another former Chief of this remote fly-in aboriginal reserve located about 1,400 kilometres northwest of Toronto, stepped in to answer. The question was about one of the key recommendations in a government report on 16 youth suicides in two years in this community of about 3,000: getting hooked up to the provincial electrical grid.

The veins of the provincial electrical grid don’t quite reach the community, requiring Pikangikum to rely on an aging generator system that runs on diesel flown, trucked or shipped into the area at great economic and environmental cost. It’s the same situation with 22 other remote First Nations reserves across the Canadian province of Ontario (two others have diesel generators as a back-up to wind or hydro).

To make matters worse, the reserve’s 18-year-old main generator, currently past its 10-year expected life span, recently broke down in early February. Rene Keeper, a die-hard Green Bay Packers fan who takes care of the diesel generators on behalf of the Eshkotay Wayab Power Authority, said a new one can hopefully be flown in within a couple of weeks. Until then the community will have to resort to timed blackouts, switching every two hours between homes on the east and west side. Councilor Don Quill often hears from families during blackouts: “They complain they can’t cook food for their kids to eat.”

Longer-term, the maxed-out energy system has prevented Pikangikum from making many of the infrastructure improvements its community members sorely need. Eighty per cent of Pikangikum’s homes do not have wastewater systems or running water. Its housing supply has tightened into a crisis, as the population grows by 100 people each year with little prospect for new builds. As many as 16 residents might share a small home, requiring some families to sleep in shifts.

“Their ability to evolve and develop is curtailed by the fact they don’t have this necessary resource,” said Bert Lauwers, lead author of the The Office of the Chief Coroner’s Death Review of the Youth Suicides at the Pikangikum First Nation 2006-2008, and Deputy Chief Coroner of Ontario at the time it was released in 2011. “Having a good source of electricity is integral to having improved quality in their lives.”

"Having a good source of electricity is integral to having improved quality in their lives."

As the population continues to grow, maxed-out generators age and blackouts roll through the community, there is hope in the form of discussions with a First Nations-owned transmission company. Uncertain at this point, some in Pikangikum are optimistic. Others remain wary of past promises. Pikangikum was once told a grid connection would be coming “pretty soon,” said Keeper. That was 18 years ago. “Eighteen years is not ‘pretty soon’ to me.”

“If you had 3,000 people living near Toronto and they didn’t have electricity, what would happen?” asked Gordon Peters. “They’d get electricity within a year, months even.”

Energy affects everything else

The first time Kurt MacRae visited the home of a student at Eenchokay Birchstick School, where he serves as principal, he said he almost cried. Nine children, two teenage parents and two grandparents were sharing its tiny quarters. The children were huddled around an old electric stove, the wide-open oven door providing a source of heat.

“Kids go to school because they’re trying to survive,” he said, whether it’s to evade alcoholic parents and grandparents, to access food and clean water, and/or to escape their often cramped living conditions. “They’re not getting the right amount of sleep and it’s really not creating success as they transition from the home into the school.”

Pikangikum currently has about 450 homes and requires at least 200 more to address their housing crisis, which will continue to deepen as the population grows. Even if Pikangikum were able to build 200 new homes, they wouldn’t have the electricity to power them. As Keeper from the local power authority explained, there can be “no more hook-ups”: the current diesel energy system is unable to provide electricity for any new homes to be connected.

“Young couples are still living with their parents and they are starting families,” Deputy Chief Jonah Strang said in a council chamber meeting earlier this February. “They need their own place.”

Boil water advisories are a constant in the community, and the majority of its homes do not have running water or indoor toilets. Six water stations are scattered throughout the town, often at a great distance, requiring families to use outhouses and haul sleds with buckets to fetch water for drinking, cooking and bathing their children. In the winter, this becomes a daily hardship in temperatures as low as -40 C.

“When there is a power outage, which could last anywhere from five minutes to five hours, they have no stove to boil the water to make it safe,” said Sylvain Langlois, a Métis worker with the Pikangikum Health Authority. This escalates the problem of energy access into a health concern. Families in Pikangikum primarily use formula to feed their babies, said Langlois, and during outages they may take risks by mixing it with unsafe water.

"When there is a power outage, which could last anywhere from five minutes to five hours, they have no stove to boil the water to make it safe."

In 2014, the Pikangikum Working Group, a team of volunteers created after the Coroner’s report was released in 2011, installed 10 running water systems in the most underserved homes in Pikangikum with approximately US$225,000 in private donations, the largest by the Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund. The group was set to install another 10, but during a conference call with then-Deputy Chief Dean Owen, the plans were scuttled. The maxed-out power system couldn’t handle the additional load of the water heaters and pumps.

Bob White, a Toronto-based engineer and member of the Kitpu First Nations who led the initiative, said the initial plan was to have the federal government match funds, but the government backed out. “They said they didn’t have the money,” White recalled. The federal government did, however, invest approximately US$35,000 to train Pikangikum workers for the project.

WHY DO YOU CARE ABOUT ENERGY SOLUTIONS?

Tell us why these stories matter and what you’ll do with this information.

So close to the grid... but so far

Nearly 17 years ago, Pikangikum came close to being connected to the power grid that has eluded the community for so long. “They were on the precipice of moving into the modern era,” said Deputy Chief Coroner Lauwers in a recent interview. In 1999, a power line from Red Lake to Pikangikum received approval from Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), the department responsible for meeting the Government of Canada’s obligations and commitments to Indigenous people. Within a year it was 35 per cent complete, with 40 km of hydro poles put up, when federal funding for the project was abruptly halted. What happened, according to the band’s former lawyer Doug Keshen, is a “classic ‘he said, she said’ scenario.”

In November of 2000, INAC notified the Pikangikum Band Council that they would be taking over management of the council and its finances due to a series of calamities. These included flooding at the water treatment plant, a fuel oil spill at the school and alleged financial mismanagement. Chief and council refused to concede management and sued then-INAC Minister Robert Nault, who currently serves as the federally-elected representative for Pikangikum’s area. This set off a decade-long court battle against Nault, during which time many infrastructure projects — including the power grid connection, water and sewer projects — were shelved. Pikangikum later lost the suit in 2010.

In his ruling for the case, Justice John dePencier Wright wrote that “to this day, the power grid has not been completed. Power that could have been supplied at a cost of several hundreds of thousands of dollars continues to be supplied to this Band at a cost of millions of dollars.”

Energy from diesel is exorbitantly expensive compared to energy from the grid: court documents from the 2010 case state that Pikangikum paid over US$3.4 million for power from diesel in one year, which would have cost nearly a tenth of the price if supplied from the provincial grid.

These annual savings, had the grid been connected back in the early 2000s, could have been either funneled back into the community or used to pay for the project itself.

Energy permeates education

Aboriginals are the fastest-growing population in Canada, with almost half under the age of 25. In Pikangikum, according to Deputy Chief Strang, between 60 and 70 per cent of its population is under the age of 25. While the impact of a power grid on the future of a youth population might seem a tenuous connection in other parts of the province, here it is sorely felt.

For example, energy permeates education. “In the past, every five-year cycle, we would lose the equivalent of a full school year due to closures,” school principal MacRae said shortly after underscoring how important school attendance is. Power outages, he said, are a major factor for the closures.

A recent US$50-million rebuild of Eenchokay Birchstick school — a massive source of optimism and pride in the community, which has its own diesel generator — will help ease overcrowding issues, but will require more teachers. But MacRae is concerned about retaining the teachers he has, let alone recruiting more.

“Some teachers won’t return because of the inconsistent power,” he said. The majority of Pikangikum’s residents have wood-fired furnaces to heat their homes, but teacher residences rely solely on electricity for heating. Power can be down for minutes, to hours, to several days, forcing teachers to either evacuate or hunker down on their couches, as MacRae himself has experienced, huddled in layers of clothing until the power comes back on.

In addition to prolonged outages, power surges (a sudden spike in the electrical current) and brownouts (a sudden dip in the current), have destroyed thousands of dollars worth of laptops and audio-visual equipment.

For a school that has gone underfunded (per-pupil spending in band-operated schools has historically been lower than that of provincially funded ones) and in an era where educational technology is touted as a surefire path to student success, MacRae has been forced to get creative from time to time.

"If students lose connection to the school, their risk [of suicide] exponentially goes up."

While driving to Eenchokay Birchstick, MacRae also relays a particularly grim, but honest, insight. “If students lose connection to the school, their risk [of suicide] exponentially goes up.”

A teacher’s job description in Pikangikum likely wouldn’t match a counterpart’s in Southern Ontario. “We spend a lot of time on mental health issues,” said MacRae. “I think 30 per cent of our time at the end of the school year is actually focused on prevention and getting kids help.”

MacRae recently called Northern Store, the reserve’s sole shopping centre, to get pencil sharpeners and razors off the shelves and behind the counter; students were using them to cut themselves. In the second week of February, MacRae was at the nursing station “probably every day” with a different student. One student downed an entire bottle of Tylenol before school and was cutting herself in class. MacRae managed to get her to his office and called the nursing station. She was slashing at her wrists with the zipper from her jacket while in his office. She was later “medevacked” (medically evacuated) out to nearby Sioux Lookout.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

Recently there have been rumblings that a grid connection is not far off. Both provincial and federal Liberal governments have committed to spending billions on infrastructure and tackling climate change. (Getting a number of remote northern communities in Ontario off diesel would not only substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also reduce the risk of spills.)

In 2014 the Independent Electricity System Operator, the agency responsible for planning Ontario’s transmission lines, released a report that made the economic case for connecting 21 of the 25 remote First Nations communities in Ontario, which would result in approximately US$900 million in savings over 40 years. The following year, the Canadian provinces and territories of Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland/Labrador, Northwest Territories, Yukon and Ontario governments created a Pan-Canadian Task Force to reduce the use of diesel fuel to generate electricity in remote communities.

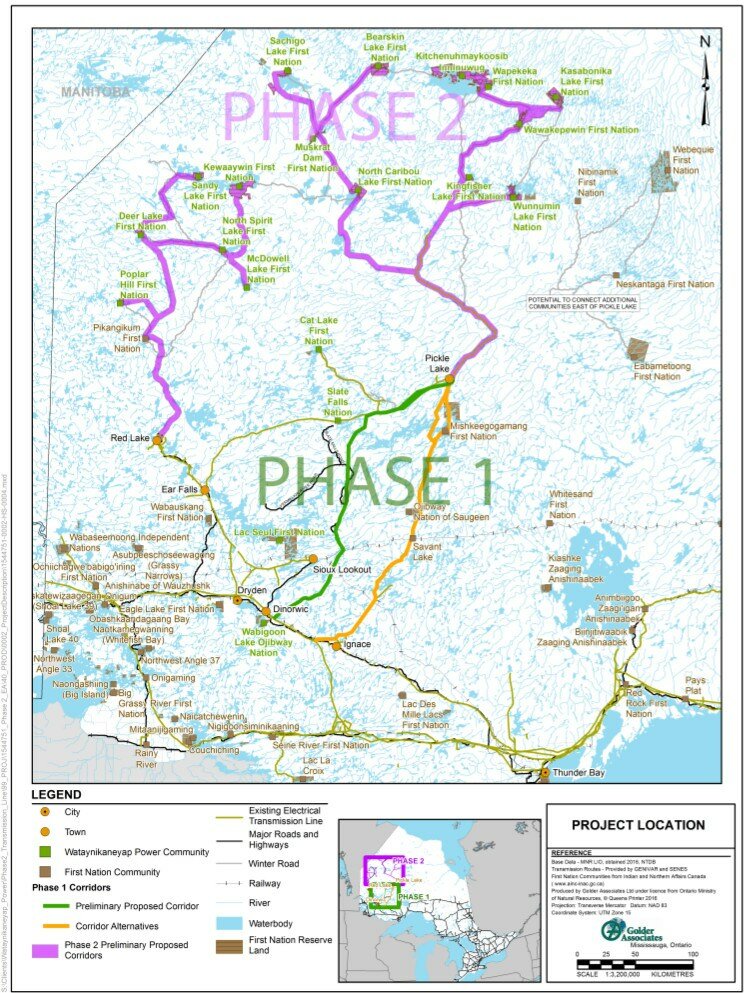

Most recently, Pikangikum has entered into discussions with a First Nations energy group, Wataynikaneyap Power, which is working on a US$1.03-billion, 1,500-km transmission project that will connect 16 First Nation communities in northwestern Ontario. The communities involved will be majority owners of the transmission facilities, and over time, will retain full ownership of the systems. PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates the project will create 769 jobs and almost $900 million in social value.

Phase one of the Watay Power project, which will add capacity to an existing transmission line to Pickle Lake, 265 km east of Pikangikum, is planned to be completed by 2018. Phase two, which will run through Pikangikum, is slated for completion in 2024. That is a long time to wait for a grid connection that is fewer than 100 km away in Red Lake, which explains why Pikangikum was initially reticent to sign on to the project. There are suggestions from both Deputy Chief Strang and Pikangikum generator manager Keeper that this timeline may be shortened. The timelines are subject to ongoing discussions between Pikangikum and Watay Power.

But for now, Pikangikum continues to wait.

Energy Access and Youth

Once Pikangikum’s youth leave school (dropping out is the most likely route), the prospects for employment are low. The reserve’s unemployment rate is 90 per cent, and likely higher for youth. But a connection to the grid would be a boon for economic development and provide young adults with job opportunities. According to a 2013 report prepared by Lumos Energy for the Wataynikaneyap Power Project, a grid connection would spur both public and private economic development including construction and operating jobs, skills development and establishment of job qualifications and experience.

The Pikangikum Working Group’s water installations in 2014 had precisely that effect on a number of youth involved. For one particular young man, learning how to install running water “changed the way he carried himself,” said Colleen Estes, a Christian minister who has worked in the community for almost two decades. “His self-esteem went up.”

“Why would I want to move?”

In the office overlooking Pikangikum Lake, former Chief Peter Quill waved off the question about the Coroner’s report and its recommendation for a grid connection. Two of his own grandchildren were mentioned in the report. He described all of the problems in their house — problems that a grid connection would not solve.

“Maybe it’s because we’ve been assimilated to another culture…we use this [English] language and it kills us as a person, it kills the spiritual part.”

Energy alone will not solve Pikangikum’s problems: it is not a magic bullet. It is not a guarantor of a healthy and vibrant Pikangikum. What it can do is offer opportunity, a platform for a community to grow and flourish, as opposed to a tether that binds and limits.

“It goes back to the very issue of colonization of First Nations people by Euro-Canadians, and their isolation in remote reserves,” said Lauwers, lead author of the coroner’s report. He said the Pikangikum people feel a deep kinship, ownership and attachment to their land. “And what happens is they stay there, and don’t get education, don’t get skills, and live in abject poverty.”

By Peters’s own estimate, 98 per cent of Pikangikum residents never choose to live anywhere else.

“Why would I want to move? This is where I was born, this is where I will probably pass on, this is where my mother and father were born, this is where they are buried. This is my home.”